Javier Serrano Guerra – Boa Mistura

Graffiti Artist

Spain

By Juliette Verlaque, June 2023. Originally published in Art Is Power: 20 Artists on How They Fight for Justice and Inspire Change.

In the mid-1990s, a group of Spanish teenagers started painting graffiti together in the Barajas neighborhood on the outskirts of Madrid. One day, they came across a fanzine for pixação, a style of graffiti native to São Paulo, Brazil, that is known for its straight lines, sharp edges, and connection to youth culture and protests against inequality

“We fell in love with it,” remembers Javier Serrano Guerra, a member of the group. “We fell in love with how calligraphy can define a city.”

In 2001, five years after they started painting together, they chose a Portuguese name for themselves in tribute to pixaçao: Boa Mistura, or “Good Mixture,” which re – fers to the different backgrounds and perspectives that each member brings to the group. They have been working as a collective ever since, traveling to cities around the world and making public art in close partnership with local communities.

Serrano has been drawing for as long as he can remember and picked up a spray can for the first time at age 15. He quickly became enamored with the experience of painting outside, in the midst of his community and city, especially once he met the future members of Boa Mistura, who, like him, loved graffiti and hip-hop. “Kids from our same neighborhood would meet up to play football or basketball,” Serrano says. “We would meet up at night to paint graffiti or a mural or to sneak into a factory. It was not a friendship of sharing and telling things. It was a friendship of living through experiences and solving situations together.”

“Kids from our same neighborhood would meet up to play football or basketball. We would meet up at night to paint graffiti or a mural or to sneak into a factory. It was not a friendship of sharing and telling things. It was a friendship of living through experiences and solving situations together.”

For Serrano, the collective’s collaborative spirit has been instrumental in their creative process. “What this friendship did was dilute each individual ego into a collective ego,” he says. “Because when you realize that you have reached a certain level of admiration, respect, and trust for your colleagues, you let yourself go and arrive in a place where you could never have arrived alone. When we discuss a project, the idea of one person is shaped by the intervention of another, who lights the light bulb of the next person.… You realize that your idea has grown and improved so much and reached a totally new place you could never reach on your own. That makes you willing to give up your ego.”

In 2010, the collective received an invitation from the owner of a small art gallery in Cape Town to go there for an artistic residency. Living in Cape Town was a transformative experience. “Suddenly we find ourselves in South Africa, living in a very dangerous community … with prostitution, with drugs, with a gang operating one street away from where we slept,” Serrano says. “Having only worked in the European context, suddenly arriving in that place had an impact on us. We realized that what we had been doing before had no meaning in such a place.”

For the first few weeks, they felt “paralyzed,” unable to paint, Serrano says. It was only when they started walking around the neighborhood and speaking with members of the community that they came up with an idea for a project. The Boa Mistura members began painting a mural and encouraged the community, particularly children, to join them. “All of a sudden, we were neighbors,” Serrano recalls. Toward the end of their stay, a man who was starting a local cycling group solicited their help in painting blank containers for the bikes. They worked side by side with members of the community to finish the project in time for their departure. Through this process, they saw how the cycling club transformed from a place owned by a single individual to a place for the community.

The experience of learning from the community about their needs and their lives, and of subsequently working with the community to complete a project together—has shaped their approach to each of their subsequent projects in cities around the world, from Nairobi to Sao Paolo. “We tend to venture into the territories in which we work and we tend to live there,” Serrano says. “That makes us neighbors. And it is through the neighbors that we understand the context—the place, the community, and the people are the basis of everything. We prefer to understand places through the people who live there and know it best.”

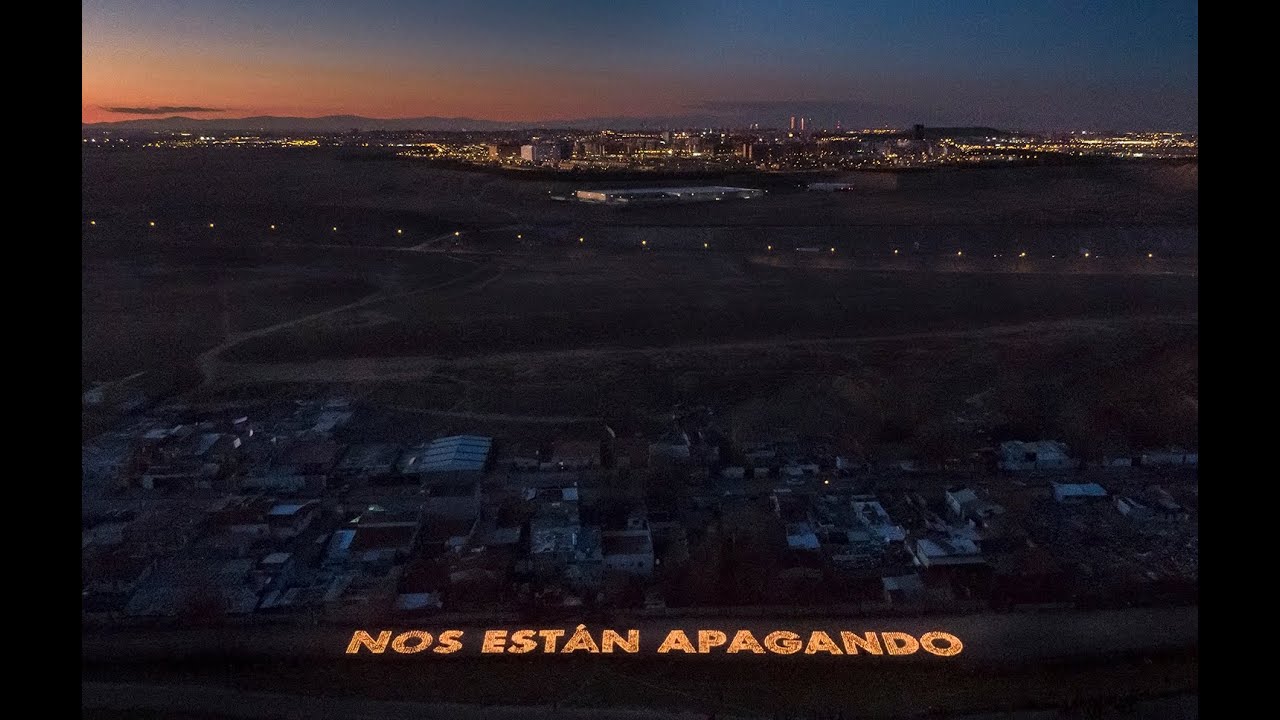

Nos están apagando. Boa Mistura. 2021. Art installation. Madrid.

Boa Mistura brought this approach back with them to Spain, where they often take on projects in Cañada Real, an informal settlement in Madrid that is considered the largest such settlement in Europe. Since November 2020, it has not had electricity, which the UN deemed a “children’s rights violation.” For one of their best-known projects, the collective asked each of the 4,000 people without electricity to share a candle with them, and they put the candles together in a public display, forming the words “Nos están apagando” (“They are turning us off ”). The project, which ran from December 2020 to January 2021, received significant news coverage and raised widespread awareness of the deplorable conditions in Cañada Real. “Something we’ve learned is that we can become loudspeakers for invisible places, which, because they are invisible, become worthless to the people who live there,” says Serrano. “The mere fact of turning them visible again gives them back their dignity that as human beings we must all have.”

“Something we’ve learned is that we can become loudspeakers for invisible places, which, because they are invisible, become worthless to the people who live there. The mere fact of turning them visible again gives them back their dignity that as human beings we must all have.”

Serrano knows that street art is, by its very nature, fleeting—and he’s fine with that. “We are not concerned with the durability of our work,” he says. “We don’t really care. It’s on the streets, under the rain, the wind, the sun, snow. A mural does not last more than 10 years in good condition. We understand the pieces are ephemeral, just as we as people are.”

As a result, Boa Mistura does not typically focus on the long-term impact of their projects. Instead, they assess impact during the project itself, based on the relationships they build with local communities and the sense of power and ownership that arises from the shared creative process. “It’s like planting seeds somewhere,” Serrano says. “They don’t always bloom. In fact, they rarely do. But there are times when they do bloom and that gives meaning to our existence.”

Soy Raíz. Boa Mistura. 2022. Art installation. Quito, Ecuador

The collective has recently returned to the locations of past projects to reconnect with their partners and see how the communities have evolved over the years. They have made such trips to Nairobi, São Paulo, Cape Town, and Antofagasta, Chile. Serrano says that returning to these locales was a powerful and affirming experience for him: “It reinforced what we had been doing, and showed me that our project had a meaning beyond the sharing, or even beyond the expression itself, but it also meant something to the people involved.”

In addition to their community-based projects, Boa Mistura does projects for art galleries, art museums, and collectors, which help them fund their street art. “Money is not an end goal to us, but is the means allowing us to act,” he says. “Financial means allow us to grab a van full of paint and drive 800 kilometers down the road, or to catch a plane and fly somewhere we have never been, to learn from how things are done in other places and develop a project on that place.”

Serrano believes that art draws its power from its existence as a physical manifestation of expression, as something you can touch and experience. “Art is something that may seem superfluous, but nevertheless it surrounds us and makes us understand things from other places,” he says. “Art has a unique ability to inspire people. It is a very powerful tool.”

Although the collective’s projects often touch on social and political themes, Serrano says that it is important to him to keep his creative process separate from broader social and political movements. “Independence is fundamental to me,” he says. “I want to be a free human being. I would not like to be at the center of a social movement—I would feel responsible for too many things. I would have to make agreements and pacts. As an artist, I want to be free to go into communities and say what I want, without having to abide by the rules of some social movement or political rulers.”

At the same time, Serrano believes that making graffiti is an inherently political act, because to draw on the streets is to break the law. Graffiti was highly criminalized in Spain until 2015, when it was reduced to a “minor infraction,” and the collective has at times been punished for their art. In 2012, for example, the authorities fined them $6,000 for painting gray rectangles on a wall that had once been covered with graffiti but was subsequently covered in gray by the city as part of Madrid’s zero-tolerance policy for graffiti. “Graffiti is your individual response to the environment in which you live,” Serrano says. “Graffiti is a political tool using a physical medium that is public space. Society does not allow it, laws do not allow it—but we did it and we continue to do it, and all the graffiti artists do it. We accept that there are rules, and we break them.”

At times, the collective has sought to work with the government instead of circumventing it—but the government has not always been receptive to their advances. In 2014, for example, Boa Mistura asked Madrid’s city council for permission to work on a project that involved painting crosswalks, knowing that the group would face a heavy fine if they were caught doing so illegally. After the government declined to grant permission, Serrano says, the group went out at night, “dressed as ninjas,” to carry out the project. The government couldn’t prove that Boa Mistura was behind it, so they were never sanctioned.

Thankfully, the tides of change were on their side. In 2017, the city elected a new, more progressive mayor, Manuela Carmena, who launched a project to make Madrid the poetry capital of the world. She turned to Boa Mistura for help, and in 2018 the collective painted 1,000 crosswalks around the city. The project, Versos al paso, secured the participation of more than 25,000 citizens, who shared stanzas from poems with the city for use in the crosswalks.

“It was interesting how an illegal project, rejected before, years later became public policy, with significant impact on the urban landscape of the city,” Serrano says. “We are made of clay, we work in the clay. We are not some intellectual artists, who are dedicated to generating such an elaborate message. We go to the territories to build something with our hands and the neighbors’.”