Sasha Skochilenko

Visual Artist, Musician, Poet

Russia

ARC Interview with Sasha Skochilenko

— After being released and going into exile, what are the main challenges you face, and how do you cope with them?

My main challenge since being released from prison, is to convey to people that I am not an activist. I have never been involved in activism; I worked as a journalist, and my actions after the war are driven purely by personal motivation. I didn’t go to prison to fight the regime; I went to show others that it is possible to live according to principles of peace, love, and understanding. That even such a dreadful situation can be used to make things brighter.

So now it’s important for me to convey to people that I am an artist and a musician; I cannot spread myself thin across all activities in the world. Even the most important ones like activism. I insist that my act was an act of a citizen, not an activist. I am close to civil protest, and the action I participated in was a popular movement. I believe that everyone can take part in collective gestures based on personal reasons.

It seems to me that the issues of political prisoners, namely their mental health—in other words, social issues—are the most important and are what truly concern me. Therefore, I try to explain to everyone that there is no need to call me to political conferences or forums; I won’t share my opinion on politics. I don’t even read political news right now. I don’t read any news at all; it’s too stressful. My phone gives me migraines and panic attacks.

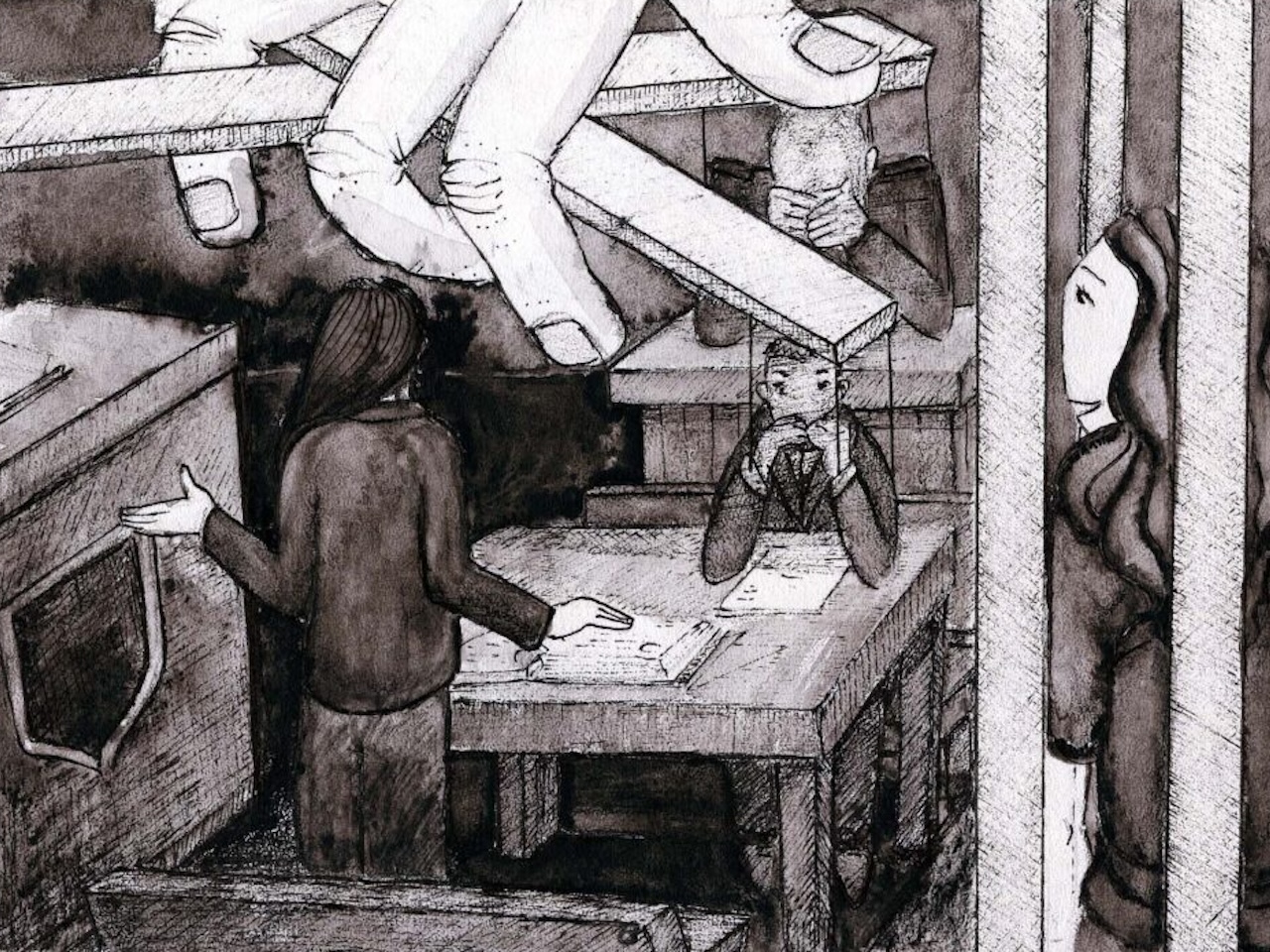

Depiction of Sasha's ordeal in court, drawn while she was imprisoned. Sasha drew myriad sketches of prison life and managed to send them out to supporters during the time of her detention.

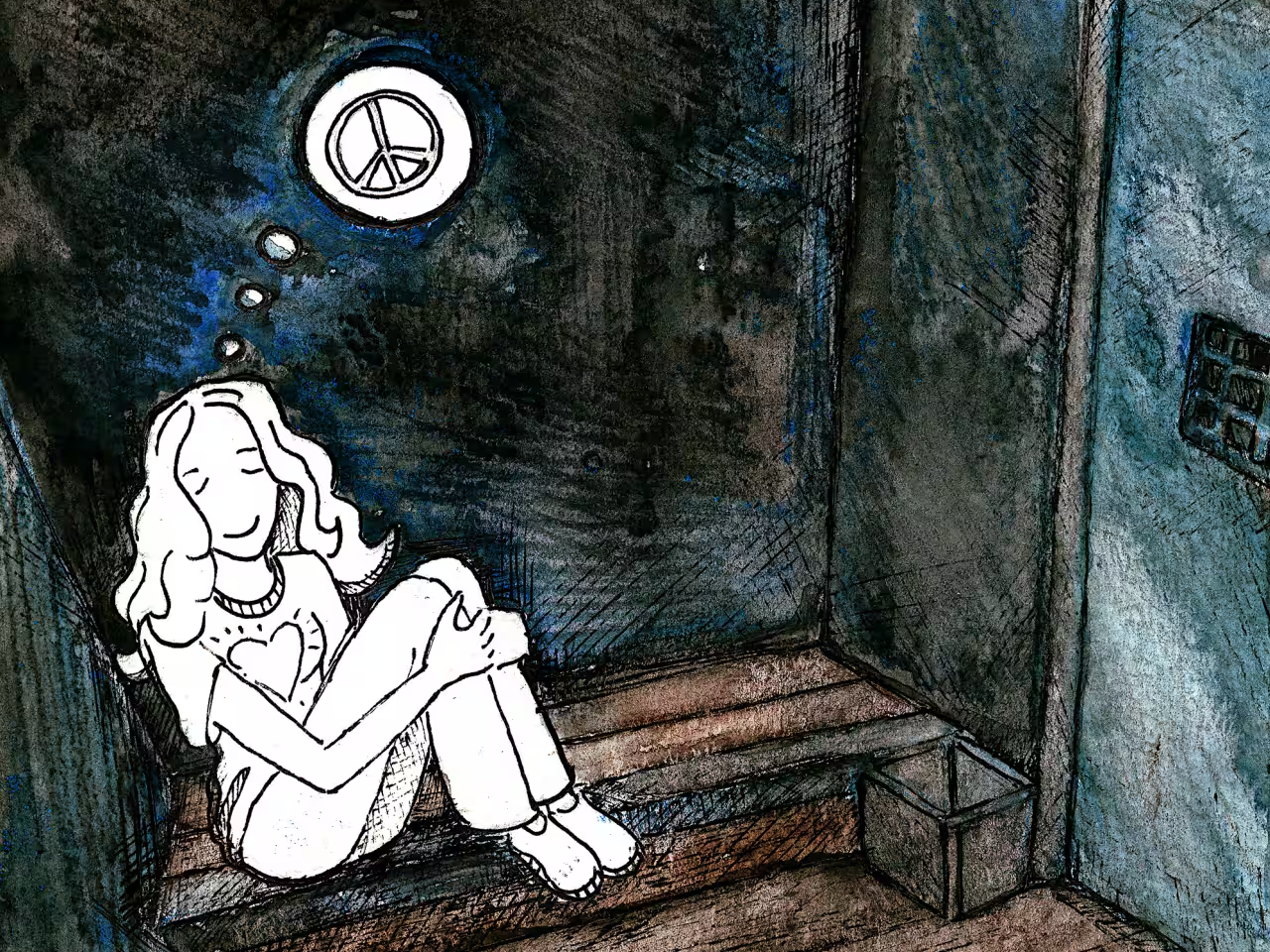

when Skochilenko was sentenced, she was permitted to give a final statement — a speech she called “Yes, Life” - “Even though I am the one in the cage, perhaps I am much freer than you … I have no enemies. I’m not afraid to remain poor, I’m not afraid to lose the roof over my head. I’m not afraid to seem strange, vulnerable, weak, funny. I’m not afraid to be different from others. Perhaps this is why my state is so afraid of me and others like me — since it keeps me in a cage, like a most dangerous animal.”

— How do you assess the current situation for artists and cultural figures in Russia, and what are the main dangers they face today?

It’s important to say that I’ve been in exile, outside of Russia, for seven months now. Before that, I spent two and a half years in a pre-trial detention center, which is like a separate archipelago. It’s not the Gulag Archipelago; it’s probably incomparable—a fundamentally new phenomenon. In Russia, things change every day. What you wouldn’t be jailed for yesterday could be the very reason you get imprisoned tomorrow, even if you did it years ago. So, I can’t assess the actual level of danger.

But what I do know for sure is that there are artists in Russia. I know this because I communicate with them. I’m not talking about official positions—the artists’ union, for example. I’m talking about people who create not on commission but from their soul and conscience.

They are amazing. They write and create on topics that are the most important and complex right now. I dream of showcasing all of them in Europe. They are incredibly original, and the restrictions they face only fuel their creativity with more ideas on how to bypass the bans.

Also, I know for sure that artists will never disappear in Russia. Russia’s creative force is immense. Creativity isn’t where everything is positive and comfortable. Creativity is needed when there is no hope left. It provides an irrational light, an irrational support.

Even those artists who are in prison in Russia continue to create. Despite all the difficulties, despite the harsh conditions and long working hours. A person in prison, who has no strength left, takes a pen and draws. These are the artists, not those who paint generals on horseback.

You must also understand that these people, these artists, are impoverished. In Saint Petersburg, we had a chat called “Friends Want to Eat.” It brought together the most creative people in the city, united by the need for food. None of us worked official jobs; we worked on construction sites, in warehouses, and as cleaners. We earned very little, but this work didn’t steal our creative energy. We could engage in creativity and not be tied to the state.

We had arrangements with shops and vegetable stalls that allowed us to take food that they couldn’t sell. . People came, picked it up, and posted in the chat—there are tomatoes or bananas. You could meet really great people and eat for free.

I would also mention a challenge: themes and words are disappearing from the artist’s toolkit. They have become “dangerous.” You can’t talk or write about drug issues, although Russia has huge problems with drug use. Long prison terms, the number of deaths from drugs—it’s all enormous. There’s no information, no honest conversation on this topic in Russia. Even when someone on TV says, “I’ve overcome addiction,” censorship cuts out the name of what they’ve overcome.

It’s impossible to talk about “peace”—peace, pacifism, such words and topics no longer exist.

You can’t talk about love, either. Not everyone is heterosexual. I often talked about my relationship with my partner Sonia, about love; in Russia, I could have been jailed for that. We’ve always shared this openly, and perhaps people understood that it was love, including the investigators. They could have opened another case against me, but apparently, they saw it was love and stopped.

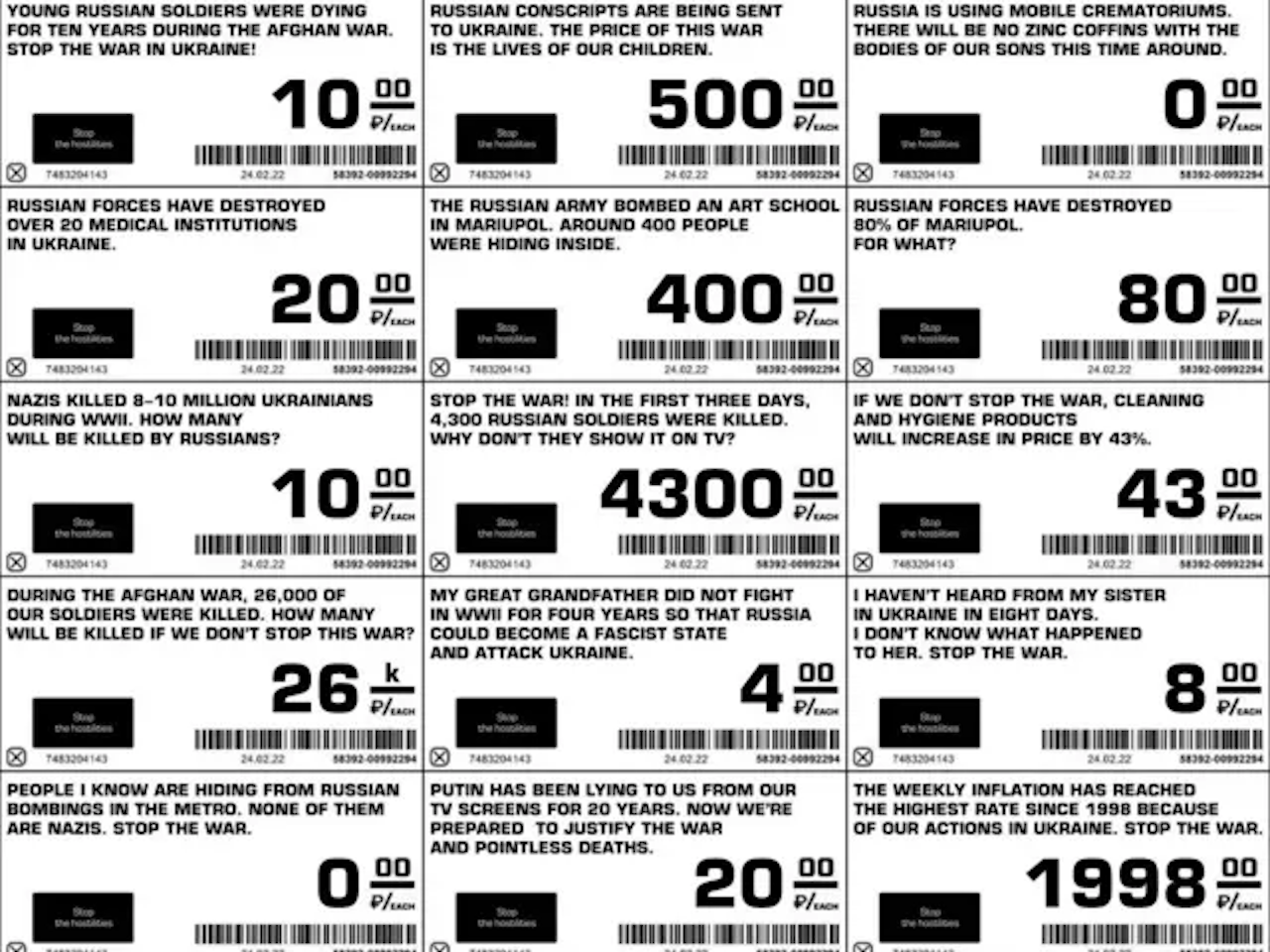

Weeks after Russia's full-scale invasion of Ukraine, Sasha Skochilenko protested by replacing supermarket labels in a St Petersburg supermarket with anti-war messages, a small act called for by a feminist collective. The replacement labels read: "The Russian army bombed an art school in Mariupol. Around 400 people were hiding inside," and: "My great grandfather did not fight in WWII for four years so that Russia could become a fascist state and attack Ukraine."

Sasha spoke with Zima Magazine about her experience and her work: "In my work, I wanted to show a cross-section of one society: many faces of people of different ages, religions, colors, genders… It is not completely clear whether these people are silent or screaming, or whether they are screaming inside but cannot say anything out loud. My mouth is not screaming or clamped shut, I am smiling. I am in prison, but thanks to this I am freer than many, because I am no longer afraid of being locked up. Prison has made me a more diligent person – I can now persevere and painstakingly draw every detail, something I lacked before. This is one of the few works I was able to do with my new tools in prison." (see: zimamagazine.com/en/2024/10/even-the-smallest-thing-can-make-a-difference-big-interview-with-sasha-skochilenko/)

— Can you share your personal experience of recovering after incarceration? What was the most challenging, and how has it affected your identity as an artist and creative person?

I can’t say that I’ve recovered from prison because there hasn’t been a period of recovery. When I was released, I needed to thank everyone; I needed to attend all the conferences I was invited to because I had a lot of media power, and I understood that this power had to be used to tell people about political prisoners. I got very tired. It was a big stress for me. I started experiencing severe migraines.

Of course, I have PTSD. And that’s not something that just goes away; it needs to be treated. Typically, PTSD symptoms manifest about six months later, so I will be getting treatment now. I developed claustrophobia. When I feel hungry, I start to panic. I think it’s because, in the jail, I often couldn’t eat on time. I have celiac disease, and I can’t eat most foods, so in prison, I often faced the choice of being completely without food or eating something that would cause a lot of pain later. People often face relationship problems after prison; Sonia and I went to therapy. We have now reached absolute harmony, and finally, our cats have joined us.

Physically, I was able to recover. My legs don’t hurt after walking anymore; in prison, there was so little physical activity that I simply didn’t walk.

Has prison affected my identity? No! I was an artist before prison, and I remain one. I’m just more well-known now. You see? The difference between a known and unknown artist is nothing. It doesn’t exist. You simply have a different level of support and a different level of communication. Fame isn’t talent or skill. I always thought I might die in obscurity, and I wasn’t very concerned about it. I just wanted the ability to create. It just so happened that what I know and do is in demand, not in peacetime, but in times of crisis. I’m a patient, strong person. I never questioned whether to plead guilty or not. I immediately knew I wouldn’t agree with them—I simply couldn’t. I didn’t want to go to prison or die on principle; I just wanted to live according to my values. Of course, I wanted to be free, but on my own terms.

In 2014 Sasha created a comic book, titled “A Book About Depression.” She posted it for her friends to understand why she struggled and sometimes couldn't go to work even though she looked healthy. She continues to be outspoken about mental health issues, including those she experienced while imprisoned.

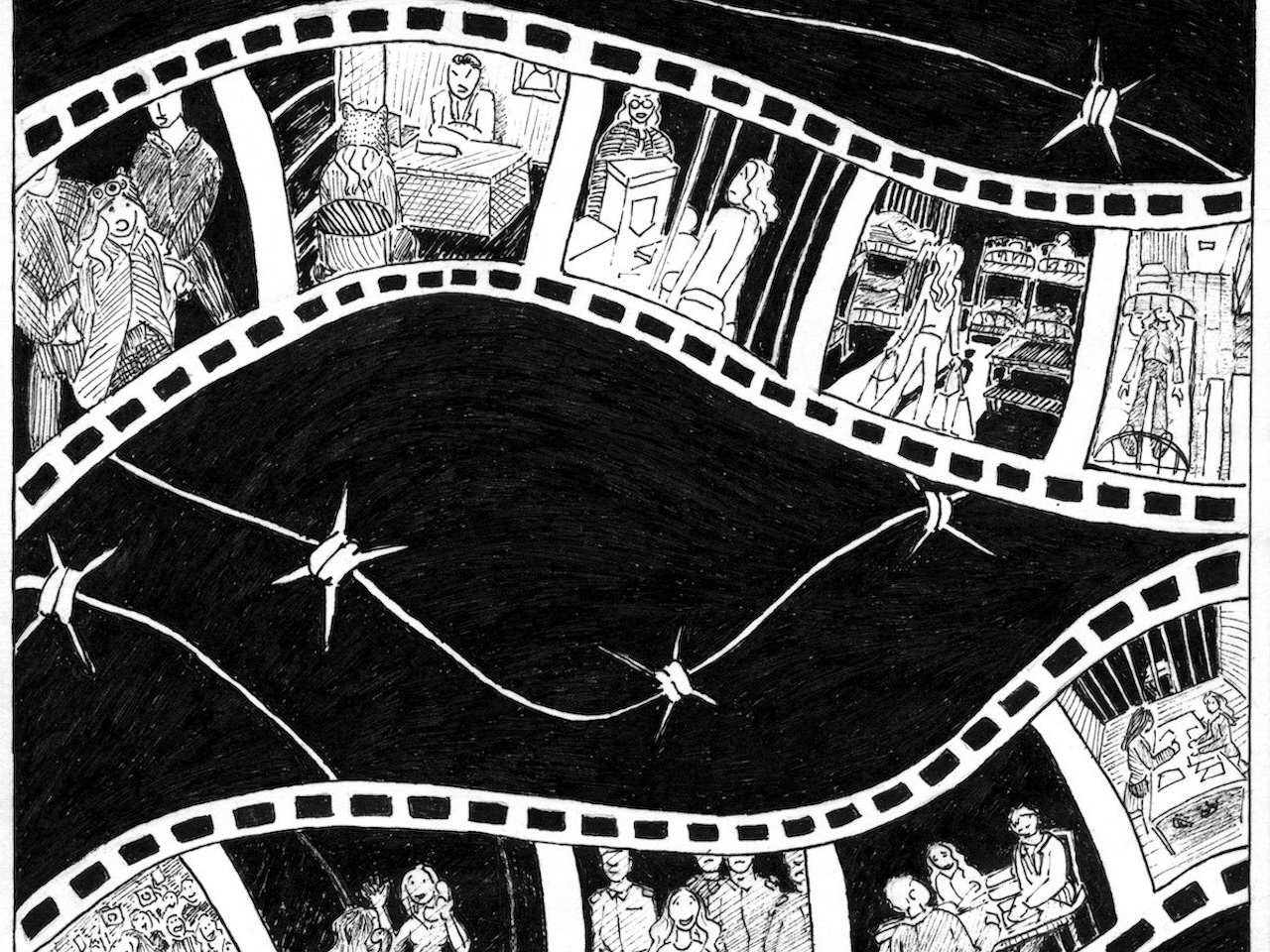

Sasha depicted the ordeal of her trial and imprisonment as a film strip, suggesting the "show" aspect of the case.

— Your relationship with your partner has always been in the open. That’s a huge rarity in Russia. Why didn’t you hide your relationship, and weren’t you afraid it might worsen your situation? What is the current state of the LGBTQ+ community in Russia?

The thing is, when I was ready for a serious relationship, my goal was to find a woman who would be prepared for one. It was very important for me that she wouldn’t be ashamed of our relationship, that we could kiss on the street. I’ve always been bold in this regard, and it was very unpleasant when my partners would say, “Don’t hold my hand now because someone I know is coming.” Or, “Let’s leave the apartment separately in the morning so no one knows.” That was absurd to me. When it’s about true love, I don’t care about the danger. As a result, the strength of our love protected us. Even in the detention center, everyone immediately understood. They saw that Sonia was someone who would fight for me to the end. Even the staff in the detention center understood that; they saw that it was love.

So I was looking for a brave girl, and I found Sonia. Sonia is fearless, despite all her outward tenderness and femininity. I often thought about how it might be dangerous for her, knowing that she had received threats from homophobes. But Sonia is a courageous person.

Now, what I know about the LGBTQ+ community in Russia is that these people exist, that they continue to live there, but life is very difficult for them, often in secret. I remember when it all started, when the law banning so-called LGBTQ+ “propaganda” was about to be enacted, I stood in pickets in St. Petersburg, and there were about 20 of us standing there. The rest of the community didn’t believe us—they said nothing bad would happen, that the law would only affect children. Well, now there are raids in gay clubs. It’s very frightening—people are being detained, beaten, and raped.

— During your imprisonment and subsequent exchange, your case attracted significant attention. Has this attention followed you, and have you managed to turn it into support for yourself or others?

Unfortunately, the attention has remained. I say unfortunately because I’ve realized that I don’t want fame. Even before my arrest in St. Petersburg, I was becoming known, and I already understood that fame leads to the disappearance of personal time and a personal life, and an increase in communications. David Bowie has a song called “Fame,” where he sings, “Fame! What you need you have to borrow.” That’s exactly how it is. There isn’t more money; that’s a fact. But I manage to secure help for others. I try to post a few entertaining things on Instagram so as not to bore people with requests for help, and then I make posts with requests for assistance.

Recently, Lyudmila Razumova, an artist currently in prison, declared a hunger strike to be taken to the prison hospital. She had been on hunger strike for 11 days, and it’s known that people most often die from dry hunger strikes. All that needs to be done is to flood the prosecutor’s office with appeals. It works. The penal service isn’t the FSB; they’re sensitive to reputational scandals. They fear being yelled at by Moscow because it’s a hierarchical structure.

When there are many such appeals, they’re eventually forced to comply with demands. I understood that social media is a simple algorithm—I needed as many people as possible to see my post, send appeals to the prosecutor, and help Lyudmila Razumova. If that means arguing with someone in the comments, I’m ready.