Artist Profile

Gaudêncio Fidelis

Brazil

Status: In Exile

Gaudêncio Fidelis was born in February 1965 in Gravatai, a district in the southern state of Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil. From a young age, he showed a strong interest in art, eventually leading him to earn a B.A. in Fine Arts at the Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul, and later, M.A. in Art from New York University (NYU), and a PhD in Art History from the State University of New York (SUNY). He has since become a preeminent curator and art historian with a long career in and out of museums and cultural institutions in Brazil and elsewhere. Among other roles, Fidelis has worked as the director of the State Institute of Visual Arts of Rio Grande do Sul (IEAVI since 2011) and was the founder and first director of the Museum of Contemporary Art of Rio Grande do Sul (MACRS). He has also curated more than fifty exhibitions at esteemed institutions around Brazil. However, as nationalist fervor has swept through Brazilian politics in recent years and fomented increased violations of freedom of expression and hostility toward the LGBTQI+ community, Fidelis found his curatorial work caught in the crossfire.

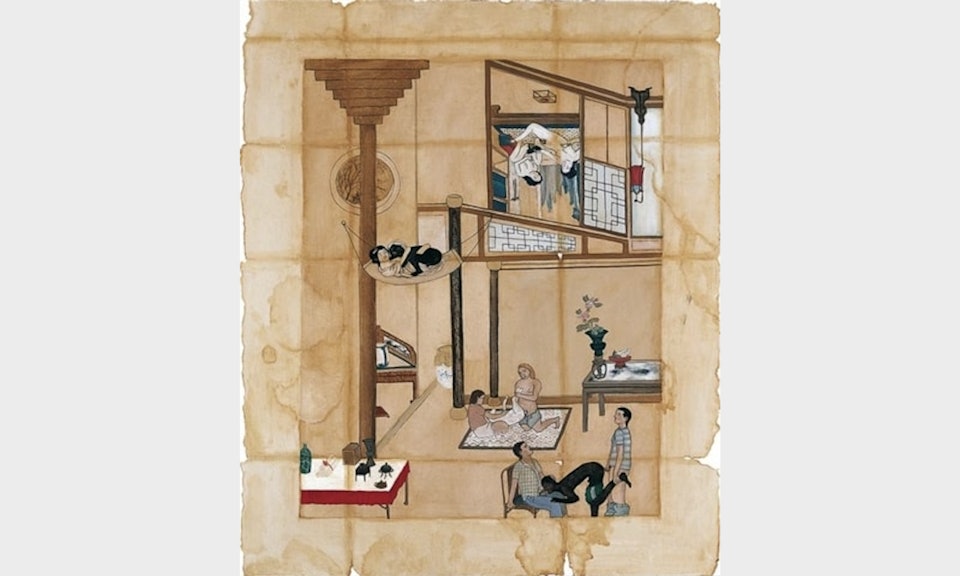

In 2017, when Fidelis inaugurated Brazil’s largest-ever queer art exhibition

The situation escalated with

However, the MBL’s toxic narrative about Queermuseu quickly ramified through social media. By decontextualizing and circulating select artworks from the exhibition alongside fake news, far-right critics were able to incite moral outrage around the country. Queer Child by Bia Leite, a series of portraits of children with words like “transvestite” and “gay child” stenciled across them, was particularly targeted. The work explores the reality of growing up queer, and the violence of being labeled and demeaned through language.

Under pressure from far-right groups, religious zealots including Pentecostal and Neopentescostal Evangelicals, and negative media coverage, Santander (which one of the largest banks in Brazil and was the exhibition’s funding institution) made the unilateral decision to close Queermuseu and released an ambiguous condemnation statement.

In the wake of the show’s closure, Fidelis suffered continuous death threats by religious and right-wing groups, indefensible congressional investigations, and public denunciations. Many now view Queermuseu’s closure as a turning point in recent Brazilian history. Since then, a generalized crackdown on freedom of expression and democracy has permeated Brazilian society, especially after Jair Bolsonaro’s right-wing regime came into power in January 2019. Bolsonaro’s cabinet has systematically undermined democratic, cultural, scientific, and educational institutions in the country, as well as censored or attacked the press, exhibitions, plays, books, artists, teachers, and minority and LGBTQI+ groups. In fact, when Bolsonaro was federal deputy for Rio de Janeiro, he applauded the closure of Queermuseu and said that the “author of that exhibition”–– i.e., Fidelis –– should be killed.

In spite of the threats against Fidelis, he has never given up the fight against censorship and the struggle to communicate the truth about Queermuseu and his curatorial work. Alarmed by the country’s increasingly nationalistic policies, Fidelis even decided to bring that fight to the government itself, running for federal deputy of the Brazilian Workers’ Party in 2018. Alongside Fidelis’s efforts, more than 2,800 newspaper articles were published globally about the exhibition’s closure, bringing international attention and outcries from around the world in support of artistic freedom and queer art. Many cultural organizations expressed their support for Fidelis, inviting him to re-open Queermuseu at a different venue. With the help of the Parque Lage School of Visual Arts, in Rio de Janeiro, he managed to set up one of the most successful crowdfunding campaigns ever launched in Brazil and reopened the exhibition in August 2018. More than 10,000 people attended the inauguration.

However, Fidelis continued to feel unsafe in his homeland, and was often unable to go outside or travel in public spaces. He decided to apply to the Scholar Rescue Fund (SRF), a program that helps threatened scholars around the world. The SRF ultimately led him to The New School’s New University in Exile (UIE) Consortium, where he now works as a research scholar in the field of Art History. He arrived safely in New York City in October 2019.

ARC is proud to have supported Fidelis's application to continue pursuing his critical curatorial and scholarly work. Besides connecting him to resources when he was at risk, ARC also invited Fidelis to participate in a two-day workshop on Art, Activism, and Human Rights organized with the Center for Legal and Social Studies (CELS) in Buenos Aires in October 2018. This event brought together artists, academics, lawyers, NGO representatives, and more from across Latin America for an engaged discussion on the state of artistic freedom and human rights in the region. We look forward to our ongoing relationship and collaboration with Fidelis and are eager to see what work he has in store in New York.

By Alessandro Zagato, March 2020. Alessandro is ARC's Regional Representative for Latin America.