Bullets and a Blank Canvas: Marking two years since Myanmar's coup

Myanmar

It happened early in the morning, when the country was just waking up. On a wide, sunlit boulevard in Naypyidaw—Myanmar’s political capital—a military convoy moved slowly towards the Presidential Palace. It was February 1, 2021 and a young woman livestreaming her workout from a street corner caught it all on camera. As she stepped in time to an upbeat pop song, the black vehicles moved in unison behind her, on their way to arrest the democratically-elected State Counsellor Aung San Suu Kyi and President Win Myint.

One year into the COVID-19 pandemic, that video went viral. Even for those who knew little about Myanmar’s history, it seemed to capture a spirit of the times; many could relate to the feeling that they, too, had been dancing, distracted, as a catastrophe unfolded just out of view.

History was being made in real-time: Myanmar’s five-year period of civil government, democracy, and relative media and artistic freedom was coming to an end in the blink of an eye.

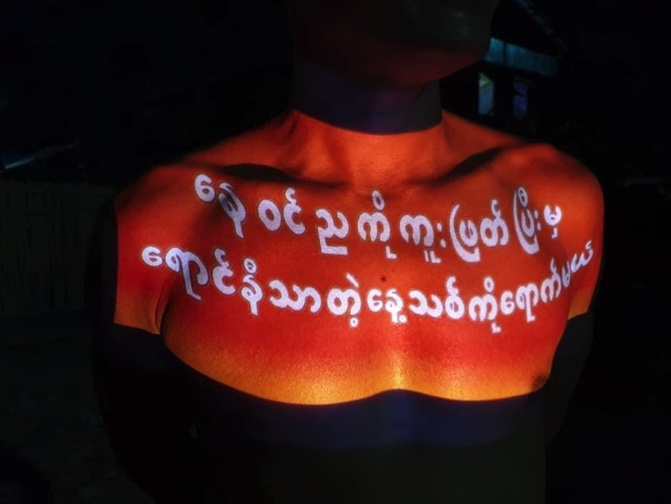

Now, two years into a new chapter of the military junta’s grip on power, Myanmar is in a protracted state of chaos. At the time of the coup, a mass resistance movement erupted—known as the Spring Revolution—which saw hundreds of thousands of protesters taking to the streets in cities across the country. To date, the Burmese military’s indiscriminate use of violence has claimed the lives of nearly 3,000 protesters. Over 13,500 are in detention, according to the Burmese NGO Assistance Association of Political Prisoners (AAPP). In an article published one year after the coup, ARC’s Manojna Yeluri highlights that Myanmar’s artists were some of the first to be targeted, facing abuse, torture, and murder as a consequence of their creative dissent. As reporting from PEN America details, the immediate effects on all spheres of artistic expression in the country were “devastating.”

Although Aung San Suu Kyi’s National League for Democracy (NLD) government was far from perfect—preserving laws from the days of military rule, continuing to repress the Rohingya Muslim minority, and leaving the Tatmadaw, Myanmar’s armed forces, with significant influence in civil and political life—it represented a major step towards a more pluralistic and free society. After nearly five decades of military government, the election of the Nobel Peace Prize winner and formerly imprisoned pro-democracy activist in 2015 was thought of as a turning point in a decades-long struggle, one that predated the living memory of many.

Myanmar is a youthful country. Over 40% of the population is under the age of 24, meaning that many of those in their twenties came of age after the post-2011 reforms. For the 27-year-old Burmese graphic artist who goes by the name, Bart Was Not Here (born Kyaw Moe Khine), the military coup gave new relevance to his parents’ descriptions of the country. In a 2021 interview with PEN America’s Karin Deutsch Karlekar, Bart references the older generation’s familiarity with the “knock on the door at three o’clock in the morning” that predictably followed any statement that the ruling junta disapproved of.

“We didn't trust the military. From 2015 to 2020, we had some freedom, but we still self-censored.”

— Nge Lay, Burmese multimedia artist, on the power-sharing agreement during the NLD ruling period.

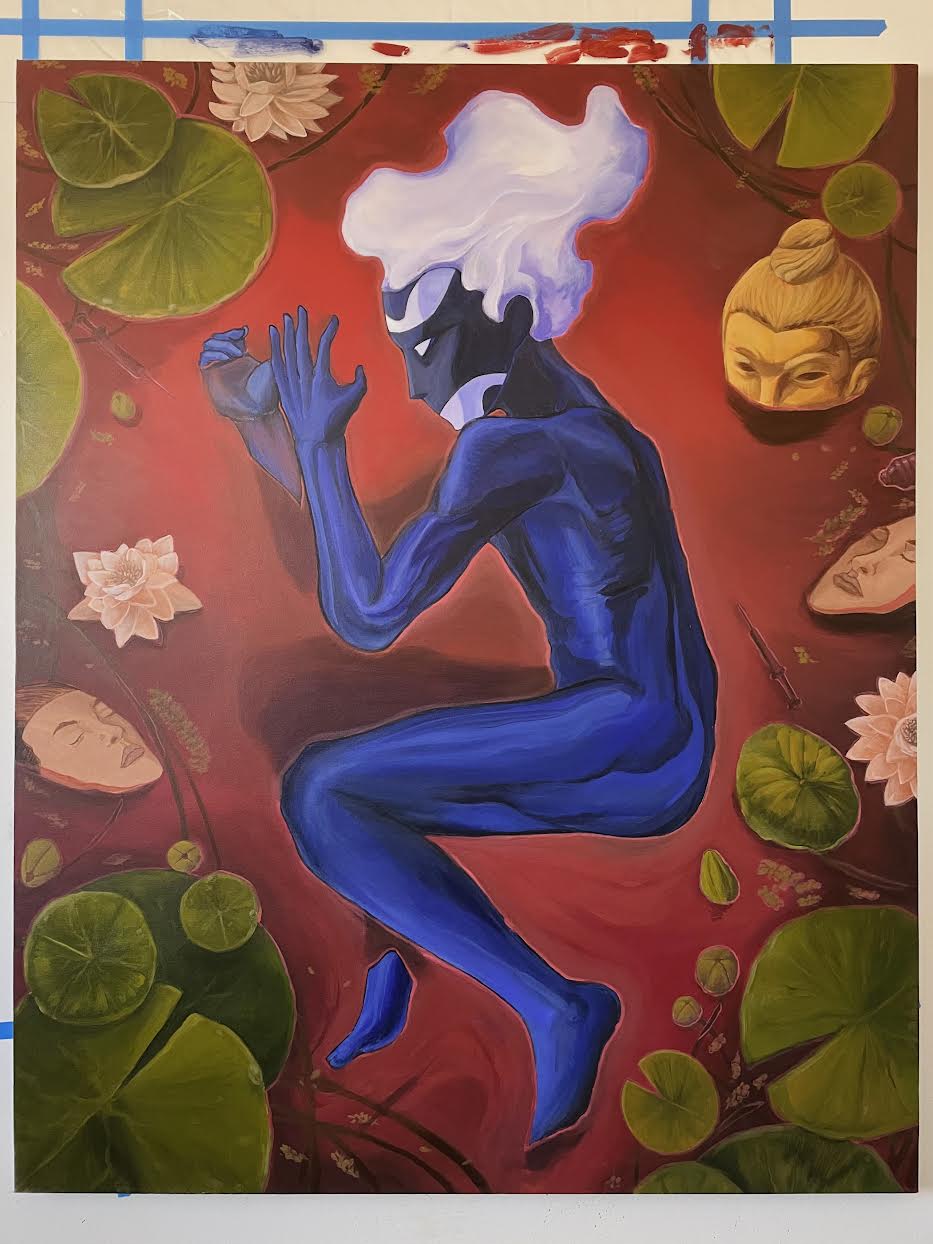

In a January 2023 interview with ARC, multimedia artists and couple Nge Lay and Aung Ko (born in 1980 and 1979, respectively) contend that the creative freedom which existed during the NLD ruling period from 2015 to 2021 was always muted. Lay, whose socio-political work examines Myanmar’s history, memory, and gender roles through superimposing contemporary photography on archival images, states: “We didn’t trust the military. From 2015 to 2020, we had some freedom, but we still self-censored.” There was a sense that the Tatmadaw still possessed major leverage in Burmese society; they drafted the 2008 constitution that opened Myanmar up to the path of democracy. It promised them 25% of all seats in parliament.

The day of the coup, Lay and Ko could not imagine soon leaving their country. The freedom they had as artists—imperfect as it was—was hard-fought. Their lives in Yangon were established, and their 5-year-old daughter was in school. Instead, they joined the tens of thousands of protesters who thronged Yangon’s downtown. When the regime closed off that part of the city, they organized locally in the center of their neighborhood. For five months, they refused to back down, even as the military doubled down on its brutal campaign of repression. Lay recounts the chilling phenomenon of perceived “agitators” being arrested at their homes late at night and bundled into police vehicles, only for an officer to return in the morning and report that they had died. In some cases, the bodies that returned were missing their internal organs. The cause of death that was offered to families: a heart attack.

Lay was aware that she could be a target of the regime; she had worked extensively for an NGO involving an oppressed minority in Myanmar’s south. In her retelling, two considerations led to her decision to seek asylum in France. If she went to prison, she wouldn’t be able to do anything to advance the struggle for democracy in her country. It was better to live in exile than to be rendered powerless at home. The second consideration was that Lay and Ko’s daughter had witnessed an atrocity—the army firing indiscriminately into a crowd—as she played in a playground. At that moment, Lay realized that it was inconceivable to stay. At eight years old, during the short-lived 1988 uprising, she had also watched the army commit a massacre against protesters. Decades later, her daughter was witnessing the same violence unfold. Lay could not bear to watch their child experience the same trauma that she did. In June 2021, the family left to face the challenges of life in exile.

For Bart Was Not Here, the moment that crystallized his decision to leave came when he returned to his art studio after a night spent at a friend’s. For his outwardly political graffiti and illustrations, Bart was facing significant risks. He felt reasonably safe at first, due to the fact that he never used his real name and changed location frequently. But when he approached the door of his studio, it was riddled with bullet holes. The same had been done to his car. He left the country soon after, and after a lengthy collaboration with ARC, now lives in New York.

As other Burmese artists and refugees have testified, the process for gaining asylum abroad was by no means straightforward. Only a minority of people in Myanmar have passports, and of the approximately 19,000 Burmese citizens who managed to leave the country, many find themselves in deeply precarious situations and without formal status in countries like Thailand or India. Over 900,000 people have been internally displaced, according to the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs. The ARC team has found relocating Burmese artists particularly difficult, and Bart, Lay, and Ko are among the few who were able to gain residency and continue their careers in Europe and the US. Now, in a new chapter of their lives, they think about what they left behind.

Bart’s reflections on censorship during the pre-NLD era of military rule are different from Nge Lay’s. For Bart, they are second-hand. For Nge Lay, they are ever-present memories. Bart paints an image of the “old days” when a government censor would make their rounds of artists’ studios, inspecting work for any hint of subversive content, and expecting a generous supply of tea and butter biscuits. While Bart finds some dark humor in this absurd exchange, Lay remembers having to navigate it. She remembers the gap between the official description of a work that was provided to the authorities—attempts to obscure meaning—and the way that a piece actually took form. She remembers the delicateness—and danger—of circumventing what was acceptable.

For this reason maybe, Lay remained somewhat cautious in her practice during the NLD years, while Bart was, in his own words, reckless. He claims: “Everything I had a strong conviction about, I did, no matter what.” As he pushed the envelope of artistic expression further and further, people around him felt vicarious fear. They would grit their teeth and ask if he was worried. His answer, resoundingly, was no.

But on February 1, 2021, that confidence was shaken.

When the military junta led by General Min Aung Hlang took over, the effects on Myanmar’s cultural sector were swift, with the majority of galleries, art schools, arts associations, and other creative institutions forced underground or shut down completely. PEN America’s 2021 report Stolen Freedoms, highlights the actions of younger artists—those who refused to return to the “dark days” of their parents’ generation—who were among the most defiant in producing illustrations, poetry, music, graffiti, and other forms of subversive art. At the time of the report, at least 45 creative artists had been detained, with many more being actively targeted for arrest, while 5 had been brutally killed, and untold more had been subject to abuse and torture. In the last year, the government’s brutal crackdown on dissent has only accelerated.

“Right now, the Myanmar issue is not popular in the world. The western world shifted to Afghanistan and Ukraine, which involve global powers, and large-scale wars. People think of Myanmar just as a civil war, but it’s more than that.”

— Nge Lay, Burmese multimedia artist