Safety Guide for Artists

Artists take risks, but they should not have to risk their lives. Nevertheless, global watchdogs document hundreds of cases each year of artists who are attacked, imprisoned, and even killed for their work––and countless more cases go undocumented.

In response to these realities, the Artists at Risk Connection (ARC) of PEN America has developed A Safety Guide for Artists, a first-of-its-kind manual that offers practical strategies for artists to understand, navigate, and ultimately overcome risk. While such tools have been developed for journalists, human rights defenders, and cartoonists, no guide has been designed specifically for artists. A Safety Guide for Artists fills this crucial gap in providing artists with a resource tailored to their needs.

When an artist first faces risk, there are not a lot of roadmaps: the experience can be incredibly isolating and disorienting. A Safety Guide for Artists explores topics such as defining and understanding risk, preparing for threats, fortifying digital safety, documenting persecution, finding assistance, and recovering from trauma. Tips and strategies were drawn from testimony of artists who have faced persecution, including Cuban performance artist Tania Bruguera, Lebanese singer Hamed Sinno, American visual artist Dread Scott, and Kenyan filmmaker Wanuri Kahiu, as well as the research and expertise of ARC’s vast network of partners.

The guide is available in English, Spanish, and French. Click the “Download PDF” feature at the top of this page to access the pdf versions.

Foreword

One night in October 2019, as a curfew blanketed the city of Santiago, Chile during nationwide demonstrations for social justice, opera singer Ayleen Jovita Romero peacefully protested by singing “El derecho de vivir en paz” (“The right to live in peace”) from her window, a song made famous by singer Victor Jara before he was murdered following the 1973 military coup.

As UN Special Rapporteur in the Field of Cultural Rights, I shared this example in my March 2020 report on cultural rights defenders (CRDs)––human rights defenders who defend cultural rights in accordance with international standards––because this story shows the ways that artists can both challenge injustice and bring hope to others in difficult times. Artists and their work promote access to culture and creative responses in the face of human rights violations and strife. Yet, artists and other CRDs have not been adequately recognized as human rights defenders, and therefore receive insufficient protection when their work puts them at risk around the world.

Over the past few years, I have had the opportunity to collaborate frequently with the Artists at Risk Connection (ARC) on just such issues, jointly hosting expert meetings and public programs and working together along with other partners on advocacy concerning persecuted artists. ARC has also coordinated joint statements with a range of other civil society organizations engaged on these issues at the Human Rights Council in support of the cultural rights mandate. All these activities have made a significant contribution to work on cultural rights in the United Nations system. Through stakeholder meetings that ARC has helped facilitate, they have also played an important role in working to build a coalition of civil society organizations to defend the cultural rights of different constituencies, including women, persons with disabilities, indigenous peoples, minorities, and LGBTQIA+ people. With their wide-ranging understanding of both the human rights and cultural spheres and their intersections, ARC has excellent capacity to be a catalyst for collaboration and to help raise awareness of cultural rights like artistic freedom at the international level.

It is therefore my pleasure to introduce A Safety Guide for Artists, a vital tool to help artists access needed support in the face of threats to their human rights. Similar to analogous guides for journalists and other human rights defenders, this guide affords a critical tool for those working to defend their own right to freedom of artistic expression and that of others.

The field of artist support is constantly evolving, as new programs emerge and as artists continue to be mainstreamed into discussions of defending human rights. This critically important guide offers a window into that field, helping artists develop strategies to overcome persecution.

A great deal of my work as Special Rapporteur has been devoted to understanding the needs of cultural rights defenders and advocating for the steps that should be taken to ensure their safety. In offering a comprehensive toolkit of practical strategies to counter the risks, I am certain that this guide will be crucial in advancing artists’ safety around the world. I also hope it will help bring much-needed attention from governments, international mechanisms, human rights organizations and civil society generally to the threats that artists face, therefore helping to ensure that the next Victor Jara or Ayleen Jovita Romero in any country is able to make their work in peace.

–Karima Bennoune, United Nations Special Rapporteur in the Field of Cultural Rights

Introduction

The year 2020 has exploded with global crises. Even before the COVID-19 pandemic began, the rise of nationalist, authoritarian, and extremist regimes and conflicts around the world led to disturbing increases in violations of fundamental human rights. In response to these threats, massive social movements, from pro-democracy protests in Hong Kong "Hong Kong kicks off 2020 with fresh protests,” BBC, January 1, 2020. to calls for a new constitution in Chile, Philip Reeves, “Protests in Chile,” NPR, January 11, 2020. arose, generating hope for more equitable societies. But these movements also led to ever-greater dangers for activists, frontline workers, and outspoken voices.

The health crisis has only intensified these realities. Beyond placing restrictions on everyday life, from the shuttering of venues and public spaces Valentina Di Liscia, “As the Art World Shuts Down Over COVID-19, Uncertainty Plagues Hourly Workers,” Hyperallergic, March 19, 2020. to the shutdown of borders, “Coronavirus: Travel restrictions, border shutdowns by country,” Al Jazeera, June 3, 2020. authoritarian regimes and declining democracies alike have exploited the pandemic to crack down on dissent. They have curbed protests through enforced curfews, Anthony Faiola, Lindzi Wessel, and Shibani Mahtani, “Coronavirus chills protests from Chile to Hong Kong to Iraq, forcing activists to innovate,” The Washington Post, April 4, 2020. criminalized activism under the guise of vague laws meant to curtail “spreading disinformation” about the virus, “Thai Artist Arrested for Posting About Country’s Coronavirus Screening,” PEN America, March 25, 2020. and more. The pandemic helped quell the protests in Iran Max de Haldevang, “Coronavirus has crippled global protest movements,” Quartz, April 1, 2020. and Iraq to Argentina and Venezuela Faiola, Wessel, and Mahtani. to Hong Kong, Austin Ramzy and Elaine Yu, “Under Cover of Coronavirus, Hong Kong Cracks Down on Protest Movement,” The New York Times, April 21, 2020. where the Chinese legislature slammed through a disturbing national security law “Hong Kong security law: What is it and is it worrying?” BBC, June 30, 2020. that many believe signals the end of Hong Kong’s autonomy and which has already been used to arrest countless outspoken voices. Austin Ramzy, Tiffany May, and Elaine Yu, “China Targets Hong Kong’s Lawmakers as It Squelches Dissent,” The New York Times, November 11, 2020.

And yet, at the same time, to a degree not seen in decades, opposition movements are ascending, from protests of police brutality in the United States Eliott C. McLaughlin, “How George Floyd's death ignited a racial reckoning that shows no signs of slowing down,” CNN, August 9, 2020. to massive demonstrations rejecting the rigged 2020 presidential election in Belarus. “Nearly 3 months after vote, Belarus protests still go strong,” Associated Press, October 31, 2020. Throughout this outpouring of dissent, artists have stood at the forefront, Carly Mallenbaum, “Art activism: Stories behind murals, street paintings and portraits created in protest,” USA Today, July 6, 2020. bearing witness to inhumanity and catalyzing solidarity through songs, Marta Balaga, “Las Tesis, Collective Behind Anti-Rape Protest Song, on Campaign Against Violence,” Variety, October 31, 2020. slogans, Aliaksandr Bystryk and Karolina Koziura, “Strategies of Protests from Belarus,” Public Seminar, November 9, 2020. and murals Raisa Bruner, “'Art Can Touch Our Emotional Core.' Meet the Artists Behind Some of the Most Widespread Images Amid George Floyd Protests,” TIME, June 3, 2020. that call for change. When artists are able to express themselves freely, they can be forceful and influential voices that document oppression, articulate cultural critiques, and accelerate social progress. Art can offer an essential outlet for nurturing free thought and exercising free will. It can help independent viewpoints survive, challenge orthodoxies in ways both subtle and overt, and create openings that allow citizens to imagine a different future.

But this power can also put artists at the forefront of backlash, exposing them to violence, intimidation, and other forms of persecution by both governments and non-state actors. It is no accident that artists are among the first targets for suppression during the rise of authoritarian regimes, the spread of armed conflicts, and the collapse of democracies.

In 2019, the Artists at Risk Connection (ARC) received more requests for assistance than in any previous year, and global watchdogs documented over 700 incidents in at least 93 countries in which artists’ rights were violated "The State of Artistic Freedom 2020," Freemuse, April 15, 2020.—numbers that do not include hundreds of cases that go unreported. While many artists defy these attacks and continue their work, others live in constant fear for their safety and the safety of their families, and some have been intimidated into self-censorship or silence. Though many threats come from state actors such as governments, politicians, police, and the military, they can also come from non-state parties, including extremist groups, fundamentalist or conservative communities, and even one’s own neighbors and family members. These attacks rob artists of the opportunity for creative expression and impoverish democratic discourse by excluding challenging ideas and perspectives and depriving the public of valuable contributions, insights, and inspiration.

Artists are vital to the health and longevity of free and open societies, and their importance is enshrined in international law. “Artistic expression,” as former UN Special Rapporteur in the Field of Cultural Rights Farida Shaheed has stated, “is not a luxury, it is a necessity.” Farida Shaheed, “The right to freedom of artistic expression and creativity,” UNESCO, March 14, 2013. As a fundamental human right, it is addressed in varying ways in a number of documents within the international human rights framework, including article 27 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights; “Universal Declaration of Human Rights,” OHCHR, 1948 article 15 of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights; “International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights,” OHCHR, 1966 and related provisions of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. It is also addressed by UN Special Rapporteurs in the field of cultural rights and freedom of expression; as outlined in the Special Rapporteur in the Field of Cultural Rights’ 2020 report, artists are cultural rights defenders––those human rights defenders who act in defense of culture––and therefore deserve the same recognition and protection as traditional human rights defenders. Karima Bennoune, “Cultural rights defenders. Report of the Special Rapporteur in the field of cultural rights,” pp. 3-4, OHCHR, 2020 and OHCHR, “Who is a defender?” Artists take risks, but they should not have to risk their lives.

What is ARC?

The Artists at Risk Connection, a project of PEN America, aims to safeguard the right to artistic freedom of expression and ensure that artists everywhere can live and work without fear. ARC works to achieve this goal primarily by connecting persecuted artists to our growing global network of resources, facilitating cooperation among human rights and arts organizations, and amplifying the stories and work of at-risk artists. ARC plays the role of connector and coordinator, matching need and response to equip artists with the means to withstand pressure and continue creating.

Since its inception in 2017, ARC has assisted more than 261 individual artists and cultural professionals from over 61 countries by connecting them to a wide range of services, most frequently including emergency funds, legal assistance, temporary relocation programs, and fellowships. Thanks to a core network of over 70 partners, over 50 percent of artists who seek our help have already received direct support. Our network is the heart of ARC: Since we are not a direct service provider but a hub that brings together the vast constellation of organizations that support artists, our work would not be possible without the diverse partners we refer artists to.

You can contact ARC through our website, via email at arc@pen.org, or via our encrypted intake form. For more information about using ARC’s resources, please refer to the “Finding Assistance” section.

Why Does This Guide Exist?

In the four years since ARC was created, we have been fortunate to collaborate with a vast array of partners working on the ground to support artists at risk. We have engaged an even larger number of organizations that might not traditionally have supported artists but are now beginning to serve them, such as Freedom House, Front Line Defenders, and ProtectDefenders.eu. However, while a number of robust guides exist for vulnerable journalists, “Safety Guide for Journalists,” Reporters Without Borders and UNESCO, 2015. cartoonists, “Practical Guide for the Protection-of Editorial Cartoonists,” Cartooning for Peace, 2019. and human rights defenders, See “New Protection Guide for Human Rights Defenders,” Protection International, 2009 and “Protection Guide for Human Rights Defenders,” Front Line Defenders, 2005. and other vulnerable groups, Gary McLelland and Emma Wadsworth-Jones, “Humanists at Risk: Action Report 2020,” Humanists International, 2020. no such tool exists expressly for at-risk artists.

In creating this manual, ARC aspires to offer concrete recommendations and provide a comprehensive tool kit to help artists navigate, counter, and overcome threats and persecution. This guide will cover topics including cybersecurity threats and best practices; tactics used by governmental and non-governmental actors to attack artists; resources available to artists under threat and ways for organizations to provide support; methods of identifying risks to yourself; strategies for developing a safety net and plan; actions to take against perpetrators; and an appendix of further resources.

Although ARC has tried to make this manual exhaustive, every experience of risk is unique, and this guide may not provide every tool for every scenario. In such cases, we recommend getting in touch with ARC or with one of the vast array of organizations that might be able to meet your specific needs with specific assistance, many of which are listed in the appendix. Because the world changes quickly, we will give frequent updates to keep this information relevant. In particular, the COVID-19 pandemic has caused massive disruptions in the field of artistic freedom. Some of the resources recommended in this guide may currently be on hiatus or be offering altered services. We always recommend checking organizations’ websites directly to get the most up-to-date information regarding their support.

This guide has been inspired by the practical experience of ARC and our partners. In compiling it, we have listened to artists themselves—their direct requests for assistance, their responses to a survey that we conducted in 2018, and their thoughts expressed in in-depth interviews that we conducted in 2020. We have also drawn on research and manuals published by organizations that specialize in assisting artists, journalists, and human rights defenders. Certain sections might act as a gateway to other organizations’ resources, to which we have provided useful links or footnotes.

This guide will be continually updated as trends and recommendations change.

We hope that by presenting the voices of artists who have faced similar challenges and the strategies they used to overcome them, this guide can help at-risk artists feel less alone, more prepared, and better able to make their art in peace.

Special Thanks

This guide would not exist without the continued, crucial support of the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, ARC’s primary funder; the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts; the Elizabeth R. Koch Foundation; the Silicon Valley Community Foundation; and the Taiwan Foundation for Democracy. We are immensely grateful to them for helping ARC make the world a safer place for artists.

Methodology

With our bird’s-eye view of the field of available resources, ARC developed this guide by drawing upon the wealth of expertise of our global partners and PEN chapters and upon information gleaned from the 280 artists ARC has helped connect to direct support, 197 responses to a survey of persecuted artists conducted in 2018, and 13 interviews conducted in 2020 with prominent artists who have experienced persecution.

Global Network

ARC strives to act as a clearinghouse, bringing together the vast constellation of global resources for artists at risk into one accessible hub. Before its existence, artists in need and their allies would have to peruse hundreds of individual websites to search the scope of existing resources. With ARC’s database, all of these resources are compiled in one portal. When ARC was launched in 2017, its network included 709 partner organizations—579 in its public, searchable database and 130 in a private database offering resources to persecuted artists. As of October 2020, the network has grown to 881 partners, including 673 in the public database. Of these organizations, about 70 constitute ARC’s core network—partners that ARC consistently turns to and collaborates with when aiding artists at risk. In addition to its global network, ARC has an Advisory Committee made up of prominent artists and representatives of core partners. This wide range of partners gives ARC a unique opportunity to study the field of artist support as a whole and understand what services exist, which are most helpful, and how artists can most effectively navigate them.

Much of this manual draws upon the insights, expertise, research, and resources of this diverse group of partners. Partners regularly conduct research and publish reports, many of which have been cited throughout this manual. In addition to collaborating on assisting at-risk artists, ARC regularly works in concert with our partners when attending international forums and hosting public and private programs—giving us insights into how service-providing organizations operate, which trends and challenges are most salient, and which organizations are best equipped to provide support to artists in need. This guide, and ARC’s work, would not be possible without their knowledge.

Requests for Assistance from Artists at Risk

Since its inception, ARC has received 261 requests for assistance from artists in 61 countries, and we work daily to refer these artists to our partner organizations. By analyzing trends in these requests, ARC has gained a deeper understanding of the state of artistic freedom and has been able to make inferences that helped inform the contents of this guide. But the requests that ARC receives by no means capture the full scope of persecution faced by artists. Though ARC receives about 87 requests a year, research from our partners and other watchdogs suggests that hundreds, if not thousands, more artists face substantial threats.

2018 Survey of Artists at Risk

To complement and deepen the information that ARC has gleaned from the artists who contact us, in 2018 we surveyed 197 individual artists at risk globally to better understand their needs, conditions, and challenges. This survey explored questions about what types of risk artists perceive, what risks they have experienced, and how often they have experienced them. It also asked artists about their views of the assistance process, perceived gaps in available support, regions where risk is most acute, and more. The survey provided crucial data that has helped ARC better understand the worldwide landscape of threats and support.

In addition to general biographical questions, the main questions of the survey included:

- What do you feel is the biggest threat to freedom of artistic expression?

- Have you experienced persecution as a direct result of your work as an artist?

- To the best of your knowledge, who are/were the perpetrators of the persecution?

- To the best of your knowledge, what is/was the reason for the persecution?

- What action(s) did you take or are you currently taking to protect yourself?

- What kind of support, if any, did you receive, or are you receiving?

- When persecuted, what was/is the best way for you to access information about support?

2020 Interviews Conducted with Artists at Risk

Each of ARC’s in-depth interviews with 13 prominent artists who have previously been or are currently at risk lasted approximately one and a half to two hours and explored the artist’s career, activism, and experiences coping with persecution and finding assistance. Conducting firsthand interviews enabled ARC to ascertain what the lived experience of risk is like, what tactics artists use to counter threats, what forms of support help most, and what forms of support remain lacking.

ARC interviewed the following artists:

- Aslı Erdoğan, Turkish writer

- Betty Tompkins, American painter

- Dread Scott, American visual artist

- Hamed Sinno, Lebanese singer

- Kubra Khademi, Afghan performance artist

- Masha Alekhina, Russian member of art collective Pussy Riot

- Nanfu Wang, Chinese documentary filmmaker

- Oleg Sentsov, Ukrainian filmmaker

- Shahidul Alam, Bangladeshi photographer

- Tania Bruguera, Cuban performance artist

- Valsero, Cameroonian rapper

- Wanuri Kahiu, Kenyan filmmaker

- Yulia Tsvetkova, Russian visual artist.

The main interview questions included:

- Can you tell me about your development and career as an artist? As an activist? At what point did you realize these two were connected?

- When did you first experience risks, threats, harassment, persecution, etc., as a result of your creative approach? How have the threats intensified over your career as you continued to make artwork?

- How did threats/persecution affect your creative practice? How were your life and career affected?

- When threats began, please walk me through what you did to find assistance. Did you reach out to other members of the art or activist community, or elsewhere, such as human rights groups?

- If you did receive assistance from a human rights organization, can you discuss what it was like to navigate the world of human rights support as an artist? What was your experience in turning to the art community for help?

- What advice would you offer to other artists who are put at risk because of their artwork/activism for the first time?

For more about each artist, see the “Artists’ Voices” section of this manual.

Patterns of Persecution

Throughout ARC’s existence, the number of requests for assistance from at-risk artists has continuously grown. While this growth is partly due to increased awareness of ARC’s resources, we believe it is also rooted in the global rise of authoritarian, nationalist, and extremist regimes and groups that are exerting pressure on artistic freedom of expression. The COVID-19 pandemic has only exacerbated such threats.

Although artists from all over the world contact ARC for assistance, the majority come from the Global South, and from a few regions in particular. Year after year, since ARC’s inception, the most requests—42 percent—have come from the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region, followed by artists from Africa (19 percent), Latin America (14 percent), and Asia (11 percent), with other regions constituting the remaining 14 percent of requests. Within these regions, certain countries tend to have higher rates of violations of artistic freedom than others. For example, while many countries have only one to two artists a year who reach out for support, ARC has received 36 requests for assistance from Iranian artists, nearly 14 percent of the total number of requests. Other high numbers come from Turkey (19), Egypt (17), Cuba (15), and Yemen (11).

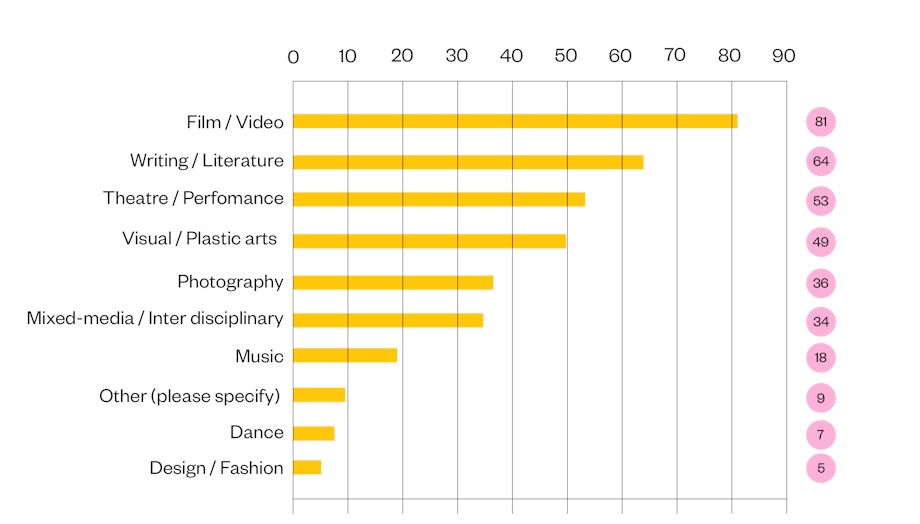

In terms of artist disciplines, ARC receives the most requests from visual artists (a category that encompasses anyone working in a visual medium, including painters, filmmakers, and photographers), at 38 percent, followed by writers (28 percent), musicians (13 percent), and other cultural professionals such as curators, theater directors, art scholars, and researchers (10 percent).

Requests for assistance overwhelmingly come from artists who identify as male—only 28 percent of ARC’s cases have been imperiled women—partly because male artists are more likely to self-report risk and seek assistance. Yet while female and non-gender-conforming artists make up only a small percentage of ARC’s cases, the risks they experience tend to be greater in severity and related to their gender in some capacity, which is not typical for male artists’ persecution. Furthermore, threats tend to more significantly affect artists who identify with minority groups, whether due to their gender, sexuality, language, ethnicity, religion, race, or class.

Thirty-two percent of artists who contact ARC for assistance do so because they are experiencing threats of violence, death, verbal or physical harassment, or arrest, followed in frequency by artists who have already been arrested or detained and are looking for assistance either to avoid imprisonment or to be released from prison (22 percent). Artists seeking asylum assistance and/or looking for support in exile also make up a substantial portion (13 percent) of ARC’s requests.

When ARC receives such requests, we assess the situation and level of risk and connect artists to the support they need. ARC does not provide direct services but rather refers artists to our global network of partner organizations, each of which has its own parameters for what it can provide and how many cases it can take on. Twenty-nine percent of ARC’s requests have come from artists seeking to flee threats by relocating to a safer area, either temporarily within their country or region or long-term, often to countries in the Global North. Requests for relocation tend to come alongside those for emergency grants, often to pay travel costs, or living costs after relocation. Although some urgent funds are earmarked specifically for artists, many tend to be restricted to extremely prominent artists seeking to carry out specific creative projects and are only rarely reserved for those in dire need. Instead, ARC must often connect at-risk artists to emergency grants for human rights defenders, offered by a wide range of human rights organizations around the world.

Requests for relocation and emergency grants are followed in frequency by requests for legal assistance (such as representation in a criminal case, immigration advice, and trial monitoring) and for advocacy (help with raising awareness about their situation and putting pressure on governments, institutions, or other perpetrators). More often than not, however, artists request a mix of services: They may need relocation assistance as well as funds to support them abroad, or they may need public advocacy in addition to publishing opportunities to boost visibility of their case.

After artists receive support, ARC stays in touch with them to ensure the long-term sustainability of their safety, as they often find themselves bouncing from one resource to another, their threats persistent and ongoing rather than singular, one-off experiences. Beyond direct persecution, artists often endure continuing difficulties related to psychological and emotional trauma. So lasting security often requires long-term cooperation with organizations or a combination of short-term opportunities in succession.

Section I: Defining Risk

Art is inherently political. Through creative work, artists use image, representation, metaphor, motif, and more to challenge the status quo, oppressive religious beliefs, reigning political ideologies, social and cultural norms, and moral or economic injustices. Artists don’t always make an active choice to be political; often they do so unintentionally when their work unexpectedly touches on sensitive topics. Yet engaging politics, deliberately or not, can be one of the most dangerous acts of their career. Because art has the power to move people and envision alternative, more equitable societies, artists often face significant threats from those seeking to silence them. These threats include censorship, verbal or physical harassment, assault, arrest, legal prosecution, imprisonment, torture, and even death.

Whether or not you affirmatively decide to be politically engaged and make overtly political art, it is important to understand the kinds of risks faced by artists around the world. Such awareness is crucial to knowing how and why your own work might put you at risk and will leave you better equipped to anticipate, withstand, and ultimately overcome pressure.

What Kinds of Threats Do Artists Face?

Artists can face a wide range of risks around the world. The following are the most common:

Censorship

The enforced silencing of artists—by preventing them from displaying or promoting their work, forcing them to alter its content, or damaging or destroying it—is far and away the most common threat worldwide. “The State of Artistic Freedom 2020,” Freemuse, April 15, 2020. Censorship can be carried out by both state and non-state agents, through laws and regulations, corporate and commercial pressures, or force and intimidation. Many countries require artists to get licenses from a censorship board to make art. State-sponsored censorship is often carried out on such grounds as protecting national security, “Censorship and Secrecy, Social and Legal Perspectives,” MIT, 2001. controlling obscenity, “Definitions of Censorship,” PBS. regulating hate speech, “Free Speech and Regulation of Social Media Content,” Federation of American Scientists, March 27, 2019. promoting or restricting political or religious opinions, “Censorship and Secrecy, Social and Legal Perspectives,” MIT, 2001. and preventing libel. “First Amendment and Censorship,” American Library Association, October 2020. But censorship may or may not be legal, and many countries have laws that protect against it.

In the internet age, censorship on digital platforms by both private and public groups is another growing concern, as authoritarian regimes control what content is allowed online "About Democracy in the Digital Age,” Pew Research Center, February 21, 2020. and social media companies use arbitrary algorithms to remove content deemed inappropriate. See “Internet,” National Coalition Against Censorship. Furthermore, censorship begets censorship, and many countries have cultures of self-censorship, a toxic situation in which fear of censorship or retaliation leads artists to muzzle themselves. David Kaye, “Disease pandemics and the freedom of opinion and expression,” OHCHR, July 24, 2020, p. 11.

In Kenya, filmmakers are required to get approval from a censorship board before they can make and distribute their films. When Wanuri Kahiu, a world-renowned filmmaker, brought her film Rafiki to the Kenya Film Classification Board, she was asked to make a few changes. The film, about two young girls who fall in love, was viewed as too pro-LGBTQIA+ in a country where homosexuality is still criminalized. But Kahiu refused to censor her film, so it was banned. Besides a one-week release period after Kahiu appealed, and in the face of international acclaim, Rafiki has not been available in Kenya. Cobie-Ray Johnson, “Wanuri Kahiu,” Artists at Risk Connection, 2020. Read more about Kahiu’s case in the “Artists’ Voices” section.

Detention, Legal Prosecution, and Imprisonment

Detention, prosecution, and imprisonment are the second-most-frequent violations of artistic freedom. “The State of Artistic Freedom 2020,” Freemuse, April 15, 2020. Detention occurs when an artist is arrested and taken to jail but has not yet been charged with a crime. As soon as an artist is indicted for a crime, prosecution begins. Artists who are successfully prosecuted and convicted may be sentenced to prison or face some other punishment. Artists can be arrested, prosecuted, and imprisoned for a wide variety of reasons. Often such actions are politically motivated, but sometimes they are legitimized under existing statutes and laws. To understand what kind of laws you could be prosecuted under, see “Knowing Your Country’s Laws.”

Egypt is one of the world’s most frequent jailers of artists and writers. "Freedom to Write Index 2019," PEN America. One of the most common tactics used by President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi’s government to silence artists and other dissidents is pretrial detention, which allows detainees who have been arrested, but have not been formally charged or undergone trial, to remain in custody for up to two years—a limit that is often violated. “60+ Organizations Call for Release of All Artists, Writers, and Journalists in Pre-Trial Detention in Egypt,” Artists at Risk Connection, 2020. On May 2, 2020, after spending 793 days in pretrial detention for filming a music video that was critical of el-Sisi, 24-year-old filmmaker Shady Habash died in jail. Declan Walsh, “Filmmaker Who Mocked Egypt’s President Dies in Prison,” The New York Times, May 2, 2020. Not long after, a friend, film editor Sanaa Seif, was also placed in pretrial detention. Her brother, prominent activist Alaa Abd El Fattah, was already behind bars in pretrial detention at the time. “World renowned actors, filmmakers, and writers call on Egypt to release Sanaa Seif,” Artists at Risk Connection, August 4, 2020.

Harassment, Violence, and Assault

Artists around the world can face generalized harassment, including physical violence and assault; online abuse; verbal hate speech or threats carried out in person, by phone, or on digital platforms; physical assault such as beatings, police raids, or damage to facilities and equipment; state violence, including torture; and even killings or death sentences.

Sanctions and Fines

Artists are frequently subject to fines and sanctions, which act as a sort of extension of censorship. Governments try to force artists to be silent by levying heavy fees against them for a wide range of reasons, from violating minor laws and committing petty infractions to imposing sentences related to criminal or civil prosecution. Polina Sadovskaya, “Kirill Serebrennikov,” Artists at Risk Connection, e.g.

Travel Bans

State persecution often goes hand in hand with travel bans. When a state seeks to criminalize an artist, it will often place them under a travel ban or even house arrest for the duration of their court case—and longer still if they are handed a conviction. These tactics are meant to constrain an artist’s ability to spread their work across borders and cultures, seek safety in a third country, and meaningfully advance their career through international opportunities.

In Russia, travel bans are frequently used against artists currently on trial or under investigation. In 2017 Kirill Serebrennikov, a prolific Russian playwright and theater director, was detained and charged with embezzling 68 million rubles, a politically motivated and spurious allegation meant to silence a prominent critic of Putin’s regime. He was placed under house arrest from August 2017 to April 2019, when he was released on bail. On June 26, 2020, he was convicted and received a suspended sentence, and although the case has now concluded, he remains unable to leave Russia, causing lasting damage to his ability to engage foreign arts institutions and communities. Sadovskaya, Artists at Risk Connection.

Who Is Most Vulnerable To Threats?

While any artist can be put at risk for their work, certain factors increase the likelihood that this will occur. Women, LGBTQIA+ people, those with disabilities, seniors, migrants or refugees, and members of religious, ethnic, or linguistic minorities often find themselves at heightened risk of repression, as do artists in the world’s most restrictive regions.

Women and LGBTQIA+ People

Though male artists tend to make up more documented cases of risk, women and non-gender-conforming artists face a greater range of threats related to their gender than their male colleagues. ARC Case Data. Also see ““Safety Guide for Journalists,” Reporters Without Borders, 2015, p. 14. This occurs for a variety of reasons, including orthodoxies and regulations about gender and sexuality, regressive social attitudes toward women, and heightened risks of sexual violence. The same holds true for members of the LGBTQIA+ community. Even if their work is not explicitly related to their sexuality or gender, hostile attitudes and biases toward these groups place them at inherently higher risk.

Russian feminist artist and activist Yulia Tsvetkova is currently on trial for disseminating pornography, a charge that could land her in prison for up to six years. Her only crime was making pro-LGBTQIA+ and body-positive artwork. After creating two social media webpages that displayed work by feminist artists, some of which included frank depictions of female genitalia, Tsvetkova was arrested in November 2019 and charged in January 2020. In a society in which “gay propaganda” is outlawed and in which homophobia and misogyny are rampant, Tsvetkova’s case was largely seen as punishment for raising taboo subjects. Annie Kiyonaga, “Yulia Tsvetkova,” Artists at Risk Connection, June 2020.

Minorities or Underrepresented Groups

Sometimes merely being a member of a minority or underrepresented group can lead to persecution. Kurds in Turkey and Iran, “Cultural policy effects on freedom of the arts in Turkey,” Index on Censorship, February 13, 2014. Tamils in Sri Lanka, See “Tamils,” Minority Rights Group International. Rohingya in Myanmar, See “Rohingya emergency,” UNHCR. Palestinians in Israel or occupied Palestine, See “Palestine,” Minority Rights Group International. and Uyghurs, Allisen Lichtenstein, “Xinjiang: The Free Expression Catastrophe You Probably Haven’t Heard Of,” PEN America, August 17, 2018. Tibetans, Tsering Woeser, “Tibet on Fire: Self-Immolation Against Chinese Rule,” PEN America, December 30, 2015. and Hui Ibid. in China are among the ethnic and religious minorities, stateless groups, unrecognized people, or otherwise minoritized groups that face persecution.

In the name of combating “Islamist extremism,” the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has turned Xinjiang, an autonomous region in western China, into a police state, where those who publicly express their ethnic identity are marked as potential enemies of the state. Uygher people, a Turkic, Muslim-majority group that makes up about half of the region’s population, are especially vulnerable. According to estimates, more than a million Uyghers are believed to have been detained in “reeducation camps” for “deradicalization.” Lichtenstein. Detainees are not given a trial, a lawyer, or any semblance of due process. Even more shocking, Uyghurs and others are sent to the camps for everyday expressions of their culture or faith. Artists who in any way express Uygher cultural identity—or artists who simply are Uygher—are often detained. Rashida Dawut, a celebrated Uygher singer, was sentenced to 15 years in prison for alleged “separatism” in a secret trial in late 2019, “Prison Sentence for Uyghur Singer Part of China’s Efforts to Eradicate Uyghur Culture,” PEN America, March 27, 2020. and countless Uygher artists, poets, and activists have been similarly persecuted.

Artists From Certain Regions

Artists around the world face risks, but some regions violate artistic freedom more regularly and brutally than others. While some of this variation can be attributed to discrepancies like a lack of reporting or lack of civil society support, it is nevertheless important to recognize that certain threats tend to occur at higher rates in certain regions. The MENA region consistently ranks as one of the highest violators of artistic freedom across a number of metrics, followed by Asia and Europe as the second- and third-most-risky places for artists. See ARC data on types of assistance requested by region from 2018-2020 in “Patterns of Persecution.”

But regional differences shift depending on the specifics. For instance, Europe is one of the most common places for threats based on minority backgrounds. Freemuse 18. And in 2019, the majority of imprisoned writers—141 out of 238 cases—were in just three countries: China, Saudi Arabia, and Turkey. "Freedom to Write Index 2019," PEN America.

Belarus is often labeled the “last dictatorship in Europe.” Its government exerts widespread control over the cultural sphere, supporting official programs that serve its ideological needs and cutting off funding for those that don’t. In early 2020, numerous activists and writers were tried for participating in demonstrations calling for independence from Russia’s influence. Polina Sadovskaya, “Belarus Approaches Another Undemocratic Election, as Arts and Culture Remains Underground,” PEN America, July 27, 2020. Following massive protests in the wake of President Aleksandr G. Lukashenko’s reelection in August 2020—an election widely viewed as rigged—writers, members of PEN Belarus, “PEN America Calls for the Immediate Release of PEN Belarus Members and Employees,” PEN America, September 8, 2020. members of the art collective Belarus Free Theater, “PEN America Demands Release of Three Belarusian Theater Company Members,” PEN America, August 11, 2020. and countless other dissident artists have felt the brunt of the government crackdown, facing arrest and detention. “PEN America Deeply Alarmed Over Belarus Election Crackdown,” PEN America, August 10, 2020.

Where Are Threats Most Likely to Come From?

Threats can come from a variety of sources. The most common are states and state entities, Freemuse, ARC Data. while non-state groups, corporate or commercial entities, and other sources also present risks.

State Groups

State groups, including governments, heads of state, politicians, police, and the military, are by far the most likely entities to persecute artists, who are frequently imprisoned for criticizing government policies and practices. According to data from ARC’s 2018 survey, state agents are by far the most likely group to persecute artists, with 70% of those surveyed indicating that the government was the primary perpetrator, and 32% citing police. Also see Freemuse 13. Artists whose work directly engages political or social issues should prepare for possible retaliation. Those who criticize heads of state are frequently prosecuted for criminal defamation and sued for libel, even if the criticism is valid or warranted. But “apolitical” art can also pose a threat to the status quo, and artists should always be prepared for the possibility of state persecution, including by familiarizing themselves with laws used against artists, as outlined below.

Valsero, one of the most popular musicians in Cameroon, is known for politically tinged rap songs that call for greater accountability and transparency from President Paul Biya’s administration and that strive to spread awareness of civil and political rights. Biya, who has ruled since 1982, has maintained power through decades of intimidation and force, and his regime has taken countless measures to curtail freedom of expression. Over the years, Valsero has been detained a number of times by Cameroonian police forces, and many of his concerts have been banned. On January 26, 2019, he was arrested on the outskirts of a demonstration protesting the previous year’s presidential election, which many Cameroonians saw as rigged to favor Biya. He spent nine months in jail, awaiting trial for charges that carried punishment as severe as the death penalty, until he was eventually released. Anna Schultz, “Valsero,” Artists at Risk Connection, October 2019. For more information on Valsero’s case, see the “Artists’ Voices” section of this guide.

Non-State Groups

Non-state agents such as terrorist and extremist groups, paramilitaries, organized crime, religious fundamentalists, and online trolls and hackers have also persecuted artists. Those whose work pushes against orthodoxies may be more likely to experience the wrath of non-state agents if they live in especially conservative or traditional societies. Similarly, artists in conflict zones may face backlash from armed or extremist groups, and in such cases the availability of traditional legal recourse can be slim. Trolls and hackers may seek to harass artists online or compromise their digital security. Artists can also face attacks from family members, neighbors, and other artists within their own communities.

Sharmila Seyyid, an internationally acclaimed novelist and activist from Sri Lanka, has dedicated her life to advancing gender equality and fighting extremism within her Muslim community. In November 2012, after an interview on BBC Tamil in which she said that legalizing sex work would better protect workers, Seyyid rapidly became a target of vitriolic criticism, harassment, and death threats from religious fundamentalists. Since then, she and her family have faced incessant attacks, including threats of acid assaults and rape. Not long after the BBC interview, the English academy that she ran with her sister was vandalized. In 2019, authorities notified Seyyid that she was a target of National Thowheeth Jama'ath (NDJ), a militant Islamist group responsible for bombings that took place on Easter Sunday in 2019, forcing her to go into exile. Mabel Acosta, “Sharmila Seyyid,” Artists at Risk Connection, May 2020.

Corporate or Commercial Entities

Corporate or commercial entities often censor broadcasters, publishers, communications companies, and other media that have political or social agendas. Shaheed 10. They may also target or harass artists. Broadcasters and media companies that are de facto mouthpieces for the government sometimes use their megaphones to spread disinformation or launch smear campaigns against artists.

Social media platforms present both opportunities and risks for artists, enabling them to amplify their messages while also leaving them vulnerable to persecution. These platforms are among the most common forums for harassment, as trolls and other hostile groups can easily single out artists with vitriolic or threatening speech. Online Harassment Field Manual, PEN America. Artists also face internal censorship, as vague content regulation mechanisms based on “standards of behavior” are open to interpretation, especially regarding hot-button subjects like terrorism and nudity. “The Weekly Takedown,” Online Censorship, November 30, 2016. Women, queer, and transgender artists in particular have fallen prey to such content controls. “Censored Artists and their Stories”, National Coalition Against Censorship.

Knowing Your Country’s Laws

Artists in any situation, regardless of whether they anticipate risk, can benefit from a comprehensive understanding of their country’s speech laws or other legislation that is used against artists.

Logically, laws that regulate speech or expression are most likely to be used against artists thought to have crossed a line, so staying informed about the general climate and current status of free speech and expression is crucial to practicing your art safely. But artists can also be prosecuted under laws with seemingly no connection to art and expression. Laws to pay attention to, if they exist in your country, include, but are not limited to:

Laws Regulating Speech

Many countries have laws that regulate varying forms of speech and expression. These laws usually center on defamation and libel, “Defamation, Libel and Slander: What are my Rights to Free Expression?” Canadian Journalists for Free Expression, June 15, 2015. disinformation, Lian Buan, “Bayanihan Act's sanction vs 'false' info the 'most dangerous',” Rappler, March 29, 2020 and “Egypt sentences activist for 'spreading fake news',” BBC, September 29, 2018, e.g. cybercrime, “Thailand: Cyber Crime Act Tightens Internet Control,” Human Rights Watch, December 21, 2016, e.g. online speech, Brad Adams, “Bangladesh’s draconian Internet law treats peaceful critics as criminals,” Human Rights Watch, July 19, 2019, e.g. and broadcasting and telecommunications. “Burma: Letter on Section 66(d) of the Telecommunications Law,” Human Rights Watch, May 10, 2017, e.g. Speech-related laws are frequently used to criminalize artists for both the content of their work and the views they express. Artists working in countries that deploy such tactics should be especially wary of airing opinions on social media and in other digital spaces.

In Bangladesh, the draconian Digital Security Act (DSA)—formerly the Information and Communication Technology Act (ICT)—is frequently used to criminalize online dissent. With its vague definitions and heavily punishable, non-bailable offenses, the act gives Bangladeshi authorities unprecedentedly wide purview to crack down on freedom of expression and launch investigations into anyone whose activities and/or online speech is deemed harmful or threatening. Under the DSA and former ICT, thousands of Bangladeshi artists, journalists, and activists have been arrested. “Bangladesh: New Digital Security Act is attack on freedom of expression,” Amnesty International, November 12, 2018.

Anti-Terrorism

Along with legislation that regulates speech and expression, governments increasingly turn to anti-terrorism laws to crack down on artists. At least eight countries have used anti-terrorism and/or anti-extremism legislation against artists. Freemuse 17. In over half of such prosecutions, the artists belonged to a minority group. Ibid.

In Turkey, almost any action related to Kurdish identity or language runs the risk of being criminalized under counterterrorism regulations. “Cultural policy effects on freedom of the arts in Turkey,” Index on Censorship, February 13, 2014. When artists represent Kurdish life in their work, the government often invokes the Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK), a militant separatist group, branding them as terrorists even if their art in no way advocates violence or even addresses the political status of Kurds. Zehra Doğan, an influential journalist and artist, was sentenced to prison for terrorism after painting a scene based on a photograph of Turkish troops leveling a Kurdish town. Ben Ballard, “Zehra Doğan,” Artists at Risk Connection, August 2017. Likewise, members of Grup Yorum, a musical collective that often advocates for Kurdish rights and uses the Kurdish language in its songs, have been perennially arrested and convicted under trumped-up terrorism charges. Revantika Gupta, “Grup Yorum,” Artists at Risk Connection, November 2019.

Entertainment Control

Another form of legislation that’s commonly used to target artists is entertainment control acts. In their most drastic form, these laws exist in countries with state censorship apparatuses, such as China “China Media Bulletin: China’s Growing Cyber Power, Entertainment Crackdown, South Africa Censorship”, Freedom House. and Iran. Unveiled: Art and Censorship in Iran, Article 19, September 2006. In these countries, anyone who hopes to create something that could qualify as entertainment—pretty much anything in the cultural sphere, including films, TV, songs, and books—must first submit it to a censorship board, which grants licenses to release the work. If the board deems the content inappropriate or not in line with state narratives, it will withhold the licenses, and if artists circumvent such licenses and make their art anyway, they may face severe threats like imprisonment.

Decree 349 in Cuba, enacted in 2018, institutionalizes and expands limits on creative expression. The decree criminalizes unregistered artistic labor, granting authorities wide remit to censor and constrain artists’ activities. Under Decree 349, there has been an immense uptick in the censorship, harassment, and arrest of independent artists in Cuba. “Art under Pressure: Decree 349 Restricts Creative Freedom in Cuba,” Artists at Risk Connection & Cubalex, March 4, 2019. Since 2017 Luis Manuel Otero Alcántara, an esteemed performance and street artist, has been arrested at least 21 times, frequently as a direct result of his outspoken criticism of the decree. Annie Kiyonaga, “Luis Manuel Otero Alcántara,” Artists at Risk Connection, April 2020.

National Security

As outlandish as it may seem, in some countries artists may find themselves accused of violating national security laws merely for making art. See “Sentencing of Chinese Political Cartoonist Jiang Yefei and Activist Dong Guangping is the Unjust Result of an Unjust Process,” July 27, 2018, and “Nasrin Sotoudeh,” PEN America. In countries with hard-line governments, artists who are seen as promoting agendas that pose a threat to a ruling regime or endorsing the cultural mores of a country deemed an enemy of the state may be prosecuted under draconian national security laws. See “Aras Amiri Tried to Educate British People About Iranian Culture. Now She’s Serving a 10-Year Prison Sentence in Iran,” Center for Human Rights in Iran, November 16, 2019. In the latter case, artists may be accused of using foreign cultures to dismantle the state, posing a danger to society. Convictions under national security laws can carry some of the most hefty prison terms of any on this list.

In Hong Kong, after months of historic pro-democracy protests against China’s encroaching influence on the semi-autonomous island, Chinese officials rushed a national security law through the legislature. The law, which criminalizes acts of protest against Beijing and severely weakens guarantees of freedom of expression within the city on vaguely defined “national security” grounds, has ignited widespread fears that Hong Kongers’ civic freedoms are being erased. “Hong Kong’s national security law: 10 things you need to know,” Amnesty International, July 12, 2020. In the weeks after it was passed, prominent artists, writers, publishers, and activists have been arrested or forced into exile, See “Hong Kong Activist Arrested Hours After PEN America Event,” PEN America, September 24, 2020 and “Serious concerns over arrest of media publisher and pro-democracy activist Jimmy Lai,” PEN International, August 11, 2020, e.g. as their pro-democracy work is now considered a threat to China’s national security.

Criminal Codes

Performance artists and musicians, whose work often incorporates or occupies public spaces, can be especially vulnerable to charges of hooliganism Shaheed 8. or vandalism. Baha’ Ebdeir, “Taeyong Jeong,” Artists at Risk Connection, April 2019, e.g. Obscenity “Ahmed Naji,” PEN America, e.g. and blasphemy “Joint Statement on the Conviction and Death Sentence of Nigerian Singer Yahaya Sharif Aminu,” Artists at Risk Connection,” August 14, 2020, e.g. laws are also frequently used to criminalize artists. Similarly, when a government truly wants to silence artists or activists, a common tactic is to accuse them of economic crimes, such as spurious tax- or embezzlement-related charges. See “Ai Weiwei” or “Kirill Serebrennikov,” PEN America. To guard against such treatment, it is crucial for artists to maintain financial security and legitimacy. When trouble arises, an error in your finances might be the reason a government that dislikes you is able to put you behind bars. For more on financial security, see “Preparing for Risk.”

***

Ultimately, laws are ever-changing, as are those in power, so it’s impossible to give comprehensive recommendations that apply across the globe. Instead, we suggest staying up to date on your country’s attitudes toward freedom of expression. To keep track of laws that might pose a threat to your artistic practice, you should familiarize yourself with organizations that maintain detailed, annual country reports, such as Freedom House, Freemuse, and Human Rights Watch.

Whether or not you actively criticize the government or call for social change in a hostile environment, there is a wide range of scenarios that could endanger your well-being. To prepare for them, it is essential to understand and assess the types of threats that you might encounter. Hopefully those threats never materialize, but knowing what they look like is crucial to effectively and safely navigating them if they do.

Section II: Preparing for Risk

Whether or not you think you will be put at risk because of your practice, there are other important preemptive steps you can take, including minimizing your visibility as a target, setting up a plan and support network, and ensuring your financial security.

Avoid Making Yourself a Target

One of the simplest ways to minimize risk is to prevent yourself from becoming a target. “Don’t Let Yourself Get Involved in a Cyber Attack: Tips & Tricks,” National Home Security Alliance. Following certain steps and protocols can lessen the likelihood that your artistic practice reaches the attention of hostile forces. Steps as simple as making your social media profiles private, curating the content that you show in public, and restricting your audience can give you some control over who engages with your art, helping you to avoid the wrong people.

Unfortunately, reducing your visibility or going dark online could have profoundly debilitating effects on your career and income. This dilemma can be stark and painful: Keep working at the same level of scrutiny and you might face serious risk; lower your profile and your practice might suffer. Self-censorship inhibits many artists around the world. Instead of self-censoring for fear of retaliation, consider entering a “dormancy” period, staying below the radar for a limited amount of time. Such decisions require careful calculations, weighing the shortest possible time you might need to go quiet against the longest possible time you can stay safe without compromising your work.

In the end, most artists simply follow their instincts. If something gives you pause, don’t ignore that feeling. Ask yourself: Why does this make me uneasy? What about this artistic endeavor might be endangering my work or safety? If your gut is telling you that you might be putting yourself in a sticky situation, your gut is probably right. That said, even in situations that don’t seem excessively risky, preparations never hurt.

If you reach the conclusion that reducing the visibility of your work alone cannot avoid making you a target, you can instead prepare for potential repercussions, deciding in advance and in some detail on the most effective ways to navigate and, ultimately, counter them.

Setting Up a Support Network

The experience of persecution can be not just risky but also isolating. One of the most important steps you can take to protect your mental and physical well-being is to establish a wide, diverse, and supportive community of peers.

If you are about to release or promote work that you believe could attract dangerous attention, you should notify this support network to make sure that it’s ready and able to respond. Support networks can be deployed to counter hateful speech online, “Finding Supportive Cyber Communities,” Online Harassment Field Manual, PEN America. to provide safe shelter, or to raise awareness about your case in your stead if you have been detained or kidnapped.

Developing a support network is a process that is completely within your control, and it can help you feel empowered and encouraged. Identifying and building a community of friends, colleagues, and like-minded professionals in your field who will stand in solidarity with you—people you can trust and reliably turn to for assistance—can give you peace of mind during calmer times and defend you if trouble arises. “A Safety Manual for Political Cartoonists in Trouble,” CRNI, 2016, p. 6.

Beyond your immediate network, having a number of international organizations, including human rights, free expression, and artistic-freedom groups, available to turn to as part of your network is of critical importance. You do not necessarily need strong personal relationships with these organizations, although, whenever possible we encourage fostering such relationships; merely having an array of organizations that can advocate for you, as well as direct contact information for each of them, must be a part of an artist’s toolbox. Ibid.

It is crucial to be able to easily communicate with your network once risk erupts. Many artists send simple messages notifying their contacts when they are attacked, arrested, or imprisoned. You should be able to easily and quickly reach them through a variety of communication channels, which should be as secure as possible. We recommend making sure that everyone in your network has encrypted messaging or email platforms (see the “Digital Safety” section for more specific recommendations). In urgent situations, such channels can include private messages on social media and email listservs that allow you to blast large numbers of people at once. You should also be able to quickly blast messages to the international organizations, or facilitate a way for your direct network of peers to do so, making the organizations immediately aware of your situation so they can dispatch aid.

Making a Plan

With your support network, you should develop an action plan “Protection of Editorial Cartoonists,” Cartooning for Peace, 2019, p. 39, e.g. to quickly and collectively respond to threats. Because no one knows more about your case than you, you must be prepared to be the locus and leader of this plan. At the same time, you must implement processes for your network to take action on your behalf in the event that you are detained or otherwise unavailable to take action.

Your plan might change over time as your adversaries and their tactics change. You must be flexible and make sure that everyone in your network knows about these changes as they happen.

When developing a plan, the first step is usually engaging your most intimate network: your family and attorney. CRNI 7. Sit down with them and evaluate your strengths and weaknesses and the resources at your disposal. Next you should evaluate your wider network, including peers, colleagues, like-minded professionals, and international organizations, to identify their assets and strengths. Each one can likely contribute something unique to your plan of action—a journalist friend might be able to cover your story, a peer might have studio space where you can store your artwork for safekeeping, an organization might have access to a safe house or urgent funds.

Most importantly, you should plan ahead. If you are about to, for example, share something online, release a song, or unveil a work of art that you know might put you at risk, contact your support network beforehand and make action plans to prepare for a number of outcomes.

Such plans should address:

- Your safety and security:

- If you are put at risk, what steps can your network take to keep you safe?

- Can your network provide safe housing or temporary shelter?

- Your family’s safety and security:

- If you are put at risk, what steps can your network take to keep your family safe?

- Will your family be vocal about your case, and if so, how can they prepare for risk themselves?

- Can your network provide a temporary or long-term safe haven and shelter to your family?

- Your legal security and plan:

- If you are placed at risk of legal threats, such as arrest or imprisonment, do you have legal counsel?

- Can your support network mobilize legal support, including fundraising?

- Can your support network be mobilized to help you post bail?

- If you are taken to jail, does your network have a plan for how to reach you, share information about your case, and ensure your physical safety?

Preparing with Your Lawyer

When making a plan, it is crucial to consult an attorney or legal expert. While not everyone has access to legal representation, a number of organizations offer pro bono services, and countless online sources can educate you on your rights in your country and under international law. A lawyer will be able to identify areas of the law that can be invoked to protect you from those who threaten you. If you are arrested, it is vital to have an attorney at hand to help you navigate the logistical realities of posting bail, ensuring your due process rights, and being represented throughout the criminal process. Integrating an attorney’s expertise into your action plan will help ensure that you know your rights, know your country’s laws, and know the legal recourse available to you. You should also discuss immigration possibilities with your lawyer, in case you need to obtain proper documentation and flee the country.

Financial Security

As noted previously, when a government wants to silence artists or dissidents, the first place it will often turn to is their finances. Martin Luther King Jr. was targeted for tax-related crimes, Kelly Phillips Erb, “Why Justice Matters: The Income Tax Trial Of Martin Luther King, Jr.,” Forbes, January 15, 2018. which eventually proved spurious, as a pretext for imprisoning him on grounds unrelated to his civil rights actions. More recently, Kirill Serebrennikov, a Russian theater director, was charged with embezzling money from his theater company. Sadovskaya, Artists at Risk Connection. He was ultimately convicted of this obviously false charge, and though his sentence—a fine, probation, and a three-year ban on leading any state-backed cultural institution—was lighter than expected, it was seen by some as a warning meant to chill others who contemplated cultural expression that could anger the powers that be. When the chips are down, financial crimes are some of the easiest for hostile governments to pursue.

Ai Weiwei, one of the world’s most prominent political artists, was arrested by Chinese authorities in April 2011 and held for 81 days without charges. He was and remains an outspoken critic of the Communist Party of China and has conducted extensive research into government corruption and human rights violations. Despite a lack of charges, officials eventually hinted at “economic crimes,” a tactic often used by governments to silence critics by going after their finances—claiming infractions like tax evasion and fraud—instead of directly targeting their human rights activities. “Ai Weiwei,” PEN America.

ARC is not able to give financial advice, but we recommend taking action to ensure that, if a government wants to silence you, it cannot go after your finances.

Steps we recommend include:

- speaking to a financial adviser

- familiarizing yourself with your country’s tax laws and making sure you are paying all applicable taxes

- keeping accurate, detailed, and consistent records of all financial transactions and expenses, especially those related to your artistic practice.

Escape Plan

While an escape plan should typically be activated only as a last resort, you and your network should prepare for any eventuality. If truly severe threats occur, you may be forced to go into hiding or flee your city, region, or country altogether, even if that means giving up some of your power as a voice of dissent and driver of change. When such drastic measures are required, having a plan already in place is crucial.

In drafting an escape plan with your network, be sure to address the following questions:

- If staying in your country is safe, can someone in your network offer you safe housing in your city, in your region, or elsewhere in the country? How can you get from your location to the safe house swiftly and without being identified? What do you need from your network to make this plan a reality, and how can you activate it while making sure to, in turn, protect your network?

- If staying in the country is not safe, can anyone in your network offer you safe housing elsewhere in your region of the world?

- If you need to flee the country, do you have all the proper documentation? Any escape plan should factor in which countries you can travel to without a visa and which ones require visas.

- Speak to your attorney about acquiring necessary documentation.

- If you anticipate needing to flee the country and wish to go somewhere that requires a visa for entry, you should arrange for this visa beforehand, as the process of obtaining one can take a while.

- If you intend to relocate for a long time but not permanently, make sure that your documents will not expire while you are abroad.

- If you have to flee to another country, which ones are safest? Do any countries have relationships with your country’s government that would allow them to extradite you?

- If you have to flee to another country, can you go someplace where you speak the language?

- Can an organization or host institution provide you with safe housing in your region or another country?

- How will you sustain yourself once you are in hiding? Can your network support you, or will you need to withdraw savings or apply for urgent funding?

- How long will your escape last for? Do you plan on returning, or relocating permanently? If the latter, do you need to consider seeking political asylum?

- Does your family also need to escape? If so, how can they do so safely? All the aforementioned questions will necessarily apply to family members looking to escape as well.

To ensure that your escape can be executed swiftly and safely, each of these questions should be discussed at length, thoroughly, and well in advance of any anticipated risk with your family, support network, and attorney.

You Can Never Be Too Prepared

There are countless further steps that artists should take to prepare for risk. But in short, you can never be too prepared. If you fear there’s a chance—even a remote one—that you might be put at risk, you should take all steps necessary to prepare for all possibilities, from the lowest to the highest threat. This way, no matter what happens, you will have a foundation to help you react. Support networks and action plans are two of the fundamental ways to lay this foundation and feel that you are ready and not alone when trouble arises. If you are ever looking for advice on how to prepare and/or want to make connections to help lay the groundwork for a contingency plan, you can contact ARC through our website.

Section III: Digital Safety

New digital technologies are transforming the art world. Social media and music streaming channels are becoming the platforms on which artists publicly display and promote their work. But these platforms have also generated an array of threats to artists’ rights and freedom of expression. Such threats can come from a variety of sources—state governments seeking to surveil and censor online spaces, abusive trolls seeking to intimidate artists into silence and self-censorship, hackers seeking to undermine or breach artists’ content and data, and more. One of the most effective things you can do to mitigate and prevent risk is to bolster your cybersecurity practices.

A large and growing number of ARC’s cases concern digital safety, and many requests for urgent assistance deal with some sort of online harassment. In 2017, PEN America conducted a survey of over 230 journalists and writers in the United States and found that 67 percent of respondents had reacted severely to being targeted by online harassment—refraining from publishing their work, permanently deleting their social media accounts, fearing for their safety or the safety of their loved ones. In authoritarian countries, many artists and writers are frequently surveilled or attacked online by state agents and have had speech or online content, sometimes from their personal social media accounts, used against them in courts of law. Online harassment and security breaches can come in so many shapes and sizes, and via so many different mediums and platforms, that merely contemplating how to prepare for them can feel overwhelming. But being proactive is infinitely more effective than being reactive. The following section will provide tips, guidelines, and best practices for protecting yourself and your personal information from hacking, doxing, impersonation, and other forms of online harassment.

Because ARC does not specialize in digital security, and because there are far more comprehensive resources that offer specific recommendations, the steps outlined in this section are intentionally broad. Cybersecurity is such a dynamic and nuanced topic that platforms that are safe for an artist in one country or at one time may be dangerous for an artist in another country or at another time. For specific and continually updated recommendations and information, we suggest looking at the “Further Resources” section below.

Passwords

Establishing secure passwords is a simple yet crucial first step for protecting yourself online.

- Use a password manager to create and store passwords. To access your password manager, you will need to create a long and unique password. If you feel you are being targeted by a government or you feel you are at risk of being detained then you should regularly log out of your password manager as you would your other accounts.

- A strong password, like those generated by a password manager, ideally has at least 16 characters and contains a mix of upper- and lowercase letters, symbols, and numbers.

- Avoid using personal data, such as your date of birth or address, in your passwords. This information can easily be found on social media and online databases.

- Do not reuse passwords—create a unique password for each individual account.

- If you feel that you are being targeted by a government or that you are at risk of being detained, you should regularly log out of your password manager as you would your other accounts.

- Using security questions is another important way to protect yourself from breaches to your accounts, but it is important to pick difficult questions and answers that aren’t searchable on Google. The Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF) recommends using a fictional or randomly generated answer in response to these questions.

Don’t forget all the different accounts out there! Email, social media, banking, household expenses like electric and heating, credit cards, health insurance, television and movie subscriptions, and memberships are just some of the online accounts you might have. Keep in mind: Even if the account itself is not that important to you, if it is breached, your private data (home address, credit card, etc.) could be exposed. If you have accounts that you no longer use, you should take steps to delete them, but remember to erase your personal information from the account first.

Multifactor Authentication

Turn on multifactor authentication (also known as two-step verification) whenever possible. This extra layer of security will help protect your accounts if your password has been compromised. There are three types of multifactor authentication:

- Provide your cell phone number and get text messages with access codes

- Download and install an authenticator app, which randomly generates secure codes

- Get a physical security key.

Any form of multifactor authentication is better than none. But if your threat comes from a government or a group with sophisticated tech capacity, we recommend using authenticator apps and physical security keys. These methods are more secure than text-message-based authentication, offering stronger protection against a phenomenon called SIM hijacking (see more information below).

Establishing a secure email account is crucial for protecting yourself from privacy breaches, unsolicited or threatening messages, and surveillance by state- or non-state agents.

Account Management and Security

- Choose your email address carefully. While many or even most people use email addresses that contain identifying information for business and commercial purposes, we strongly advise that artists aim for an address that does not reveal identifying information, like your name, ethnicity, age, religion, gender, sexual orientation, location, place of employment, or interests.

- Use a password manager and turn on multifactor authentication.

- Keep your personal and professional emails separate. If you use a specific email address for professional purposes, use a different one to communicate with friends and loved ones. (Ideally, you would also have a third email for things like e-commerce, services, newsletters, etc.)

- If you need to send messages containing sensitive information, whether personal or professional, consider sending them instead via Signal, an end-to-end encrypted messaging app.

Handling Email Harassment

- Beware of spam and phishing. Think carefully before opening unexpected or unsolicited emails. Try to verify the identity of the sender via another channel, such as a website. Use the Preview option to view attached documents within the email instead of clicking on them or downloading them to your device.

- Ask your workplace, university, or volunteer affiliations not to publish your contact info in their online directories or on their “about” pages, to protect your email address from circulating and attracting unsolicited inquiries or spam.