Aslı Erdoğan

Writer

Turkey

“I am not a ‘novelist’ in the traditional sense of the word, nor even a storyteller,” Turkish novelist and human rights advocate Aslı Erdoğan said in a translated interview with Erkut Tokman for World Literature Today. “The most important element of my literature is language itself. The words reflect, invoke, and echo each other; obscure shadows gather in their corners, silence is filled with meaning as much as words are, while darkness and void are as signifying as light.”

Writer, journalist, and physicist—Aslı Erdoğan has done it all. After studying Computer Engineering at Boğaziçi University, Erdoğan went on to do research as a particle physicist at the European Council for Nuclear Research (CERN) and earned a subsequent degree in Physics from Boğaziçi. She began her Physics PhD program in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, before deciding to leave her scientific career to pursue writing.

Given her passion for words and literature, Erdoğan knew that she wasn’t destined to stay in academia full-time. She went on to become a bestselling writer and columnist, whose works are published in Turkish and have been translated into twenty other languages. She is the author of eight books and has received more than 35 awards, including the Erich Maria Remarque Peace Prize, the Simone de Beauvoir Award, the Vaclav Havel Library Foundation Award, the Chevalier des Arts et Lettres, the Karl Tucholsky Award, the European Cultural Foundation Award and the SAIT FAIK Award. Her work has been adapted off the page — into theater, classical ballet, radio, a short film, and even opera.

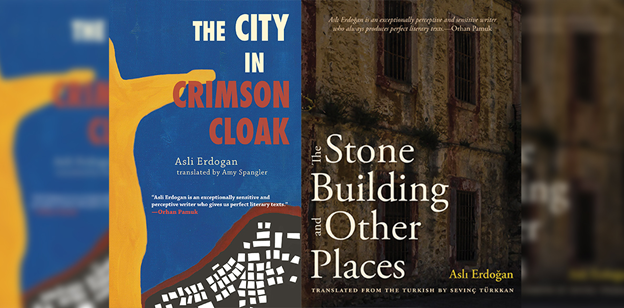

Erdoğan is best described as a painter with words, and she has created some of the most strikingly vivid colors in recent literature. One of her earlier novels, The City in Crimson Cloak, published in 1997, explores the identities and baggage that we all carry through life, the feeling of longing for and separation from the places we belong, and the modern political climate in Turkey. Many of Erdoğan’s narratives revolve around the intersections of being a human with a story to tell and living in an increasingly political world, where simply adhering to the status quo isn’t a possibility for most.

Photograph by Petra Paul II

Photograph by Anna Sigvardsson for the Göteborg Book Fair

The covers for two of Erdogan’s novels

As revealed by PEN America’s second annual Freedom to Write Index, Turkey is one of the world’s most frequent jailers of writers and public intellectuals. Freedom of expression continues to come under attack by President Erdoğan’s increasingly restrictive administration, and international pressure critiquing Turkey’s repeated human rights violations continues to mount.

During her imprisonment, Erdoğan, who has several health ailments, was held in terrible conditions and regularly denied medical requests. She has since been diagnosed with systemic sclerosis, or CREST syndrome, a rare and devastating auto-immune disease that was exacerbated by her time in prison. While Erdogan was detained, and during the subsequent legal attacks, including an arbitrary travel ban that restricted Erdoğan’s mobility and ability to write freely, international organizations like PEN International and PEN America advocated for her freedom. After her travel ban was lifted in June 2017, Erdoğan escaped to Germany in self-imposed exile, while the trial continued intermittently for several years in her absence. In February 2020, Erdoğan was acquitted of all charges. However, the legal persecution only ebbed for a few months: In June 2020, a new prosecutor appealed her case to a higher court in Istanbul, and the acquittal was cancelled. She faces charges of sedition, membership of a terrorist organization, and use of propaganda. She now faces up to nine years in prison.

Despite these ongoing challenges and health difficulties, Erdoğan courageously continues to write from Germany and remains an icon of free expression and the fight for human rights in Turkey to readers and activists around the world. She recently spoke about her experiences in ARC’s Safety Guide for Artists, a resource to help artists understand and navigate risk.

To learn more about Erdogan, visit her website at https://aslierdogan.net/.

By Finley Muratova, May 2021. Finley Muratova is a New York University student, hailing from Moscow, Russia, and pursuing degrees in journalism and environmental studies. Finley’s work centers survivors of sexual violence and they’re passionate about improving the Title IX processes for victims of gender-based violence.