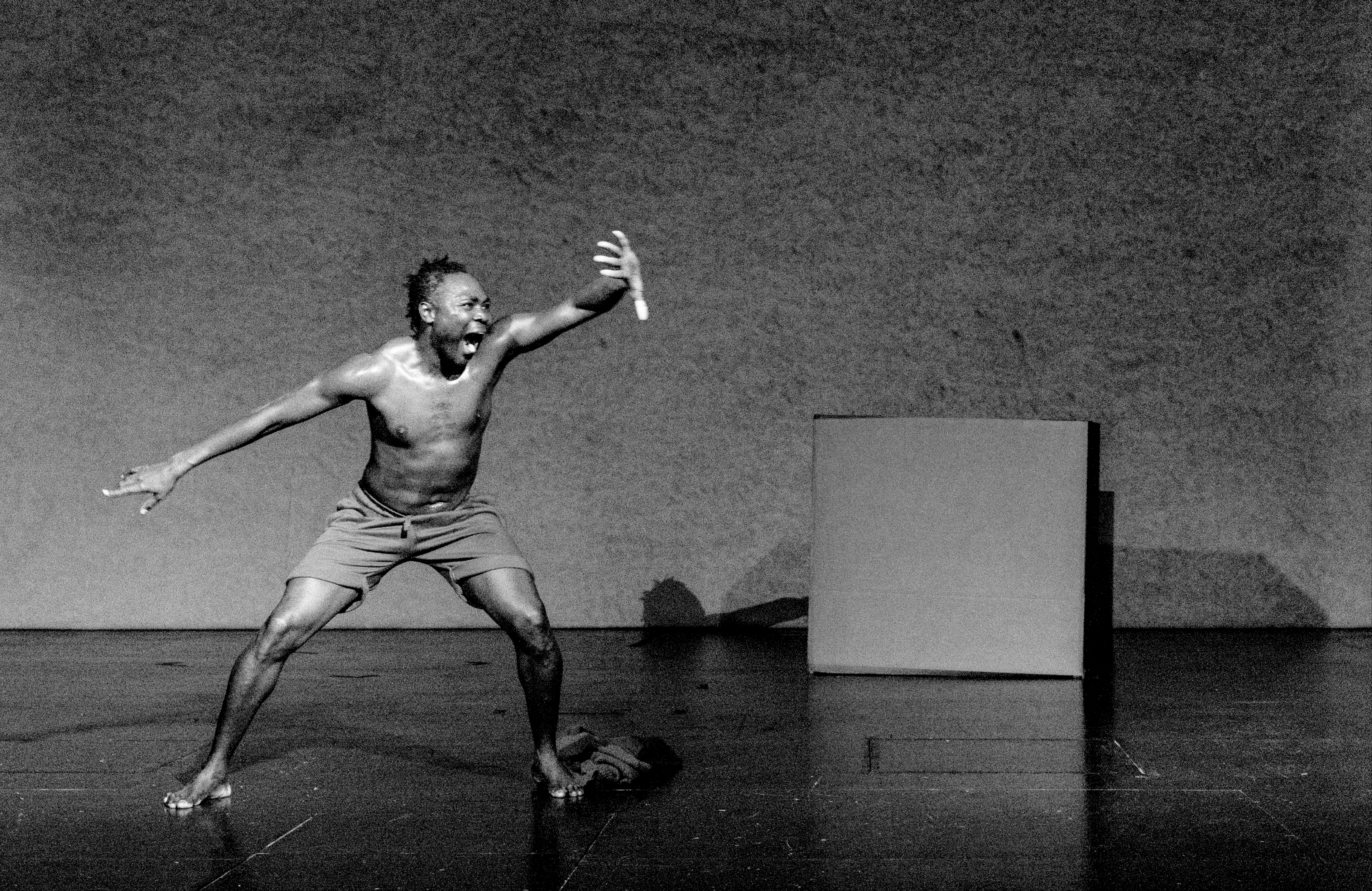

Taigué Ahmed

Dancer

Chad

Early in his career, Taigué Ahmed–a world-renowned choreographer, dancer, and cultural activist from Chad–had a realization that would change his life and his work: Movement could be a salvation, a remedy for even the most enduring of traumas.

As a young child in the south of Chad, in the village of his birth, Taigué remembers the day that members of a rebel group came into town, trapping people in their homes and setting them alight. Men and boys in particular were targeted. To survive this attack, his family had to disguise him as a girl.

Years later, Taigué speaks from his home in Paris. He paints a picture of the forces that alimented his creativity, and the events that led to his exile.

“Dance, for me, is a very effective weapon for liberation, for liberating the body.”

As quotidian violence spread throughout his community, Taigue’s family decided that it was time to move to Chad’s capital, N’Djamena, in hopes of a more stable life. But the country, in those years, was anything but stable. Leaders were deposed in coups, and fractious conflicts regularly erupted between the country’s many factions–along political, ethnic, and religious lines.

The south of the country, where Taigué was born and where his mother hailed from, was predominantly Christian, his father, from the arid Sahel region in the north–Muslim. Families of mixed religion, like Taigue’s, were not uncommon, despite the fact that those in government often fanned the flames of interreligious conflict—sowing division in order to retain their hold on power in a strategy inherited from French colonial rule.

In N’Djamena, Taigué began his education, but the violence of those years was a constant presence. “We went to the water to wash ourselves, to play,” he says, “There, we also found bodies. That is to say, it was everywhere, it followed me everywhere.” At the same time, a new force for change was about to enter his life.

“We went to the water to wash ourselves, to play. There, we also found bodies. That is to say, it was everywhere, it followed me everywhere.”

At 13, a choreographer from the National Ballet of Chad came to Taigue’s school to scout for aspiring dancers, gauging interest among the students. He remembers: “It was at that moment that I said, I want to dance.” He was asked to join the company, where students were trained in roughly 50 styles of traditional dance belonging to Chad’s rich tapestry of over 160 ethnic groups.

Taigué’s parents, wanting him to continue his education, encouraged him to attend high school with a focus on science. But when the family didn’t have the means to send him onward to higher education, and an opportunity presented itself, he returned to the artistic medium that first nourished him.

Taigué applied to join Les Jeunes Tréteaux, the first Chadian contemporary dance company. Founded in 1996–with funding from UNESCO–the company regularly sent its dancers to perform in Germany. With his acceptance into Les Jeunes Tréteaux, the world opened its doors: Taigué performed abroad, first in Madagascar, and later, in Europe. He began a workshop led by French-Beninese dancer and choreographer Julie Dossavi, who became a catalyst in his creative life. Reflecting on his time with her company, he says, “It was then that I realized: contemporary dance could be a tool of expression that allows us to transmit our story.”

Taigue teaching a dance workshop to young women refugees

“It was then that I realized: contemporary dance could be a tool of expression that allows us to transmit our story.”

After his pivotal encounter with Dossavi in 2003, Taigué’s career continued to reach new heights. He continued his training at prestigious institutions like the École des Sables in Dakar, Senegal and the Centre National de la Danse in Paris, and later worked in Germany, France, and the Netherlands, as well as the U.S. and Canada. All the while, Taigué did not lose sight of how dance had arrived miraculously into his life, and how it had become a personal salvation. He was determined to share the tools he had acquired with others who needed them.

In 2007, Taigué founded Ndam Se Na (“dance together” in the Ngambaye language), an organization devoted to fostering artistic and pedagogical dance projects in Chad. One of Ndam Se Na’s most impactful programs was its sustained work in refugee camps in southern Chad, where Taigué used dance as a means to restore dignity, foster resilience, and provide psychosocial support to displaced populations. This effort grew into the internationally recognized project Refugees on the Move (ROM), launched in 2012 with the support of African Artists for Development (AAD), extending its reach to Congo, Burundi, and Burkina Faso.

In his own country, Taigué watched how division between groups–the very division that fueled the violence he witnessed in childhood–maintained its foothold. After the inaugural chapter of SOUAR, a dance festival that Taigué co-founded in 2015, President Mahamat Idris Déby Itno asked to meet with him. With two Canadian artists at his side, Taigué prepared to pitch a new idea. The theme of the project was how art–and dance specifically–could be a tool for national reconciliation.

“There had been great mistrust between the youth in the north, the south, and the west for a long time,” Taigué explains. “How could we create a project within each of these regions, a table for dialogue?” Despite the interest that the president initially showed–and an offer to support the project financially–the money never arrived. The funds were siphoned off by political actors close to the seat of power. As Taigué fought to receive the funding that was promised to him, he became a thorn in their side. The international media attention that the SOUAR festival received, at one time a point of pride for the president, became cause for suspicion.

As anti-government manifestations rocked the country–and at times hundreds of protesters were killed–a climate of increasing paranoia gripped the regime. Taigué was routinely surveilled and accused of having links to the opposition. The funding that he had been promised for his national reconciliation project was suddenly held over his head as blackmail: “You know where the opposition is hiding,” they said, implying that if he gave them an answer they would give him the money. The pressure continued until one midnight in February 2023, when Taigué was summoned to appear before authorities the next morning. Knowing how easily he could be imprisoned and disappeared, he packed his things and left for Yaoundé, the capital of neighboring Cameroon.

After two weeks in Yaoundé, and with the support of a global artistic community behind him, Taigué gathered the funds to resettle in Paris, where he began a residency with Cité internationale des arts. While he experiences relative safety in France, and his children are nearby in Germany, Taigué is clear that transnational repression and his host country’s political climate remain perpetual sources of anxiety: “France is a country with free expression, at least for the French. But for the many who are living in exile–like myself–we do not truly have the freedom to express ourselves. We fear that we could still be followed, or that France could simply take us and send us back.”

“We fear that we could still be followed, or that France could simply take us and send us back.”

A workshop Taigué conducted with refugees in Germany who were involved in "Arab Spring" protests

No matter where he is in the world, Taigué continues to dream boldly of dance’s potential as a salve for the body–traumatized, dispossessed, or forgotten–and as a powerful means for storytelling. He is currently taking up a residency at Université de Moncton, in New Brunswick, Canada, where he was invited to teach his dance methodology. His upcoming project, titled Zone Rouge (“Red Zone”) will take place during his residency in Canada in collaboration with three Canadian and two Chadian artists, and is set to be ready in 2026. Drourkalang (“In the Midst of People”)–a piece which bears the traditional name Taigué was given by his father–will be realized by 2027, so long as funding permits.

Written by Elias Ephron, September 2025. Elias Ephron is the Media and Communications Officer at ARC – Artists at Risk Connection. He holds a BA in Political Studies and Spanish Studies from Bard College, and is now pursuing his master’s in Cultural Studies at KU Leuven. He currently resides in Brussels.