Podcast

¡El Arte no Calla! - Episode 10: Political Cartooning and the Venezuelan Diaspora with Rayma Suprani

"¡El Arte no Calla!,” a new monthly Spanish-language podcast of the Artists at Risk Connection (ARC), explores art, freedom of expression, and human rights in Latin America. In each episode, ARC's Latin America Representative Alessandro Zagato will invite a different guest to help analyze the varying states of artistic freedom in Latin America and the violations that artists and activists are suffering in the region.

Episode 10: Political Cartooning and the Venezuelan Diaspora with Rayma Suprani

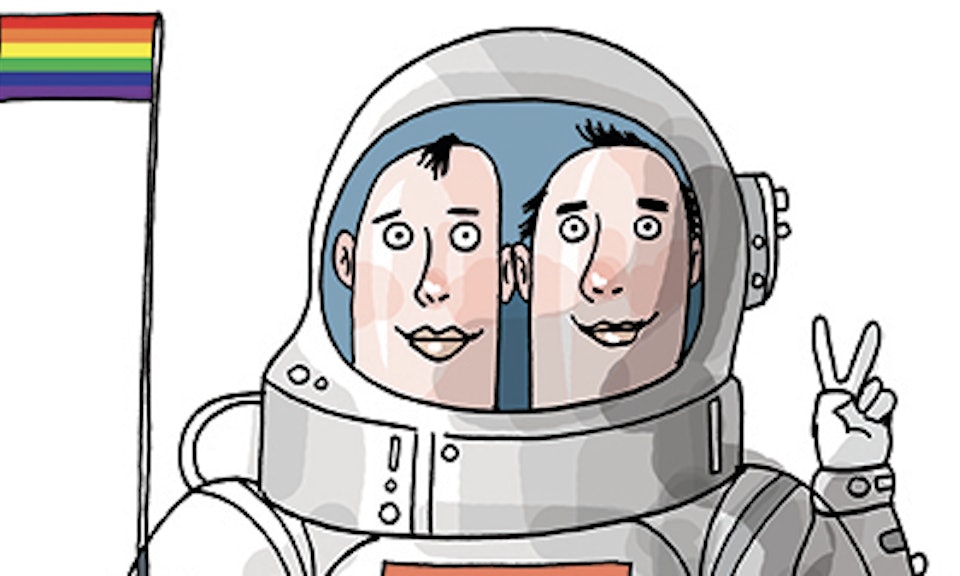

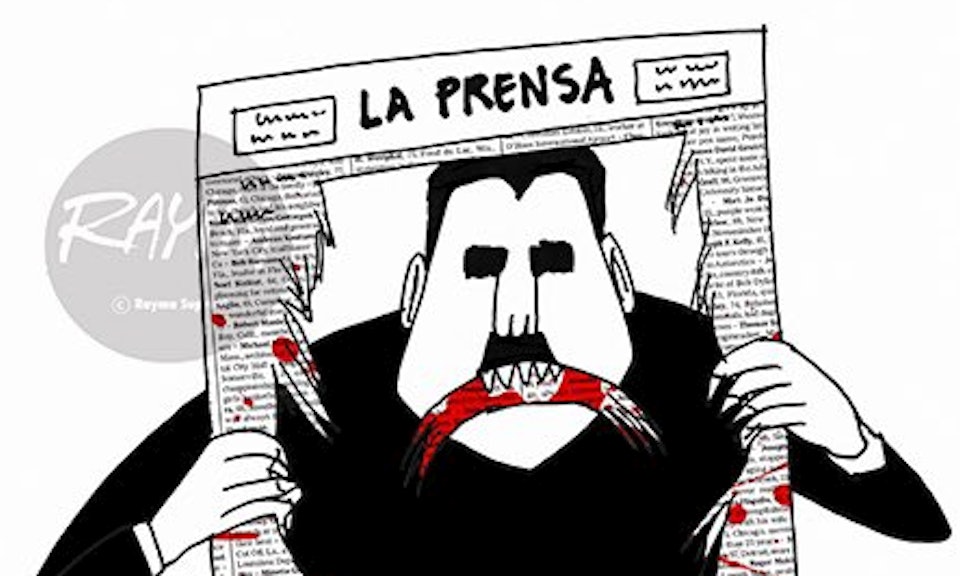

In this episode of ¡El Arte no Calla!, ARC sits down with Rayma Suprani, a prominent Venezuelan cartoonist who worked for twenty years at the national tabloid El Universal but had to leave her country after being persecuted and threatened for her satirical work. Rayma reflects on the important role of political cartooning, a form of art that challenges power and dominant perceptions and allows people to see things from a different, often provocative point of view. She also considers the worrying human rights situation currently shaping Latin America and Venezuela.

Alessandro Zagato: Can you tell us about your artistic and journalistic trajectory?

Reyma Suprani: I studied journalism with a focus on graphic journalism, and I have many years of experience at several Venezuelan outlets. My last experience at El Universal was definitely the largest, as I worked there for approximately twenty years as the author of the daily editorial cartoons. This was such an important experience for me because it matured alongside intense political and social transformations in my country. Within those conflicts, political cartooning played a prominent role of denunciation and confrontation at multiple levels. It also helped people understand what was going on at that time in Venezuela.

A.Z.: Do you consider political cartooning only as a space of denunciation, or is it also a form of art? Do you consider yourself an artist?

R.S.: My work was always related to social and political themes because it was always displayed in the press. Today everything has changed because I do not work for a specific journal, and the media are also changing because of the power of the internet and social networks. An evolution is underway where eventually paper will be completely substituted by screens. My production was tied to the harshness of the political conflict – which is, by the way, typical of many Latin American countries shaped by crises and corruption. However, at the same time I also do artistic work, which I perceive as more gentle and noble, and which is not as known as my work of political denunciation.

“I believe that cartooning is an exercise of free thinking – it constitutes an important indicator of freedom in a country – and we can express this freedom on a daily basis through our creativity.”

A.Z.: For its critical and thought-provoking nature, political and satirical cartooning is usually subject to hostility and attacks. This is also part of your experience. Could you tell us why you had to leave Venezuela and move to the United States?

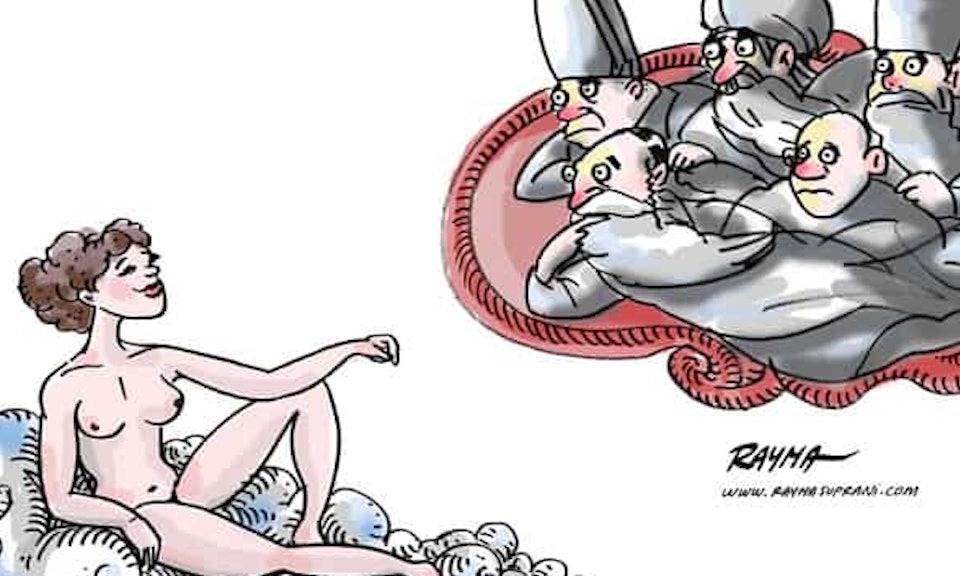

R.S.: When I started working at El Universal it was also the beginning of the government of Hugo Chavez, which was democratically elected but it concretely behaved as a military dictatorship. Afterwards it was succeeded by Nicholas Maduro and is still a tyranny of corruption and drug trafficking. This situation has had the effect of suffocating the media. For example, just some days ago the headquarters of El Nacional, a journal that was one of the bastions of free press in Venezuela, was seized by the military. All this reduced the possibility of working with freedom of expression in Venezuela. I was heavily persecuted and even received death threats, and six years ago I had to leave; I live now in the United States, a freer and safer place where I can keep working and express my opinions on my country’s political situation. I believe that cartooning is an exercise of free thinking – it constitutes an important indicator of freedom in a country – and we can express this freedom on a daily basis through our creativity. Obviously, this is not easy work, because several times even cartoonists can have their own taboos or ambiguities, but hopefully we can overthrow those walls and keep doing our work. For instance, I was educated as a Catholic person, but in my career I have done several draws denouncing the shortcomings of the Catholic Church, such as cases of child abuse and so on. Our work allows us to highlight topics that are uncomfortable or taboo in society.

“I had never thought or wanted to leave my country. I was forced to do so because I was experiencing a situation of threat and risk.”

A.Z.: Could you tell us about how the process of leaving your country and moving to the United States has been?

R.S.: In fairness, I had never thought or wanted to leave my country. I was forced to do so because I was experiencing a situation of threat and risk. The Venezuelan diaspora grows every day, there are approximately six million Venezuelan people currently living outside the country. These are huge numbers, but the people who like me had a public type of work had to leave faster and without any other option. The city of Miami, where I live, has a broad Latin culture, and there are many migrants who arrived here escaping from political and economic conflicts, so there is a very plural idea of freedom towards Latin America. On the other hand, I had the luck of finding a space that is relatively close to Venezuela and where I am able to keep doing my artistic work of denunciation and keep expressing my opinions on the lack of human rights and justice in my country.

A.Z.: Your drawings do not just refer to Venezuela, they also describe other contexts in Latin America and the world. What do you think about the human rights situation in the region?

R.S.: I think that problems have become bigger in the world, including the lack of human rights, and Latin America is not an exception. Situations like those lived, for example, between Israel and Palestine, or the processes of migration from Africa to the European coasts of the Mediterranean sea, where people dramatically die, are important references for cartoonists who are willing to highlight and denounce injustice. We seem to live in an eternal conflict. We are currently trying to overcome a pandemic – that somehow gave us a time to reflect on ourselves and the lives we live – and we came back to a state of war. There are places like Venezuela where the vaccine is not available for a big part of the population, or you have to be a member of the party to get it. These are very sad topics, but drawing and cartooning can be an important exercise in the construction of historical memory.