Artist Profile

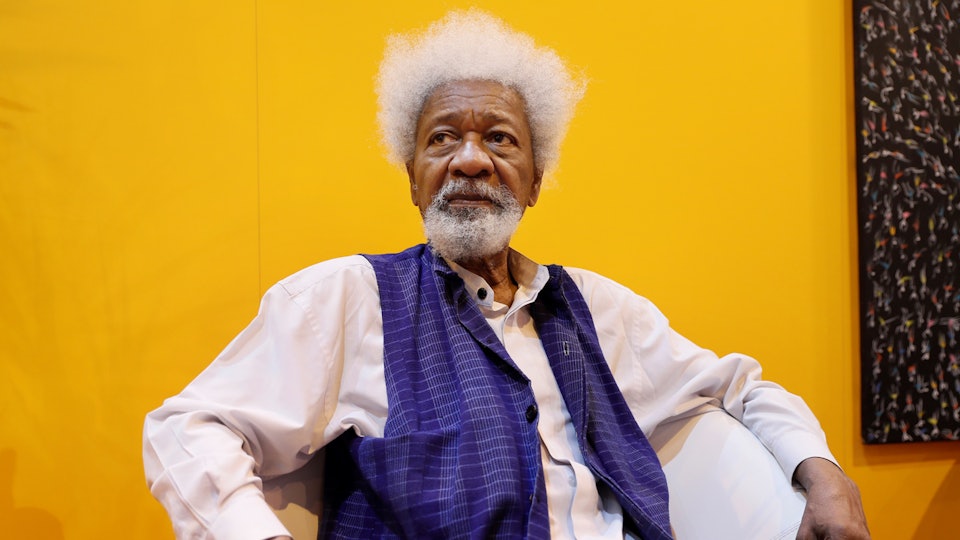

Wole Soyinka

The Universality of Human Rights and Cultural Rights

On October 23, ARC participated in a panel in conjunction with the session of Third Committee of the United Nations General Assembly entitled “The Universality of Human Rights, Cultural Diversity and Cultural Rights: A Cultural Rights Celebration of the 70th Anniversary of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.” The panel included UN Special Rapporteur Karima Bennoune, Director of the Due Diligence Project Zarizana Abdul Aziz, and Nigerian writer and Nobel laureate Wole Soyinka.

Soyinka delivered a moving speech in which he argued for a renewed proactive commitment to upholding human rights. Culture, he suggests, must necessarily be built around an inherent core of human dignity.

ARC reproduce a transcript of the speech below both to commemorate the 70th Anniversary of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and to affirm its continued importance as we seek to address social and cultural struggles of the present and future.

Good evening and thank you all for taking time to be here. I have two narratives, both taken from Nigeria where I live, where I was born, and a land of many cultures. The first narrative: In most societies, we know that traditional rulers are the recognized custodians of culture. That’s why they’re called traditional rulers. One of the most influential, important in Nigeria, is the Obi of Onitsha whose name is Achebe. In Onitsha is an important city among the Igbo people, and the Igbo people have a tradition called Osu. Once you know about the untouchables in India, you understand what Osu is all about. The most degraded kind of socially regarded people—as far as I’m concerned not just in Nigeria, but on the entire African continent. It’s not just that they are the untouchables and that the most menial and disgusting social label is assigned to the Osu. Once you are born into the Osu class, you are there. Your children and children’s children remain Osu, untouchable for the rest of their lives. And if you marry into an Osu family, your children become Osu and of course, you become pariahs in society. As always, from within the Igbo people themselves and within Nigeria, there has been a campaign against this degradation of humanity and the preservation of this class called the Osu. And recently the Obi of Onitsha, the custodian of Igbo culture, added his voice, his very powerful voice, on the side of the eradication of this so-called culture among the Igbo, which reminds us that culture is not static.

Here is another narrative: We had a governor in Nigeria who later became a legislator, and he had a very remarkable taste for underage women. In fact, not just underage, but the children of a particular nationality or race. In Egypt, he began importing underage children for marriage in Nigeria. Now the laws of Nigeria are quite clear. The age for marriage is there on the statute books and the constitution. The laws of Egypt equally frown on underage marriage and copulation with underage children. So we have this governor breaking the laws of two nations on two criminal accounts, one pedophilia, and two cross-border sex trafficking. However, he resorted to the argument of cultural relativism, said “No, this is my culture. I am a Muslim; Islam permits me to copulate with underage children. What the Quran does not forbid the constitution cannot forbid. To each his own culture.” Later on, he even became a legislator, in other words, a maker and guardian of the law, which he had already sworn to break even before he became a legislator. There was an uproar all over Nigeria. In the media he was attacked even by his own fellow Muslims, and by female jurists, one of them on the Supreme Court, who was able to counter him with a chapter and verse in the Quran—because he kept citing the prophet Mohammed as his authority, that Mohammed married an underage child—and he was challenged by his own fellow Muslims that although Mohammed may have been betrothed to her, there is no evidence that he actually consummated the marriage at that tender age. But no matter what anyone said, he got away, literally, with murder. He was a serial predator who married them at 11, divorced them as tradition allowed him at about 14, and had them replaced. I think he must have had a contract for a regular supply of victims. However, just like among the Igbo people, one of the most powerful voices and defenders of Islam in the country, the Emir of Kano Lamido Sanusi, added his voice against the practice of underage marriage. Not only that, he set an example by trying to lift women up from second- and third-class citizenship by assigning his daughters to special positions in the social and sometimes governance aspects of his emirate.

So there we are. We have two narratives, both of them citing maleficent aspects of culture. And here within in those same cultures we have voices raised against an unacceptable “cultural practice.” See, those who talk about culture are sometimes very selective. These are the ones in fact who are against the cultural plurality principle, the manifestation of culture in all its forms, because they deny other people their own interpretation of their own cultural basis of existence. As I said earlier this morning, from within the corpus of traditional law, various rituals, performances, even chapters and verses of the scriptures, some of which in fact are in print, we find if not exact wording, the equivalent of the principles which are outlined in this manifesto known as Universal Declaration of Human Rights. So the argument that this is a Western concept, and that Western culture can now dictate Western culture, Asian culture, African culture is not dictating to any other culture. It is simply identifying certain principles which elevate humanity rather than degrade humanity or sections of humanity. But you may ask me, “Well, how do you make a choice? Are you on the side of Emir of Kano? On the side of—what’s his name again? I so despise him I never can even dare to pronounce his name, the governor, legislator who indulges in cross-border pedophilia and cross-border sex trafficking—you’ve got to choose. We’ve got to choose. Are you on the side of the Obi of Onishta? Or the other throwbacks of society who insist that the practice of Osu must go on and that no descendant of Osu should even aspire to either a political or social respectable level in society? So how do we choose? How do we tell those on the other side how we choose, what parameters we use?”

Why don’t we remind them of what age we live in, what is happening in other fields of society? Forget culture, forget human rights; what’s happening in other fields of human endeavor? I think it was not so long ago that Japan collaborated with European nations to send a rocket into space on a seven-year journey to Neptune. Before that I believe there was the lander called Philae, which docked together with a comet streaking across the sky. That was just about 5 years ago, I believe. I think we have a responsibility to ask those on the other side, what age do they live in? Ask them, do they live in that age when at the sight of a moon eclipse their forefathers would have brought out tin cans and drums to chase away the devils which were supposed to be eating the face of the moon? Do we ask them, truly ask them, what they want? Is it that age, perhaps, when there was an eclipse of the sun you had to sacrifice seven virgins or seventy virgins to appease the demons blocking the sun from giving light to this world? There are choices to be made even outside the parameters of what we call strict culture. There is the fact that human society, humanity, does not stand still. And if humanity doesn’t stand still in one area of creativity, why should it be static in other areas such as the treatment, the consideration, and the valuation of human beings?

The document known as the Universal Declaration of Human Rights takes into consideration, as incidentally the mythologies of many societies, what exactly is a human being. What is a human being? What does he or she consist of? We know what the deductions of most these progressive mythologies are: that the human being is not relative. That there cannot be one rule for one section of humanity as for the other. And those who flouted this basic principle, this imperative of human existence, have come to very bad ends in both folklore and mythology. And I think we need to teach that, to preach that, repeat it especially to young people so that they can have a response when they an, “Ah, yes, yes, yes, you are brainwashed, you’ve become Westernized, and that’s why you are spouting all these rights and so on.” No, ask those people who insist that their culture forbids freedom of speech, for instance, what they are using to communicate with. Is it not also the faculty of speech? In other words, all they do is collect, amass the rights which belong to the totality, for themselves. Again, we are back on this principle of power and freedom, the axis on which history itself swivels from time to time.

When I was coming here this evening, because I think we were very concerned, more concerned in fact with action than with a repetitive regurgitation of same principles year after year, seventy years after the declaration. We contend with what exactly we do; where do we go from here? As I came-in I was reminded of my last visit. I think it was this very building. It wasn’t this room; it was another floor somewhere. And it was specially selected. It overlooked the flags of the United Nations. We had a beautiful picture of that event. What were we doing there? We were placing President Omar al-Bashir on trial. Who assisted? The organizations who flew in reporters, journalists who had witnessed atrocities committed by this regime. We flew in survivors, women especially, some of them victims of rape, who came and testified for two days. And of course, Omar al-Bashir was invited to appear. We knew he wasn’t going to, and we sent invitations to his embassy, and, the end of course we appointed lawyers to represent him so that a fair trial actually took place, against the background of United Nations flags. In the end, he was found guilty, predictably. The evidence was overwhelming.

I think perhaps it is time we structure trials like that. I look at a character like Jammeh, for instance, of the Gambia, one of the worst criminals against humanity ever produced by the African continent. He comes very close to Idi Amin and all those monsters, Mobutu Sese Seko and company. Now, he’s being ousted, finally ousted by his peers, by the Gambian people themselves upon the election, which he refused to acknowledge until African leaders had a meeting with him and told him, “It’s time to go for you.” Well, he left. But there is no accountability for his crimes. He is enjoying himself as a guest of yet another petty dictator on the West African continent. He has looted that country. He left with fleets of and cars, gold, etc., etc. He is having a wonderful time. , And the results of those trials should be sent to various governments, so they are not at liberty to roam around the world, enjoying the proceeds of terror against their citizens. I think events like that should become standard so that they do not believe, having got away literally with murder, they are free to enjoy the rest of their lives while others remain permanently traumatized.

An organization to which I belong will be mounting a worldwide reading. People reading on behalf of persecuted and endangered writers, some of them in prison. In this particular instance it has been decided on December 10, there will be a worldwide reading in the memory of the murdered journalist Khashoggi. This will take place simultaneously on December 10 at a time to be decided. I think that the UN should also participate in events like that. Such descendant should also take place in front of the embassies, the embassy involved in this unspeakable crime against the right of free speech. There are many other possibilities of galvanizing public opinion so that we do not lament after the event, and we put all other dictators and torturers on notice that when it is possible to exact reckoning from you, it will happen, sooner or later. It would put governments on notice and embarrass them, making sure that this kind of reading takes place in front of the Saudi Arabian embassy in the United States and everywhere if possible.

We need proactivity. We need to use a different language from what we are using right now. Not academic language; it is very useful tool, we know, we in the academic world—that’s our trade. But we are talking about real life, what actually affects people, how they are affected, and how this is perpetuated. We need a different language of address, not the anodyne language of infractions and “lack of observance” of human rights. No, we are talking about the language which terrorists deserve, the language which reflects what they have actually done to other human beings. We need to pose the question to ourselves, to our children: Decide. Choose. What age do you live in? Do you live in age of cowering the moment you see an eclipse, or the moment when you take out your iPod and you communicate with the next person and say, “Don’t miss that streak that across the sky. It’s going to happen in few days.” We have to keep up the humanist aspect of the scientific and technological advances that this world has already achieved.

In the words of the late Secretary-General of the UN Kofi Annan when he took office—remember his words—he said this century would be marked by the attention and its commitment to the sacrosanctity and dignity of human existence. These were the words of Kofi Annan when he took office. I think we owe not just to Kofi Annan but to the predecessors in the struggle for human dignity and fulfillment, to bear those words in mind and really dedicate what’s left of this century to enabling the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and carrying it to the point where the document is no longer needed. Thank you very much.