Artist Profile

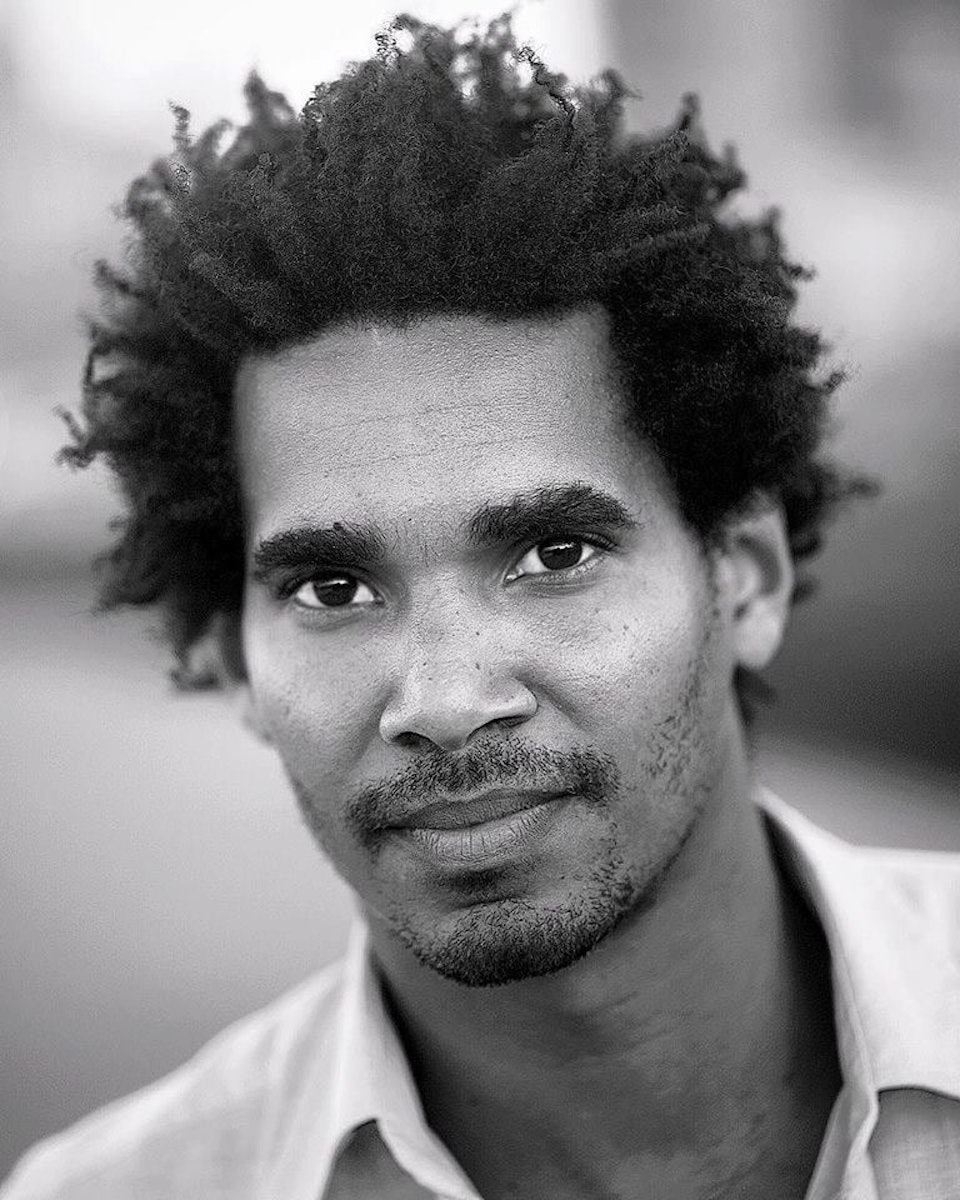

Luis Manuel Otero Alcántara

Cuba

Status: Detained

UPDATE: May 30, 2022 marked the first day of Luis Manuel Otero Alcántara's trial on charges that include defamation of public institutions and national symbols, contempt, and public disorder. Representatives from the Havana embassies of several countries were denied entry to the court proceedings. In a statement sent from the Maximum-Security Prison of Guanajay, Cuba on May 17, Otero Alcántara asked the public "to support free art, and to support my art, wherever I am. Do not leave me alone. Let us not leave the course of Cuba in the hands of a dictator or the course of destiny."

UPDATE: On April 7, 2022, Cuban prosecutors recommended that a sentence of seven years be imposed on Luis Manuel Otero Alcántara. The unsubstantiated and outrageous charges against Otero Alcántara include “insults to symbols of the homeland,” “contempt,” and “public disorder." ARC calls on the Cuban government to drop these charges and release Otero Alcántara immediately.

UPDATE: On January 24, 2022, Luis Manuel Otero Alcántara, who remains incarcerated at a high-security prison in Havana, began another hunger strike. He is in poor health due to his lengthy detention and previous hunger strikes, as well as a bout of COVID-19. PEN America is deeply concerned about his current situation and urges the Cuban government to release him immediately.

UPDATE: On September 27, 2021, Luis Manuel Otero Alcántara began a hunger strike at a high-security prison of Guanjay, where he has been detained since mid-July, in in protest of his imprisonment and continued repression against artists in the country. Read PEN America's statement here.

UPDATE: On September 6, Luis Manuel Otero Alcántara was charged with the crimes of public disorder, contempt and instigation to commit a crime.

UPDATE: On July 11, 2021, Luis Manuel Otero Alcántara was detained in the maximum-security prison of Gaunajay.

UPDATE: On May 31, 2021, Luis Manuel Otero Alcántara was released after nearly a month of detention in Hospital Calixto Garcia in Havana, Cuba. Read PEN America's statement here.

UPDATE: On December 3, 2020, after being hospitalized for a hunger strike in protest of the government's treatment of the San Isidro Movement, Luis Manuel Otero Alcántara was released and subsequently detained and placed under de facto house arrest.

In an Instagram video from February 5, Cuban artist Luis Manuel Otero Alcántara slowly twirls a construction helmet. On it is written: “Los niños nacieron para ser felices no para morir en derrumbes,” which translates to, “Kids are born to be happy, not to die in landslides.” The helmet was created in response to a construction accident that killed three schoolgirls in Old Havana, an incident which Otero Alcántara says is the “total responsibility” of the Cuban government. To mourn these three girls and to draw public attention to the role of the Cuban government in their deaths, Otero Alcántara walked around Havana wearing his construction helmet for nine days, calling it a “novena” for the girls’ lives. The result was a distinctly Otero Alcántara-esque performance piece: part spiritual invocation, part public spectacle, and part feat of bodily endurance.

Otero Alcántara has been performing his artworks in public spaces for years. An artist of astounding breadth, his works feel both irreverent and politically-charged, while still maintaining the direct-eye-contact-warmth that good, personal performance art has. (This intimacy is particularly noticeable in his social media presence, where the artist narrates his multi-day performances to an enthusiastic following.) Otero Alcántara did not develop his practice as part of the “privileged” artist class in Cuba: before making art full-time, he was a professional endurance racing athlete, but found that he “couldn’t speak up or express [himself]” in the ways that he wanted to.

Otero Alcántara’s family lived in the Cerro neighborhood in Havana, which is one of the poorest areas in Havana. Growing up, he says that art was largely unknown to him. That all changed when he was seventeen and he discovered through friends what he describes as the “infinite world of art.” At first, Otero Alcántara was more interested in sculpture, feeling that it was a “more realistic copy of reality.” Eventually, that quest for tangible impact in his art — the “search for work that contributed to the reality in which [he] lived” — led him to performance art, where he could utilize the physical and emotional command learned through athletics to perform marathon sessions of artistic expression. Fittingly, Otero Alcántara describes art as “an extreme exercise,” drawing parallels between the physical and emotional capacities needed for both disciplines.

Protest and dissent––or speaking up in the ways he previously felt he could not––are also central to Otero Alcántara’s practice, and in a country where expression is not always free, he has faced immense challenges as a result. As an autodidact, the “[Cuban] state doesn’t recognize [Otero Alcántara] as an artist because [he] didn’t go to art school,” a status which has proved increasingly fraught in the wake of Cuba’s Decree 349. Signed into law by Cuba’s president in 2018, Decree 349 prohibits artists, musicians, and performers from exhibiting in public or private spaces without government approval. The decree also prohibits art that is “obscene,” “vulgar,” or “harmful to ethical and cultural values,” an imprecise and subjective designation that has led numerous human rights groups to criticize the law. The Decree has granted Cuban authorities broad purview to muzzle dissent and arrest anyone whose speech does not align with their political narrative. ARC and PEN America have documented numerous cases of targeted and ongoing intimidation and detainment of Cuban artists, creating an atmosphere that is fundamentally inimical to artistic expression. It is in the midst of this environment that Otero Alcántara finds himself, as both one of the Decree’s most vocal critics and one of its most frequent targets. Since 2017, he has been arrested an unfathomable 21 times.

It can be confusing to track the Cuban government’s response to each of Otero Alcántara’s performance pieces. The artist has been detained so many different times, for so many different performance pieces, that the government’s responses feel more cyclical than specific: Otero Alcántara enacts a new piece; he is detained by the government, sometimes in jail and sometimes in a pre-trial “preventative prison,” as happened during his most recent detainment; Otero Alcántara is released amid international outcry. In spite of—or, really, because of—the intensity of the government’s crackdowns, Otero Alcántara continues to perform his “art-ivist” pieces, and continues to face detention and persecution as a result. Acting as a sort of lightning-rod for violations of free expression, his works come to embody and therefore raise awareness of Cuba’s ongoing repression of independent artists, writers, thinkers, and activists.

Otero Alcántara’s outspoken opposition to Decree 349 plays out both in his personal artistic practice and within art institutions in Cuba. He is a founding member of the Museum of Dissidence, a Cuban artist collective that has mounted a full-scale protest against Decree 349, including a concert organized to protest the decree. (Otero Alcántara was arrested in his home for his role in organizing the concert. This, only weeks after a previous arrest for his role in a demonstration on the steps of Cuba’s capital building: he filmed a fellow artist and Museum of Dissidence co-founder, Yanelyz Nuñez, covered in human feces to protest the passage of Decree 349.) Otero Alcántara has cultivated a community of fellow art-ivists, as well: he is the general coordinator of the San Isidro Collective, a collective aiming to promote freedom of expression, and helped organize the #00Bienal de la Habana, the first non-state-sanctioned art biennial in Cuba.

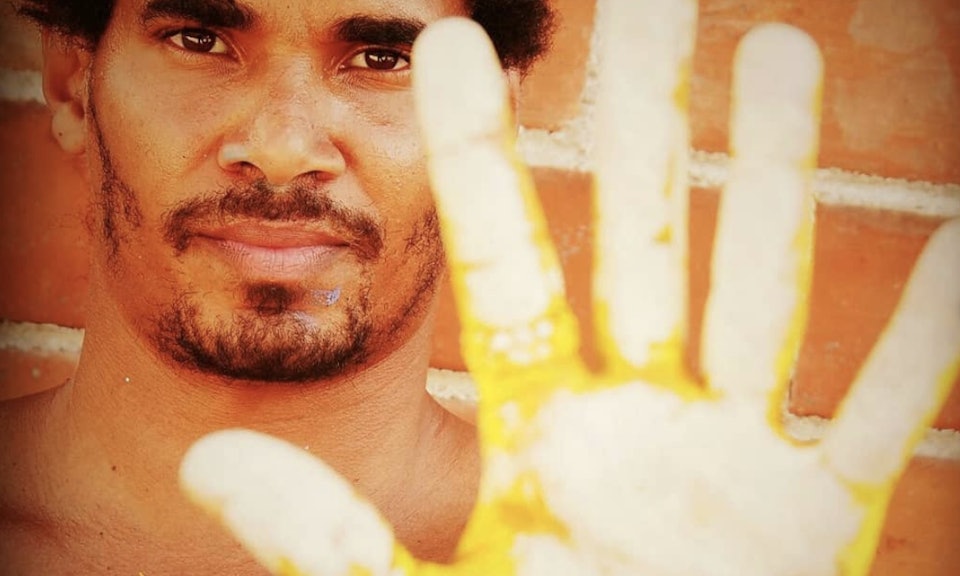

His performances themselves defy easy categorization, ranging from the intentionally absurd to the poignantly political. In one piece, Super Pijo, Otero referenced a Joseph Beuys performance piece, painting his face white and carrying around a rabbit. On the more political end of the spectrum, Otero Alcántara performed a piece called Drapeau in which he wore a Cuban flag draped over his shoulders for thirty days straight, a response to a Cuban law limiting the ways that the national flag could be displayed. Whether he’s engaging with the very political or the very personal, Otero Alcántara “like[s] going to the extreme to make people think.” Like Marina Abramovic or Joseph Beuys, his artworks double as feats of physical endurance. By capturing the attention of his viewers, and of the Cuban government, Otero Alcántara insists that they consider why he would put himself through the ordeals of his art: why he would wear a flag around his body for thirty days, or why he would smear his body in human feces. In doing so, he raises questions about the nature of artistic expression, and about the importance of public discourse under a totalitarian regime. The Cuban government’s response — to censor his performances, deeming them decidedly not-art — has the unintended consequence of drawing attention to the power of his subversive art form.

Otero Alcántara’s body is his primary medium for artistic expression. As evinced by his hard-hat novena, the streets of Havana—and, by extension, his online records of his street activities—are his canvas. In a country where artistic expression has been repeatedly attacked and undermined, Otero Alcántara paints the streets with his protests and performances, rendering the Cuban government’s responses to his art as absurd as the performances themselves. In the process, he continues to engage with a long, important history of art under totalitarianism: its bravery, its punishments, and its rewards.

UPDATE: On June 11, Luis Manuel Otero Alcántara was arrested alongside rapper Maykel Osorbo and showed signs of beating. He was released the following day.

By Annie Kiyonaga, April 2020. Annie is a recent graduate from University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, where she studied art history and literature. She currently lives in New York, where she’s working for an education non-profit.