Oleg Sentsov

Filmmaker, Writer

Ukraine

Oleg Sentsov –filmmaker, writer and activist– is a promising director and screenwriter whose daring activism has inspired many in Ukraine and abroad to challenge Russia’s influence on Ukrainian state affairs, and its occupation of Ukrainian territory.

This course of art and activism originally arose out of hobby. After studying economics at Kyiv National Economic University (1993-1998), Oleg owned and operated a computer club in Simferopol for many years. During this time, he took courses in film directing and screenwriting in Moscow and directed two short films: A Perfect Day for Bananafish (2008) and The Horn of a Bull (2009).

In 2012, Oleg released his first feature film Gamer, which focuses on a young Ukrainian gamer and the struggles he faces in Simferopol, living with his single mother. The film won a spot at the Rotterdam International Film Festival where it debuted to much praise. This success helped Oleg secure enough funds for his second film Rhino, which entered production during the outbreak of the Euromaidan protests against then-President of Ukraine Viktor F. Yanukovych.

The protests, which spread across Ukraine in the fall and winter of 2013, politicized Oleg. He became an active member of the “Automaidan” contingent of the Euromaidan movement, in which Ukrainian car owners would support protesters with supplies, participate in rallies, and serve as agitators against the pro-Russian government.

Following the fall of the pro-Kremlin government in February 2014 and Russia’s occupation of Ukraine, Oleg continued his work opposing Russian encroachment on Ukranian sovereignty. Drawing on his experience with Automaidan, Oleg delivered supplies to Ukrainian soldiers surrounded by Russian troops.

That May members of Russia’s Federal Security Service crossed the border into Crimea and then located and detained Oleg. He was then brought to Moscow where he and a co-defendant, Aleksandr Kolchenko, were convicted on suspicion of terrorism. During a trial hearing on August 25, 2015, Oleg asserted that Russian officials has tortured him in an effort to force a confession, and his body showed signs of beatings.

Oleg was accused of founding a Crimean branch of a banned Ukrainian nationalist group called Right Sector, carrying out two terrorist acts, and plotting the explosion of a statue of Lenin in Simferopol. These claims were denied by Oleg and dismissed as fabrications. Likewise, the key witness, Gena Afanasev, later claimed that her testimony had been forced through torture.

Ultimately, the Russian courts sentenced Oleg to 20 years in prison and transferred to a Siberian prison in Yakutsk.

This sentence sparked international criticism and an outpouring of support for Oleg, who quickly became a symbol of Russian state oppression. Isolated from Ukrainian officials and international authorities, Oleg’s Ukrainian citizen was effectively stripped. In 2016, the Russian state refused Oleg’s extradition claiming he was a Russian citizen.

Despite these barriers, Oleg was able to smuggle a letter out of prison a year after his arrest:

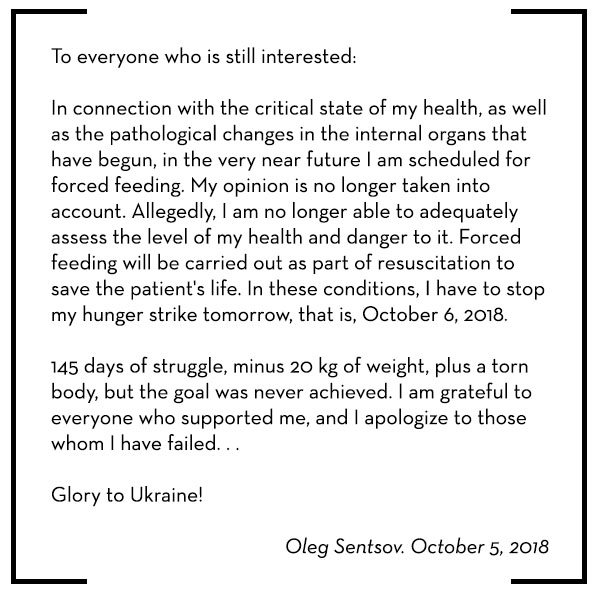

Excerpts in English of Oleg Sentsov's letter, October 5, 2018.

“There is no need to pull us out of here at all costs. This wouldn’t bring victory any closer. Yet using us as a weapon against the enemy will. You must know: we are not your weak point. If we’re supposed to become the nails in the coffin of a tyrant, I’d like to become one of those nails. Just know that this particular one will not bend.”

— Oleg Sentsov

When caught, Oleg was placed in solitary confinement for 15 days as punishment. Russia has a long and dark history of internment and dislocation. Oleg’s treatment is textbook state suppression and was meant to send a message to artists and activist both in Russia and abroad challenging the authority of the Russian state. Putin has rejected calls for Oleg’s release, but Oleg’s spirit remains unbroken, and international pressure continues to mount.

UPDATE (2/07/22): Sentsov’s latest film, Rhino, premiered in the Venice Film Festival’s Horizons program on September 10, 2021. The film is a “violent portrait of a young man who rises to become the leader of a gang in 1990s Ukraine.”

UPDATE (9/7/19): On September 7, Ukrainian filmmaker and 2017 PEN/Barbey Freedom to Write Award honoree Oleg Sentsov was freed from a Russian prison after more than five years of unjust detention. Read PEN America’s statement here.

UPDATE (10/25/18): On October 25, Oleg Sentsov won the Sakharov Human Rights Award, the first Ukrainian to ever win the award.

UPDATE (10/5/18): On October 5, Sentsov announced that he will end his hunger strike on October 6, after 145 days. The letter from Oleg Sentsov can be found here, and excerpts in English below.

UPDATE (6/14/18): Sentsov has been on hunger strike for an entire month. In this dire situation, the campaign to #SaveOlegSentsov has reached a boiling point. Read PEN America’s letter to the Kremlin and join Margaret Atwood, J. M. Coetzee, Chimamanda Adichie, and numerous human rights organizations in demanding his freedom and the freedom of all Ukrainian political prisoners in Russia.

By Ben Ballard, April 2017.