Bart Was Not Here

Visual Artist

Myanmar, {Burma}

By Juliette Verlaque, June 2023. Originally published in Art Is Power: 20 Artists on How They Fight for Justice and Inspire Change.

In March 2021, Burmese artist Bart Was Not Here parked his car outside his art studio in Yangon and entered the studio. Several hours later, he heard gunshots—and realized that someone had shot a bullet into the empty vehicle. In that instant, he knew that he needed to leave Myanmar.

Six weeks earlier, Bart, a visual artist, had risen to prominence for publishing a viral digital art series, Seeing Red, which depicted his live reactions to Myanmar’s Spring Revolution, a series of mass demonstrations that broke out following the country’s brutal February 2021 military coup. By day, he joined the protesters on the streets, handing out posters and flyers to demonstrators. By night, he worked on Seeing Red, frequently reaching an audience of 400,000 people.

To Bart, both his digital illustration series and his involvement in the protests were ways of exercising his civic duty. In his conversations with ARC, he points to the countless others in Myanmar who supported the movement however they could, down to the bus drivers and other motorists who pretended that their engines had broken and physically blocked military vehicles from attacking protesters. “Everybody was pulling their weight, and I was part of it,” Bart says. “I was pulling my weight as an artist. I was using my tool and ability. That’s how I saw it.” After years of all-consuming repression in Myanmar—where his fellow citizens had to keep their thoughts and desires to themselves—he saw that the protest movement was filled with disparate goals and narratives, and felt that his role as an artist was to pull these narratives together. “My job,” he says, “was to keep my eye on the ball and be profound in protesting.”

Omen. Bart Was Not Here. 2021. Digital Illustration.

The Spring Revolution was not the first moment of national unrest that shook Bart’s political consciousness and changed his trajectory as an artist. When he was in sixth grade, he and his peers were sitting in class when they noticed a commotion on the street outside. They heard gunshots and watched as a group of monks marching down the street was encircled and attacked by a group of soldiers. “The monks were sandwiched, and it was just like a cartoon,” he recalls. “It was like a ball of dust, and you could see nothing. And then the dust cleared, with slippers, robes, and blood on the street. That was the moment when I realized: I don’t think that’s supposed to happen. I don’t think that’s supposed to happen in a country.” That attack was part of Myanmar’s Saffron Revolution of 2007—a series of protests against Myanmar’s ruling military junta, led by students, political activists, women’s groups, and thousands of Buddhist monks, that was violently put down.

“It was like a ball of dust, and you could see nothing. And then the dust cleared, with slippers, robes, and blood on the street. That was the moment when I realized: I don’t think that’s supposed to happen. I don’t think that’s supposed to happen in a country.”

Yangon. Bart Was Not Here. 2016. Mural installation.

Although most of his peers in graffiti had never learned their craft through formal instruction, Bart decided in 2012 that he wanted to go to art school. “I knew that I wanted to make things for the rest of my life,” he says. “I didn’t want to do anything else, and I figured that I had to go to art school to learn the ins and outs of the whole thing.” He studied fine art at Lasalle College of the Arts in Singapore and spent the next few years traveling, learning, and creating. In 2018, he returned to Myanmar, opened an art studio, and launched a successful career as an artist, painting, making prints, and doing commissions for advertisers.

Three years later, on February 1, 2021, the Tatmadaw—Myanmar’s military forces—took control of the country in a coup d’état, declaring a state of national emergency. They immediately placed the leaders of the main governing party, the National League for Democracy, under arrest. Hundreds of thousands of people took to the streets and ignited the Spring Revolution.

On February 2, the second day of the coup, Bart began publishing Seeing Red. “My message was to preserve the sentiment that we are against everything the military stands for,” he says. “If the military is pro-Burmese supremacy, we’re against that. If they stand for preserving tradition and Burmese culture, we’re against that.” He posted the series every day on Facebook and Instagram, starting with the word “Disobey” emblazoned in white letters against a red background. The series quickly went viral and struck a chord with the protesters. He heard of at least two people who had tattooed his artwork on their bodies—one of whom was arrested immediately afterward.

Bart also hit the streets to join the protests, handing out posters and signs with slogans and illustrations, such as the three-fingered symbol that became an emblem of the protests, inspired by the popular dystopian series The Hunger Games, where rebel protesters use this gesture as a symbol of solidarity and defiance. Though before the protests he had been partial to traditional media like canvas and walls, he now turned to digital media, which would enable him to “get rid of the evidence immediately.”

“Art is alchemy, taking a little bit of this, a little bit of that—a little bit of this experience, a little bit of ideas, a little bit of your influences—and you put it all together so eloquently that they all fall in line and it becomes a new idea and a new work.”

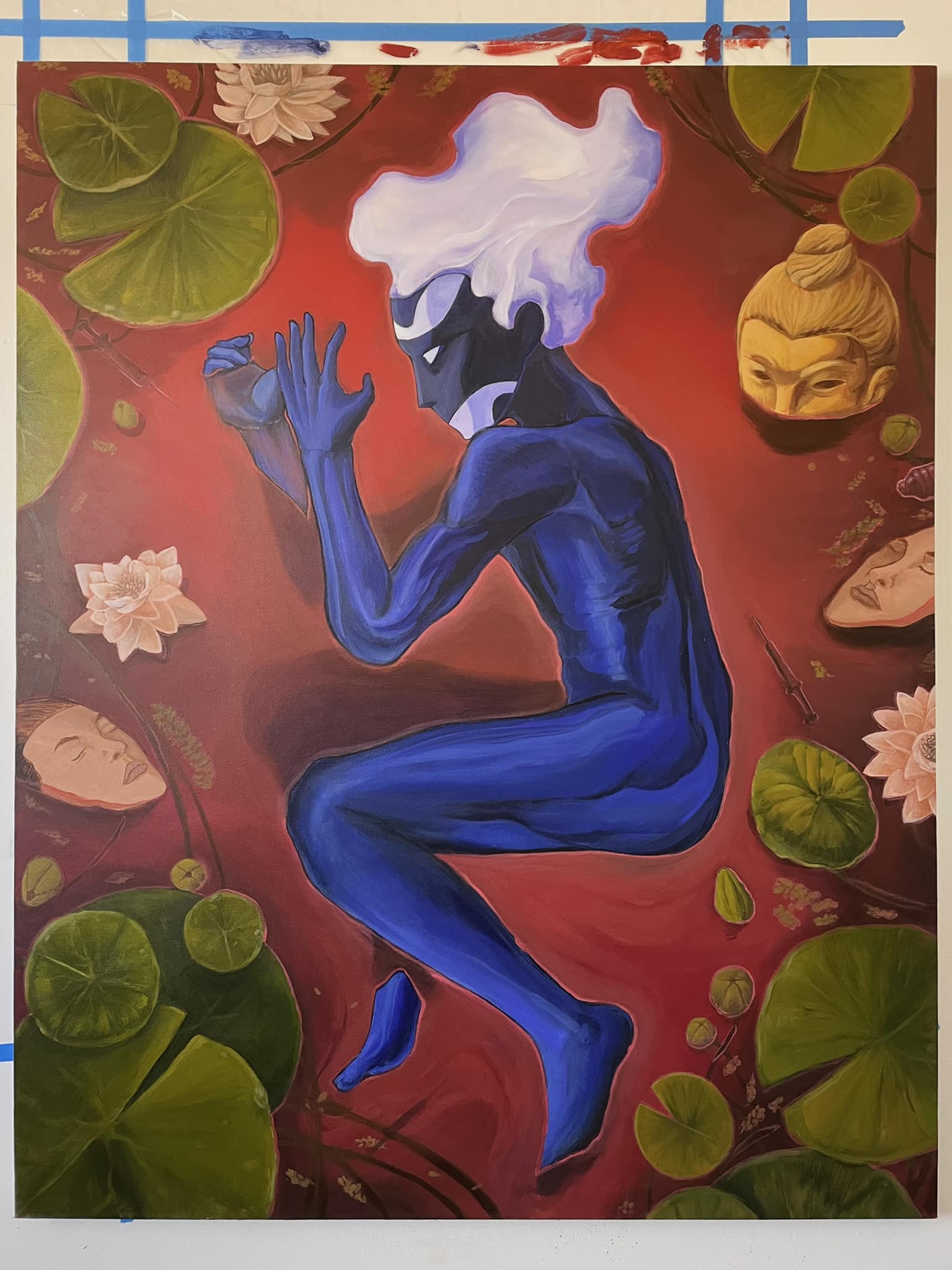

From the Womb to the Tomb. Bart Was Not Here. 2022. Acrylic on canvas.

Despite his involvement in the protests, Bart chafes at being typecast as a political artist and attributes this resistance to being put in a box to an anti-institutional streak that manifested in renouncing his religion and acting out in school when he was growing up. “I think people can label me as a political artist, because I did this series for one year,” he says. But as he moves onto different projects and explores new themes, he says, “I think I’m just showcasing that I’m well-rounded, and I’m not a monolith, I’m not one dimensional. I make artwork so that I can tell my own story, and I can be creative.”

At the same time, he believes that to create art in Myanmar is inherently a political act. “You are actually creating and exercising freedom, which is the polar opposite of what the military in Burma represents,” he says. “So as a creative person, even if you don’t do political work, you are political because you are refusing the military regime” and its propaganda.

Bart acknowledges that art can provoke social action, but for him that’s not what it’s about. “Art is above everything else,” he says. “Art is alchemy, taking a little bit of this, a little bit of that—a little bit of this experience, a little bit of ideas, a little bit of your influences—and you put it all together so eloquently that they all fall in line and it becomes a new idea and a new work.” He believes that art draws its power from its ability to present people with new and different realities and to inspire them to want those realities.

After the unknown assailant shot at his car, Bart says, “I started planning for a way out.” He stayed away from his studio for several months, and when he returned in May he discovered additional bullet holes inside the studio itself. “It was getting eerie,” he says. Because he worked under a nom de plume, he found that he was not a visible target and was able to leave the country easily, without being stopped at the airport.

After leaving Myanmar in June 2021, Bart traveled to Paris, where he lived for a year, and then to Los Angeles, where he spent several months, before settling down in New York City in November 2022. He accepts—and even takes pride in—the label of being in exile. “I wear it as a badge,” he says, “because you pissed some people off enough to not be able to go back to your country.”

For Bart’s next series—his first since going into exile—he plans to focus on the experience of being an immigrant and moving from city to city and country to country. “I think it’s really exciting to be a part of that immigrant lore, because we travel with stories … and tell other people the stories of our land,” he says. “I had to leave my home, but I’m finding home and I’m creating home as I move in the world. I believe that the most courageous thing one can do is to leave home and the comfort of home and go be a ‘no one’ somewhere and start from scratch. I think that’s very brave.”