In the Middle of "Waiting"

Monorom Polok for Shafiqul Kajol Islam

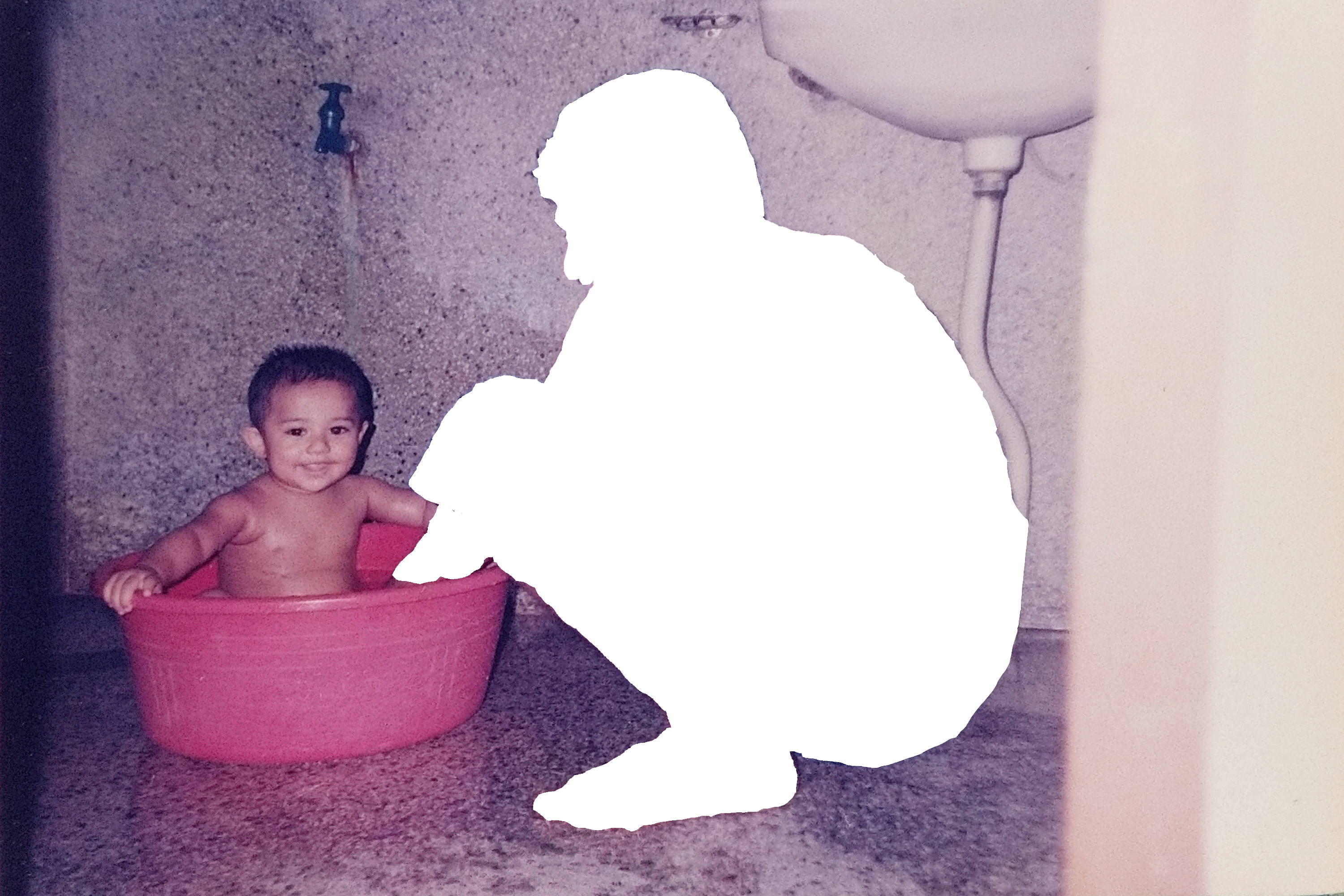

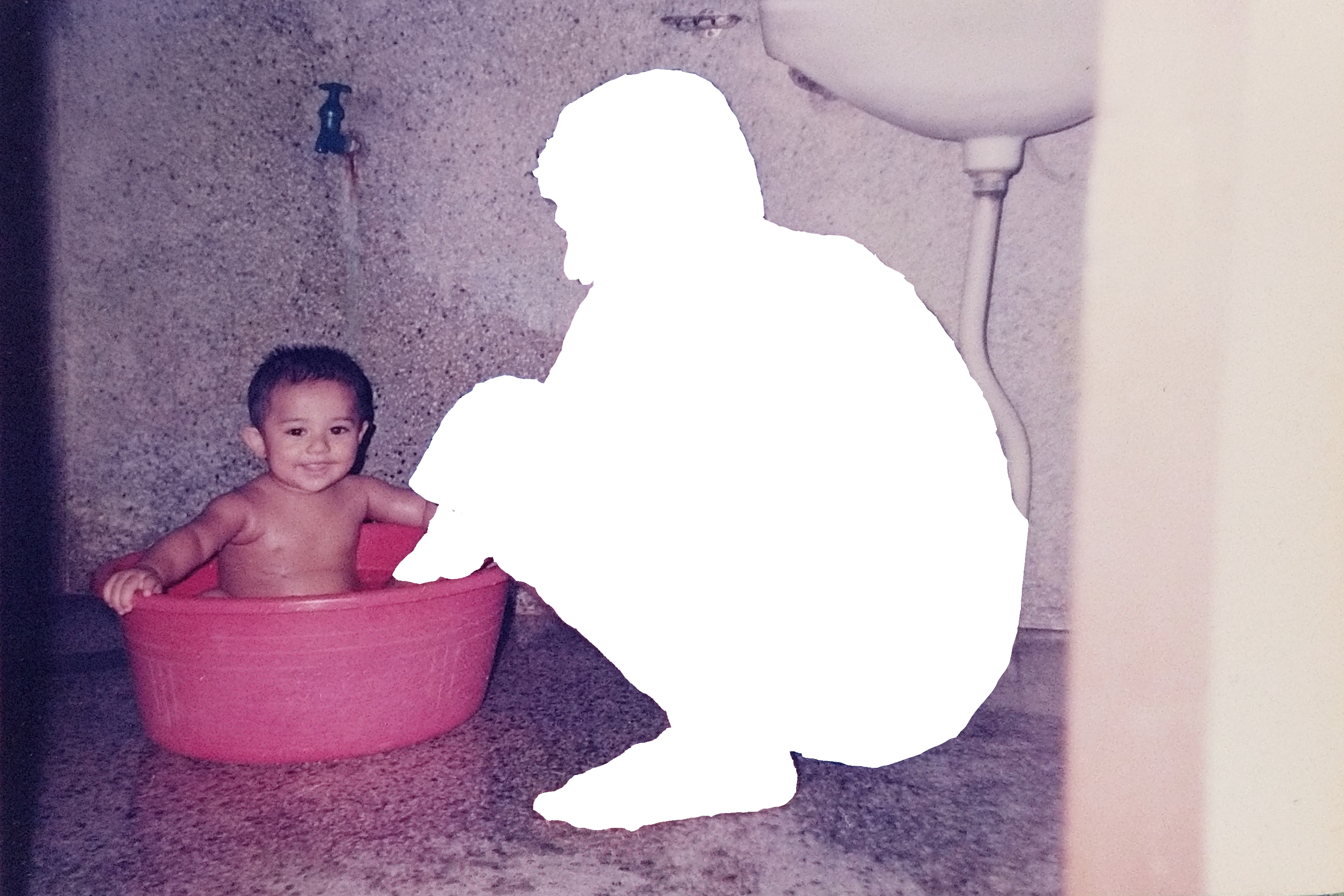

It would have been helpful to have an instruction manual on how to celebrate Eid without my father. I can’t remember if I have ever celebrated Eid without him. It is not that I don’t have a father anymore, but that he is in a jail a few hundred kilometers away. His crime? My father, Shafiqul Iislam Kajol, aged 50, a photojournalist and editor of a newspaper, shared some posts on Facebook! He was missing for 53 days. He was found by police with his hands bound and eyes tied with a cloth. Instead of untying his hands, they handcuffed them and brought him to court. His bail has been denied again and again. One case after another, they are tying him up tightly with the law. I didn’t say anything to anyone, but I thought my father would be released before Eid. I thought my family would get back the peace we lost for over two months.

I perform all the fasting in Ramadan. I did it this time too. I thought I would die before I fasted one day without my father. But I fasted for all 30 days. As far as life goes, our whole family stands together in front of the clock called “Waiting.” The foolish time giving exactly the same time every hour. Foolish clock, we are not friends anymore.

If anyone ever asked what is the most difficult thing in this world, I would have had a lot to answer back then. Is there ever an end to suffering in this world? It’s as if Waiting is written thick on a piece of paper and hung mockingly right before our eyes every moment of every day. My eyes are red. They hurt. My mother’s two eyes are swollen and my sister Poushi’s are numb. All of our eyes are stuck at our front door. If we seldom fall asleep with fatigue, our ears are always alert. Phone ringtones play and our hearts are tied with a wire barrier. Our noses are always on alert. The familiar scent of my father’s existence left behind on his worn clothes has our whole house panting day and night, tricking our senses into thinking maybe he has returned.

There can be nothing as dull as Waiting, nor, at the same time, as sharp. Where all other hardships cut in one direction, Waiting cuts in as many directions as it wants. It goes straight along the middle of the chest and cuts deep for a slow bleed. And Waiting for your father to return home under this pandemic is the hardest of all. No mercy in the bite. The face of Waiting is stained with the wounded blood of the four of us. If you can imagine the hot breath of Waiting on your neck every moment, you would know. But you can only know it if your father is imprisoned like mine for the unforeseeable future.

After the Eid moon rose, I realized my father would not come home. I avoided the dumb question in Poushi’s eyes as long as I could. And if I couldn’t, I kept my head down in shame. It was a shame to look at my mother’s swollen eyes. While looking at the ground, every crack in the floor of our home had become a kind of friendship. I have a few favorite cracks in the floor where I regularly seek refuge for both of my eyes.

We had to celebrate Eid alone this year. That is the only truth now. We only knew how to celebrate Eid with our father, we had no idea what Eid would be without him. We only know now how Eid special Semai feels going down our throats. We left our father’s Semai bowl empty.

Couldn’t the state have given us a little Eid as a greeting? The state is now releasing many convicts from overcrowded jails. My father has not yet been convicted of any crime. So why is his bail rejected every time? Who can I ask to answer this question? At this point, we don’t even want answers anymore. In fact, we just want our father back among us. I want my own life back. I did not want such a life. I know, you can never give me back my life like before. I don’t want a refund, and I didn’t even want an account in the first place. So the only demand is to return my father to us. Let my father sleep in his bed for one day. Just give me one day so that I can breathe a little relief.

The day before Eid, I went to the verandah and sat in the wind. As soon as I opened the door of the house, everything was floating in the very familiar fragrance of Ramadan’s Eid. COVID-19 could not taint that fragrance. Neighboring mothers and aunts were cooking Pulao and Roast in advance for the Eid day at their homes. That nostalgic fragrance would not leave me alone. Through the windows of the neighbors’ flats, I saw a whole family sitting together and talking while my family hung behind inside, all of us hanging on that white rope called Waiting. Time, Mister, you are moving as slow as a tortoise over our living corpses. If I could, like the able families of Bangladesh, I would forget our past two and a half months by smearing red beef broth on white rice.

Father was still in Jessore jail on the day of Eid. As a child, I used to go for walks with my father on Eid days. Jail is not a place to go. For the second time, I went to Jessore ignoring COVID-19, thinking only that I would get my father back. That did not happen. When I was leaving him in the jail, he said, “Abba, you have to do all of this, I don’t like to see you like this anymore.”

The government of Bangladesh locked down the whole country on the 20th of May to save the people from COVID-19, with checkpoints in every district town. I thought Dad would sit next to me and come back with us. I thought a lot while going to Jessore from Dhaka about how I could hold my father’s hand tightly all the way back. But I could not even imagine the warmth of my father’s hand anymore. It had been so long.

On the way back, if you only knew a portion of what happened. What could I tell you? At every district checkpoint, the police stopped our vehicle. Going to the police and soaking wet in the rain, I said, “My father is in Jessore jail, I am returning home to Dhaka after seeing him.” They refused to let us in at the checkpoint in Gazipur. The police did not believe me and told me to park the vehicle on the side of the highway. At that point, I did not have documents from the Jessore court. Even after 15 days had passed, my father was in jail under Section 54. The law of Bangladesh clearly states that no one can be kept in jail for more than 15 days under Section 54. Do you not have an answer?

I am standing on the side of the highway with the vehicle. Rain of cyclone “Ampaner” overhead. The police look on and stare occasionally at me. Many thanks to the rain. At least I did not have to see the police with tears in my eyes.

Somehow I find myself back home at dawn. For some reason, it seems I am still standing alone on that side of the Gazipur highway. The police have been watching me for a while.

By Monorom Polok, June 2020. Polok is the son of Shafiqul Islam Kajol, a Bangladeshi photojournalist currently jailed under likely spurious charges because of his human rights work. Polok launched the campaign, “Where is Kajol?” to find and free his father.

Read PEN America’s statement on Kajol’s arrest here.