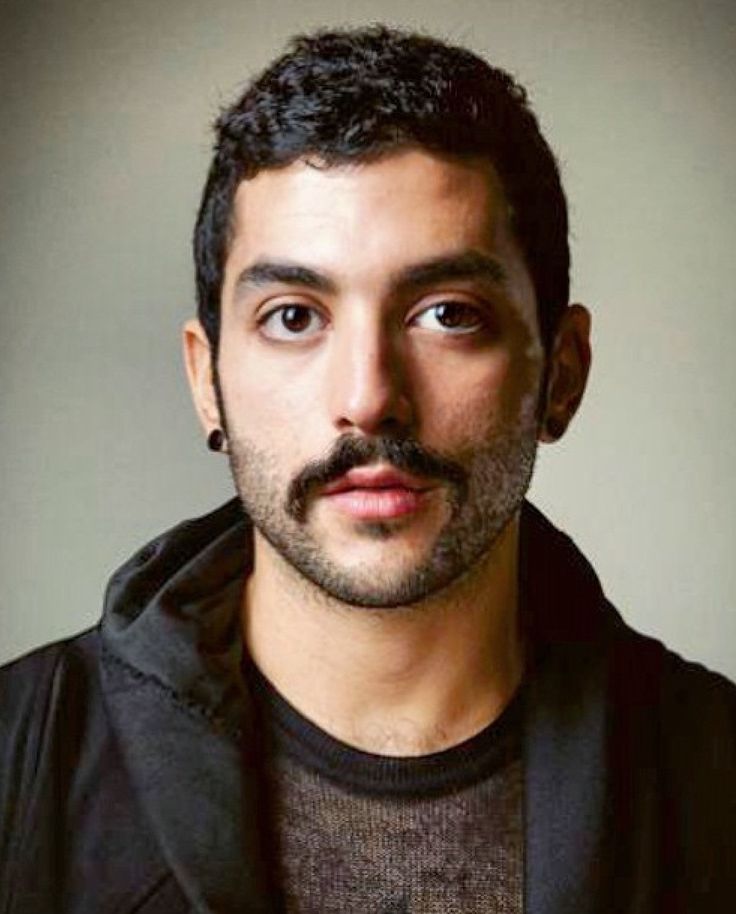

Hamed Sinno

Musician

Lebanon

Hamed Sinno has amassed a huge following in his home country as the lead singer and co-founder of Mashrou’ Leila, one of the biggest bands in Lebanon. Hamed proudly embraces his queer identity and is an LGBTQIA+ advocate in both his songs and his life. As a result, he has faced years of backlash and harassment. The hate campaign reached a boiling point in August 2019, when organizers of the Byblos International Festival, one of the country’s biggest music events, where Mashrou’ Leila were slated to play, received death threats and were accused of blasphemy due to Hamed’s lyrics and social media posts. Hamed now lives in the United States.

I was always someone who, by Lebanese standards, was not very gender conforming. I quickly started finding myself in music, and the anxiety that I felt about constantly being bullied, of constantly feeling like I was outside—music was the thing that would keep me off the ledge.

I feel like it’s impossible for music to not be political because at this point it’s impossible for anything to not be political. You’re always consenting to or dissenting from the status quo, and it’s impossible to escape that power structure. If you’re not using the medium and your platform to address that power structure, then you’re basically consenting to that structure and the way power is distributed, the way capital operates, the way audience expectations inform the kind of music that gets produced.

From the beginning, the harassment started immediately. My studio space in college would get vandalized by people spraying slurs about my sexuality on my equipment or on my artwork or on the walls. There was a lot of intimidation in the press from the get-go, people using tropes that have been historically used against the queer community in Lebanon. For example, in Lebanon and other places in the Arab world, people asking for LGBT rights have long been labeled as “agents of Western imperialism,” as if non-heterosexuality was invented in the West.

I remember one incident in Tunis where we had to hire a security team. The band was starting to get bigger, and we were starting to get into weird, uncomfortable situations with some of the fans, and the harassment from people who were bothered by the band was starting to get a little more intense. And when the security team found out I was not straight, they also started threatening us, which was funny.

I never felt entitled to ask other artists for support. I always felt almost embarrassed. When support came, if it came, that was great, but it rarely came from other artists in the region. The music scene is very masculine and very male driven, so there’s been a lot of homophobia, a lot of resentment that the band was doing so well. So I never really felt like we had allies in the Arab music scene outside of Lebanon.

In Lebanon we got a lot of assistance from various human rights organizations and from the arts community. Honestly, what happened was very special: They organized a concert when ours got canceled, so there were all these bands that came out and played to support our band. There were all these actors and visual artists and musicians and theater people who came together, and it stopped being just about the band—it became about freedom of speech, and that was really beautiful to see.