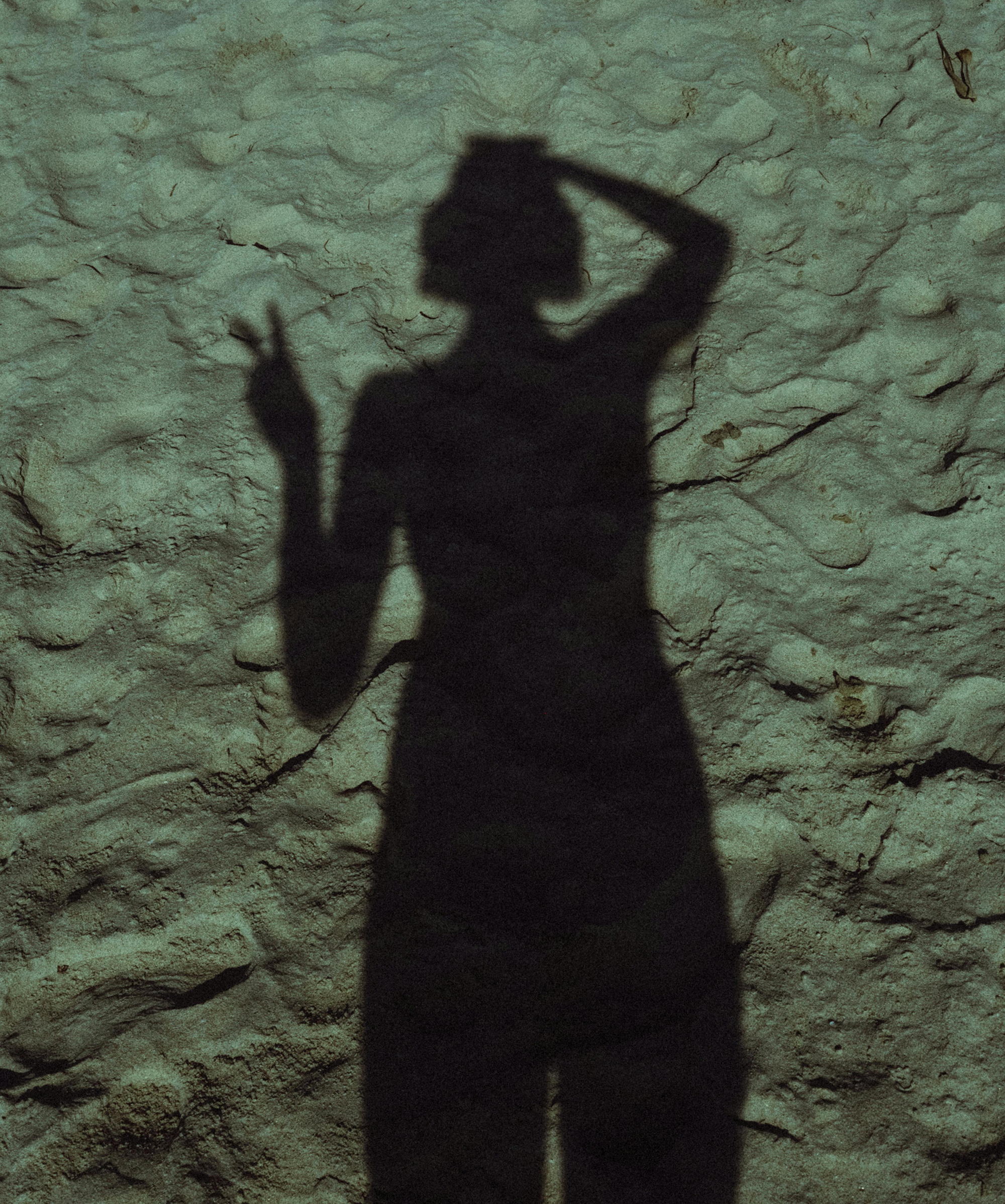

Kseniya B

Filmmaker

Russia

As a gay artist raising her son alone, she faces the challenges imposed by the political climate in Russia, where the LGBTQ+ movement has been labeled as extremist. Laws prohibit the “propaganda of so-called non-traditional values,” putting individuals like Kseniya B at risk.

Many members of the LGBTQ+ community find themselves in similar perilous situations, and thousands have faced repercussions due to their sexual orientation.

“Any wrong step I take and my son will go back to an orphanage.”

– Kseniya B

ARC Interview with Kseniya B

Why did you agree to speak only under a pseudonym while living in France?

I would love for someone to come and dispel my fears by saying, “Oh, come on, who would want you?” But the Russian authorities have long reach. We are in France on humanitarian visas; it’s not political asylum, but visas that the Atelier des artistes helped us obtain. We were among the last to manage that, as they no longer assist with such visas. So, I still don’t feel protected; I fear that my son might be checked.

We visited Russia before moving to France—to visit my mother and gather our belongings. On our way out, while flying to Almaty instead of France (there are no more direct flights), the authorities at passport control demanded documents a court ruling on the adoption.

Was that illegal? What did you do?

Of course, it was illegal; they had no right to ask for such a document. But who would I prove that to when they could simply deny me entry? I bought the ticket with my last money.

I have an adopted child who is 11 years old. The guardianship authorities, who are supposed to check on us, still call me. When the war began, my son was on a guest arrangement—living in an orphanage while coming to stay with me on weekends and holidays. I realized that I needed to act quickly, but my goal was to help him adapt to a home and family life. It was very turbulent and challenging; we struggled to find a psychologist willing to help us. My child came from an orphanage—he didn’t know how to read, didn’t know the days of the week, wasn’t even aware of his own birthday; these were the consequences of hospitalism. He was under tremendous stress.

Those were the most difficult months—while the war was already underway, we still couldn’t leave. It was incredibly tough; I felt like I was going to lose my mind.

We left so that he could talk about everything. One of the most frightening moments during that time was when my son and I were riding the metro in Moscow. At one point, the train stopped, the doors opened, and a squad of soldiers entered. The doors closed, and my son asked, “Mom, are those people going to kill Ukrainians?”

If you stay silent, stay home, and don’t go out, you could probably somehow continue living.

My last project as an artist in Russia was a Gaidan performance, where musicians took turns blowing out candles and leaving the stage until no one was left. I created video art for this performance, which consisted entirely of footage that was circulating on social media at the time—explosions, artillery shells. Public screenings were banned immediately, but they showed it in a closed setting. However, I realized that I couldn’t sign it with my name; I hadn’t participated in protests or anti-war actions. I understood that any misstep on my part could lead to my son going back to an orphanage.

If they come in to reach out, they will reach out. I lie to them that we are in Kazakhstan; I can’t say we are in so-called an unfriendly country. I started preparing a plan, and when the mobilization began, I got scared that the borders would close for everyone—I grabbed my child, the cat, bought tickets, and we went to Kazakhstan.

To what extent did your queerness influence your decision to leave? How did you feel in Russia as a representative of the LGBTQ+ community?

Since I had a child, my personal life has gone deeply underground, and I cleaned up my social media very thoroughly. I didn’t meet anyone and didn’t tell anyone anything. While we are citizens only of Russia, I don’t tell my son that I am gay.

LGBTQ+ people in Russia have become accustomed to living underground, saying nothing to anyone, always staying silent. We don’t know any other way of life; for us, it is normal. This has been a deeply ingrained pattern since childhood, that you shouldn’t talk about it with anyone. When I interacted with the guardianship authority, I even had to adjust my appearance a bit. Because of this, I wanted to leave long before the war; that’s why I am speaking under a pseudonym now. I saved money, gathered documents to have a child. I didn’t think it would happen so quickly. I managed to have a child, but I didn’t save enough money—when we left, we had $1000.

Many Russian artists we work with have experienced two waves of emigration over the past 2-3 years: first to a visa-free country, and then to Europe. Can you talk about this experience?

I have a kid and a cat. This complicates things a lot in terms of housing. If it were just me, I would rent a room without a worry. But with a child and a cat, we need to live separately. I’m currently working just for housing. As soon as we arrived in Kazakhstan, I grabbed my backpack and started working as a deliverer. I worked as a courier for three months, then began working in a theater and taking side jobs. I developed my course for set designers—using video in performances. I managed to save some money; my son got used to it a bit. Here in France, I borrowed money, which allowed me to not work for an entire month. During that month, I learned the language. Moving to France was much more complicated—I was going to nowhere. I had no one here, no friends, no connections. I had been to Paris once before. I traveled thinking: what am I doing? What am I doing? It was clear this was a one-way trip. Looking back, it’s terrifying to think about how I could have dared to do this.

What helped you or could help you remain an artist? How do you maintain your profession in exile?

Sometimes it seems to me that I haven’t preserved anything; I’m in a state of deep exhaustion. I’m addressing only my need for food and a roof over my head. I clean garbage bins and hallways in five buildings. It feels a bit like a Dostoevsky novel. I’m constantly sick and coughing because I have to wash the bins with icy water. Of course, I plan to do some art project with these bins. Otherwise, one could just go crazy. My mind still works as an artist; I look at the world around me and think: when all of this is over, when there’s time, I’ll create an awesome video art piece. But for now, nothing has come to an end.