Badiucao

Cartoonist

China

UPDATE: On September 17, 2020, Budiucao was named a recipient of the 2020 Václav Havel International Prize for Creative Dissent.

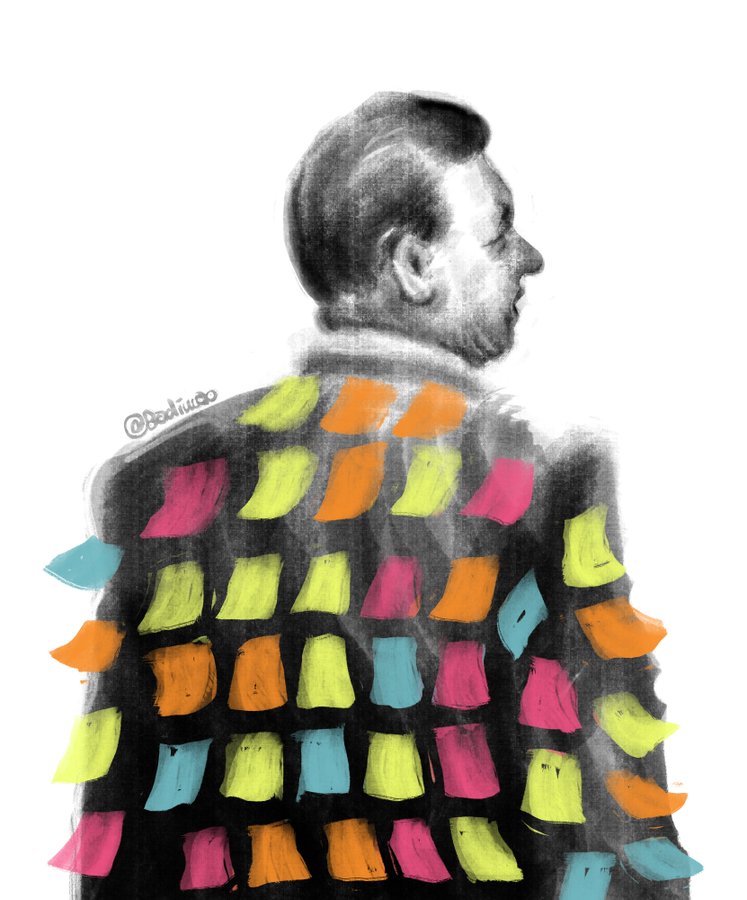

Badiucao's design for a report on the Chinese government's social media activity.

The Party enforces this intolerance for dissidence through its strict control of the internet, rationalized through the concept of “cyber sovereignty.” In an age when internet exposure is a necessary building block in the careers of artists—and when social media platforms serve as outlets for artists and activists—artists living under censorship are left with limited choices, often having to “take one’s chances in speaking freely, self-censor, withdraw from the conversation, or leave the country.” If they do choose to take their chances, the consequences can be serious: prominent Chinese political artists like Ai Weiwei and Wu Yuren have been repeatedly arrested and harassed for their work and for their outspoken reformist views.

Badiucao’s 2017 portrait of Liu Xiaobo.

Badiucao’s cartoon for the “Lennon Wall” in Hong Kong during the 2019 protests.

Badiucao chafes at the label “cartoonist” as opposed to “artist,” saying, “I feel the art world does not embrace political art properly. The world sees me as a political cartoonist, but [for me] political cartoon[ing] is simply the most efficient way to spread my art.” Even if he started as a cartoon artist, Badiucao’s output has expanded in recent years to include public installation art. Much of his recent work, especially pieces created in connection with human rights campaigns or protests, encourages opinionated participation from his viewers. During the Hong Kong anti-government protests, Badiucao provided a print-able template for a “Lennon Wall,” a participatory public work of government critique.

Badicuao's depiction of the infamous St. Louis couple seen pointing guns at peaceful #BlackLivesMatter protestors in June 2020.

Badiucao created his art under a pseudonym for years out of fear for his family’s safety in China, even after he moved to Australia in 2009. On the thirtieth anniversary of the Tiananmen Square massacre, Badiucao was forced to unmask himself. A new documentary about his art, called “China’s Artful Dissident,” had just come out, and he was preparing for a show in China honoring the late Chinese political prisoner Liu Xiaobo. It quickly became clear that Chinese authorities did, in fact, know his identity, especially once his family in China was detained by the police. Badiucao called off the show and revealed his identity from Australia.

“Artwork is purely non-violent,” Badiucao has said. “It’s just a message. Any rational government should not be afraid of it.” Of course, the Chinese government is afraid of the power of dissident artists like Badiucao. He has had to cut all ties with his family in China for their safety and was forced to pull out of another group show about the Hong Kong protests in Australia after a curator became fearful of Chinese backlash. And yet, he has vowed to keep creating, to continue fighting for freedom and human rights in China with the only weapons he wields: his pen and his creative voice.

By Annie Kiyonaga, July 2020. Annie is a recent graduate from University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, where she studied art history and literature. She currently lives in New York, where she’s working for an education non-profit.