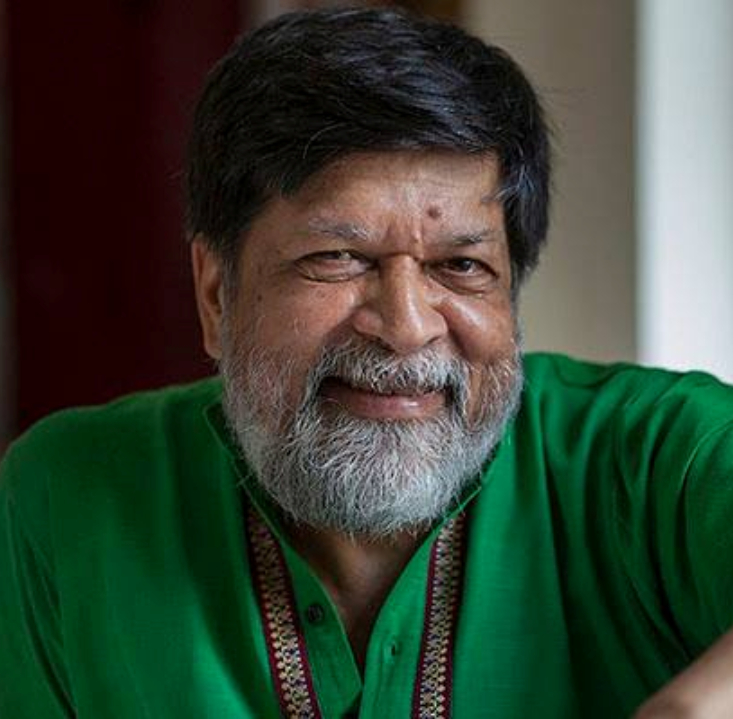

Shahidul Alam

Photographer, Writer

Bangladesh

“It is the person who controls the narrative that determines which story gets told.”– Shahidul Alam

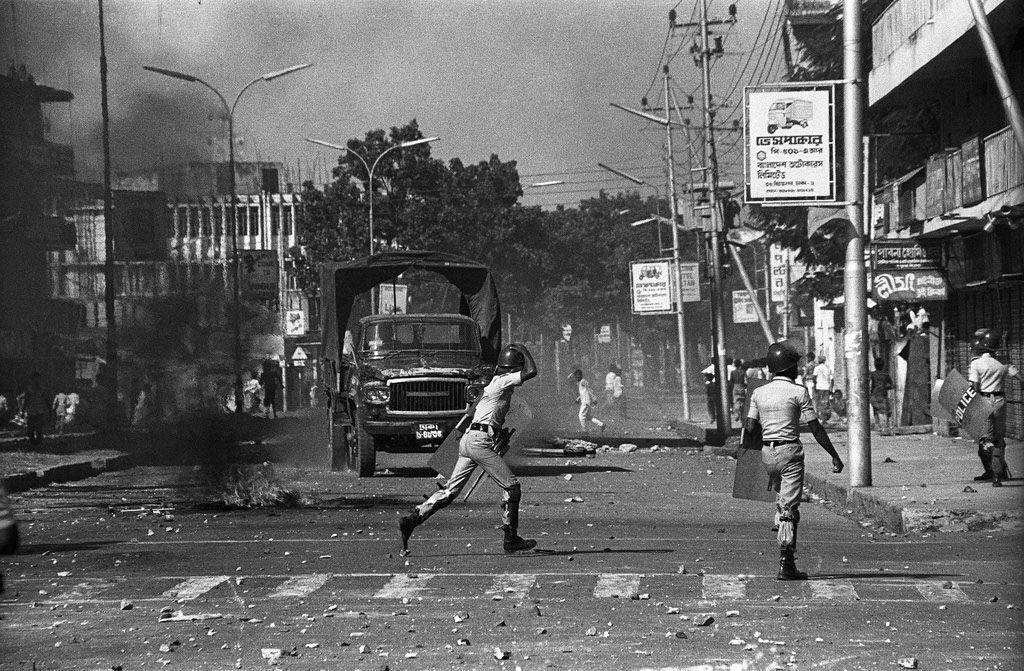

In July 2024, chaos gripped Bangladesh. Peaceful student-led protests against a controversial quota policy in government job appointments spiralled into nationwide riots and brutality against protestors. Dispatches from Dhaka based photojournalist and activist, Shahidul Alam, served to counter the government’s attempts to censor and silence stories of the ongoing violence, highlighting the realities facing those living in the country.

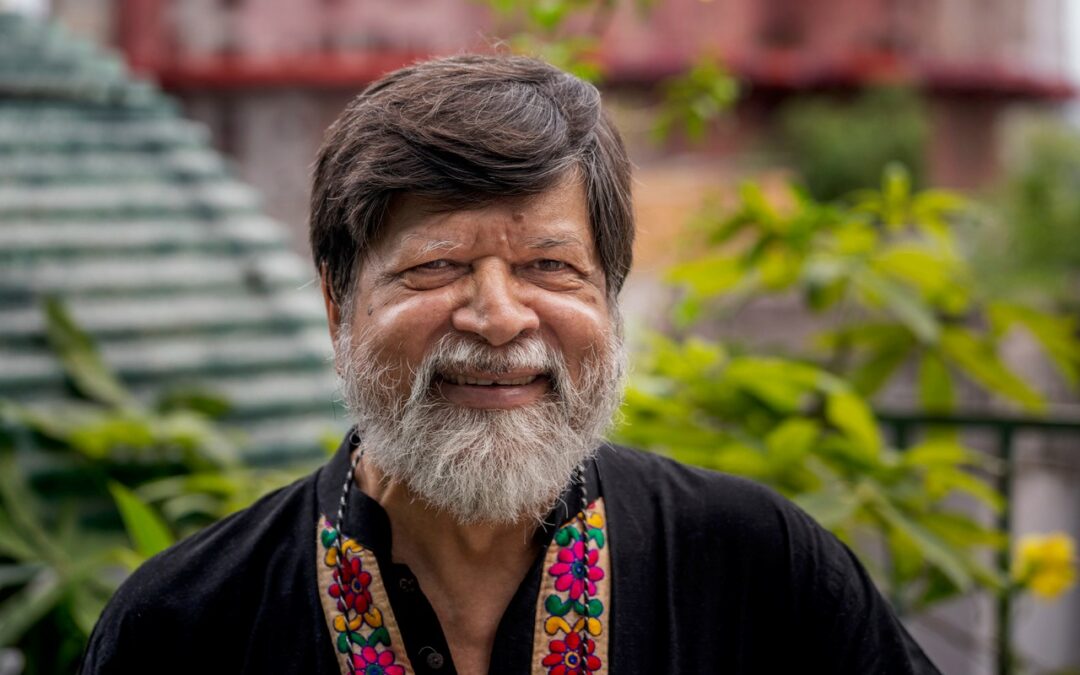

Shahidul Alam released from detention. Courtesy of Saikat Mojumder & Suvra Kanti Das.

For decades now, Alam–a TIME magazine ‘Person of the Year’ for 2018–has devoted his life’s work to telling the stories and revealing the perspectives of marginalized communities in Bangladesh. A renowned photojournalist, educator, arts advocate and activist, Alam is the founder of the Drik Gallery and Majority World agencies–media organizations and platforms that promote the works of photographers from the Global Majority. Alam also founded the Pathshala South Asian Media Institute, now considered one of the best photography schools in the world.

“The fact that I discovered photography and photography gave me so much of joy…was a beauty in itself. It was when I began to see what more it could do besides producing beautiful pictures that I really began to see the strength in it.”

Alam’s career began when he returned to Bangladesh in 1984 after receiving a doctorate in Chemistry from London University. At that time, his home country was in the midst of a democratic struggle to overthrow General Ershad. During the conflict, he took photographs of the protests and eventually published them in a photo essay called “A Struggle for Democracy.”

A few years later, in 1991, he photographed the aftermath of a devastating cyclone in Bangladesh for The New York Times with the intention to challenge the stereotypical image of the global majority world shown through a euro-centric lens. Alam convinced the newspaper to print photographs focused on people rebuilding their lives and supporting one another after the disaster, instead of a voyeuristic account of their suffering.

Alam’s work has garnered international acclaim. His book My Journey as a Witness, published in 2011, was called “the most important book ever written by a photographer” by John Morris, former Picture Editor of LIFE Magazine. The book chronicles Alam’s journey as a photographer and social activist. Alam was TIME magazine ‘Person of the Year’ for 2018, and in 2014, he was awarded the Shilpakala Padak, the highest honor for artists in Bangladesh.

Despite his work garnering global recognition, Alam has found himself brazenly and repeatedly targeted by Bangladeshi authorities. In August 2018, he was arrested while documenting and reporting on the brutal suppression of student protests in Dhaka. Later, Alam was investigated for a live video he posted on Facebook and comments he made in an interview about protests by Bangladeshi students against the Government. He was also charged under Section 57 of the 2009 Information and Communication and Technology Act (ICT) for “making provocative comments” and “giving false information to the media.” The ICT criminalizes various forms of expression on online platforms, carrying up to 14 years in prison in the event of a conviction. Alam was detained for more than 100 days on the above mentioned charges, and was finally released on permanent bail in November 2018. Alam continued to be at the centre of a police investigation, with the High Court suspending the investigation proceedings and dropping all charges only as recently as December 2024.

In June 2024, he returned his honorary doctorate from the University of the Arts London in a show of solidarity with Palestinians suffering amidst the ongoing conflict with Israel. Alam, who also sits on the board of advisors for Artists at Risk Connection, continues his activism and art-based advocacy, lending his support to pro-democratic efforts in Bangladesh and beyond.