Artist Profile

Wanuri Kahiu

Kenya

When asked about the motivation behind her controversial and critically-acclaimed film Rafiki, Kenyan director Wanuri Kahiu offers this simple response: “More than anything, I just wanted to tell a love story. Truly cinematic love stories from Africa are few and far between. I wanted to be able to add our love to cinematic history.”

It was not an addition that went unnoticed. Between dozens of international awards nominations and a years-long domestic court case, Rafiki has been met with both praise and suppression for its unapologetically joyful portrait of young love against all odds.

Kahiu is a director, producer, and author from Nairobi, Kenya who has been pursuing her passion for storytelling through film since she was 16 years old. Her debut feature film, From A Whisper, received several awards at the 2009 Africa Movie Academy Awards for its fictionalized depiction of the 1988 terrorist attack on the United States embassy in Nairobi. Her other early works include Pumzi, an Afrofuturist story of a young botanist living in post-World War III Africa, and For Our Land, a documentary about the life of Nobel Peace Prize laureate Wangari Maathai.

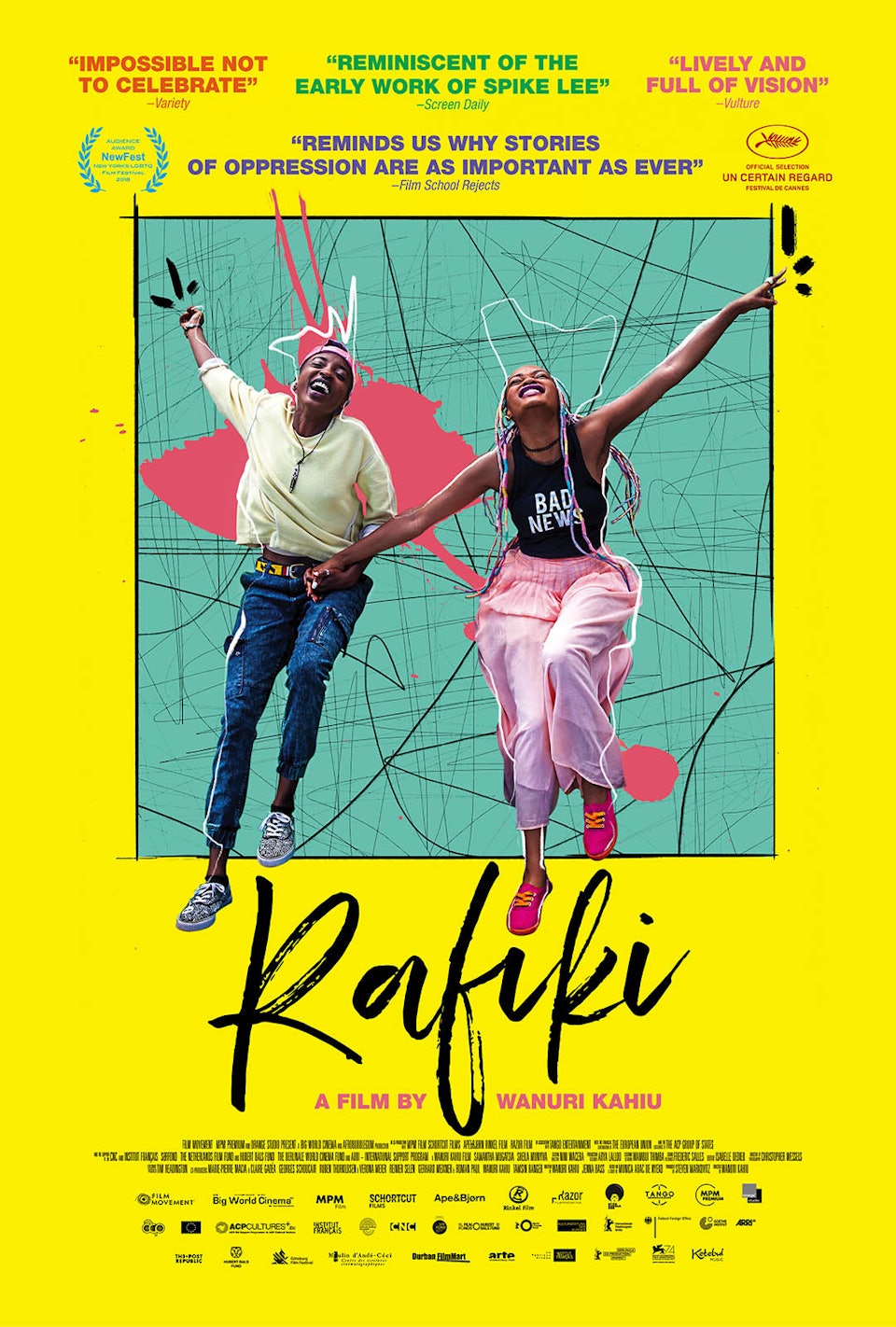

But it is Rafiki, Kahiu’s film adaptation of the Ugandan short story “Jambula Tree” by Monica Arac de Nyeko, that has gained the most attention in both domestic and international spheres. A candid and heartwarming story of two young Kenyan women in love, Rafiki was quick to receive both domestic backlash and international accolades for its tender, nuanced depiction of young queer romance against a conservative backdrop. In April 2018, the month preceding the film’s release, it made history as the first Kenyan film to be selected for screening at the Cannes film festival. However, that very same week, it was reviewed by the Kenyan Film Classification Board and banned in the country for “promoting lesbianism” and deemed “contrary to the law and dominant values of the Kenyans.” Due to the legacy of colonial-era law, homosexuality is illegal in Kenya and can be met with up to fourteen years in prison.

“They felt it was too hopeful,” Kahiu explained in an interview with The Guardian following the decision. “They said that if I changed the end to show [the main character Kena] looking remorseful, they would give me an 18 rating.”

But Kahiu refused. Hope, after all, is the backbone of her work; she aims to shift depictions and perceptions of Africa away from what she cites as the all-too-dominant themes of war, poverty, and disease.

“I think there are more instances of joy than remorse in Africa,” she says. “If we don’t see more images of ourselves as hopeful, joyful people, we won’t work towards it.”

It was with this image in mind that she created AFROBUBBLEGUM, a collective of African artists and creatives working toward a “new vision of Africa” that centers on joy, hope, and love. By emphasizing an image of African life as one of vibrant happiness, AFROBUBBLEGUM’s mission aims to reject the idea that all media about Africa and its people must be serious and issue-centric. In a 2017 TED Talk, Kahiu explained this goal by offering up her own version of the Bechdel test: to meet the AFROBUBBLEGUM standards, a film must include “at least two healthy Africans who are financially stable, having fun, and enjoying life.”

When watching Rafiki, it becomes apparent that the film was born out of this movement. Its vibrant, hopeful depiction of love and intimacy stands in stark contrast to the monolithic images of African life that Kahiu references. Though it acknowledges the danger faced by the two main characters at the hands of homophobic post-colonial law and culture, these moments are tempered by the radical joy that courses through the story––the same joy that, contrary to the wishes of the Film Classification Board, Kahiu was adamant about emphasizing in the film’s final scene.

Despite being met with an overwhelmingly positive response from the international film community, Rafiki and its creators received their share of negative attention as well. Following the film’s international release, Kahiu was subjected to harassment, hateful messages, and threats on social media and in person, from strangers as well as friends, family, and community members.

Kahiu, however, refused to give into censorship or self-censorship. After receiving notice of the ban on Rafiki, she sued the Kenyan Film Classification Board, claiming that the decision violated her constitutional right to freedom of expression. This was the first time that an artistic freedom case had been brought before the country’s constitutional court.

In response to her lawsuit, Kenya’s High Court granted a conservatory order and temporarily lifted the ban on Rafiki for seven days, just enough of a run to allow the film to qualify for the Oscars. Its domestic premiere in Nairobi was on September 28th, and sold out theaters across the city.

Following the weeklong lift, however, the movie was forbidden once again and court arguments continued. Kahiu enlisted the help of Article 19 East Africa, who advocated alongside her that the Kenyan Constitution ensured citizens’ right to express all ideas, even subversive or non-mainstreamed ones, in contribution to public debate on cultural issues. "The case has become larger than the film, because the case is not about Rafiki," Kahiu said to NPR. "The case is about freedom of expression."

Finally, on April 29, 2020, two years after the initial decision, the High Court ruled in favor of the Film Classification Board, deeming their actions constitutional and upholding the ban. On Twitter, Kahiu called the decision “a sad blow for freedom of expression and freedom of speech in Kenya.” Nevertheless, Kahiu intends to continue the legal fight.

Despite the domestic controversy surrounding Rafiki, it has received countless international accolades, including 11 wins and 13 nominations in festivals across the globe. This flurry of attention and praise has all eyes on Kahiu, whose slew of upcoming projects includes a television adaptation of the Octavia Butler novel Wild Seed, in conjunction with Nnedi Okorafor and Viola Davis.

With regards to the film’s ongoing ban, Kahiu shows no sign of resignation. “We will continue to fight against laws that have no place in our Kenyan society,” she said of the disheartening decision. “We believe in our constitution and we are glad we have the right to defend it. We will appeal! A luta continua!”

By Cobie-Ray Johnson, October 2020. Cobie-Ray Johnson is a senior at Barnard College studying Economics and Human Rights.