Podcast

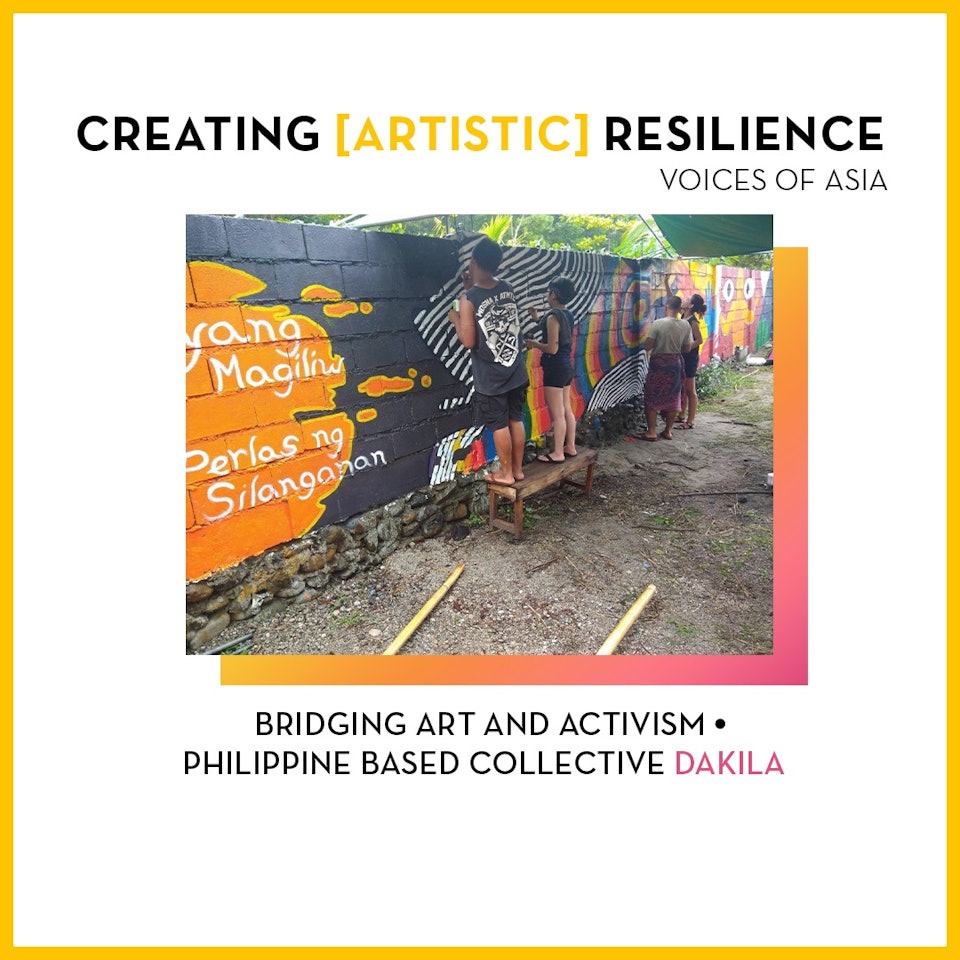

DAKILA on Bridging Art and Activism

Creating Artistic Resilience: Voices of Asia

Listen to Leni Velasco and Andrei Venal, members of the Philippine-based art collective DAKILA and the Active Vista Centre, share their insights on censorship, red-tagging, and digital activism in the Philippines. The duo also discuss the significance of art-based human rights interventions in the sociopolitical narrative of their country and the role of art in catalyzing change in civil society.

This episode is from the limited run podcast Creating Artistic Resilience: Voices of Asia brought to you by ARC, in partnership with the Mekong Cultural Hub and FORUM-ASIA. Throughout this series, ARC’s Asia Regional Representative, Manojna Yeluri, will speak with artists and cultural rights defenders about their experiences engaging with artistic freedom in their countries.

MANOJNA – Welcome guys, thank you so much for joining us today. Could you begin with helping us understand the current state of freedom of expression and human rights protection and advocacy in the Philippines today? It's a very broad question, but I think it would be great to help set the tone and context of the conversation.

ANDREI – We are living in what we are calling two kinds of pandemic here in the Philippines – the first one is the COVID-19 pandemic, which hampered a lot of the ways we are moving and interacting with the world, so everyone has turned their lives a full 180 degrees, with a lot of change in terms of that. We are currently far from going through this pandemic again. Nothing good is in sight with the current state of our health protocols and the lack of vaccines, especially in the rural areas here, and in the urban areas as well, especially in the areas of the poor.

And the other pandemic is authoritarianism, which also hampers a lot of the good work that we are doing. It's pretty hard having those two challenges that are facing us today. It's hard to move around, it's hard to interact with many people, and to an extent it's being weaponized by the state and it's creating this crisis into a state weapon to further suppress and strip us of our human rights.

LENI – What Andrei is saying refers to the whole idea that there's actually two viruses being spread here in the Philippines. It's not just the COVID-19 pandemic, but the whole virus of having human rights being demonized and portrayed as if it's something that you need to give up for you to survive in this pandemic. That's how the whole pandemic context works here in the Philippines.

MANOJNA – How does DAKILA fit into responding to all of this? Maybe you could tell us about DAKILA itself and about the kind of work that you engage in?

LENI – DAKILA is an artist activist collective, so most of our members are from the creative industries and mostly artists. What we've been working on is how art, media, and popular culture help in our social advocacy and that’s what we've been doing in the past years. It’s especially at these times, when we are under an authoritarian, populist government that the role of artists as changemakers is especially in demand.

Here in the Philippines, the way things are framed is that we are at war. When the current president took over, the first “war” he initiated was the war against drugs. Then there's the “war” against the opposition, or what we call the Yellow people or the “Dilaw.” And then there’s the “war” against activists and human rights defenders, so since our current president took over, it’s like we're on a warpath. There’s this whole narrative that there's a war going on – whether it's the war against the drug users or the war against activists, even in other pandemic contexts, where the virus is like something that you can shoot to kill.

ANDREI – Aside from DAKILA being a collective of artist-activists and being potent actors in this change-making scenario that we are in, I think DAKILA is more than a political platform. It’s also a space for innovations and so this is a very fertile space, like a laboratory on how we can make change-making irresistible to our audiences and we can develop new ways in educating people on human rights issues and promoting democracy. And so, aside from being an organization of artists, DAKILA is a space as well. Before the pandemic, it was a physical space for people to meet and share ideas on how to address things. It was a visual space, a network of thoughts and ideas on trying to figure out how we can be better at the human rights work that we do.

“ It's not just the COVID-19 pandemic, but the whole virus of having human rights being demonized and portrayed as if it's something that you need to give up for you to survive in this pandemic. ”

MANOJNA – You mentioned that DAKILA almost serves as a laboratory for innovation – would you and Leni mind sharing a few projects that have been incubated at DAKILA? Especially now, with the pandemic, there is a shrinkage of spaces, so how does all of this tie in together and what are some of the ways in which DAKILA has been proactively helping?

LENI – DAKILA has run the ACTIVE VISTA Human Rights Film Festival since 2008. It's our seventh or eight edition this year, so the human rights film festival has evolved into not just a film festival, but really into a media, arts, and creative festival where it's a space to promote human rights. That's one of the first innovations that we started in DAKILA and how to marry our art with our activism through this festival.

We have a lot of creatives in our network – musicians, filmmakers, poets and writers all working together with the civil society organizations, hearing different opinions for this festival, either through film screenings or exhibitions or websites that focus on some of our themes. I think Andrei can talk about our martiallaw.ph which came out of the lab projects that we've done in the past year.

ANDREI – With the martial law cities here in the Philippines, there was a question of how to share the learnings from that year with the younger people right now, because currently there's a lot of historical revisionism. I don't know, nor can I say, who are the proponents of that revisionism but our question was, how do we bridge the learnings of the past with the children of the future? So we tried to develop this digital space – it's a digital museum, called the “Digital Museum of Martial Law in the Philippines” – the URL is http://martiallaw.ph and we tried to create digital exhibits there with poetry, with animation, with interactive timelines, which tells people that these things have happened in the past and these are the stories that have been passed, so we tried to get a bit more creative in the dissemination of this information through that digital museum.

I think it's a good way to bridge the distance between cruelties here in the Philippines. We are an archipelago and one just simply cannot go to Manila to visit the Marshall Museum. We needed for this to be online and that's a good example of the innovation that we do.

LENI – At the heart of it, what we've been trying to do, why innovation and creativity are so important to us, it’s to make this information more relatable, specifically to the general public and the younger generation because we feel that through creativity or through the arts for example, in this lobbying kit that Andrei had mentioned (offline), instead of a whole document, which is the way to lobby – you give documents to legislators, but we had musicians coming up with songs about climate change or disasters, we had spoken word artists talking about climate, we had visual artists making comics – so it's more relatable to most rather than bombard them with jargon and technical language. Which I think is important because our role as communicators is to make this more understandable to the common person.

“there's a lot of historical revisionism. I don't know, nor can I say, who are the proponents of that revisionism but our question was, how do we bridge the learnings of the past with the children of the future? ”

MANOJNA – Do you find that your projects and interventions of this kind receive sufficient funding and support from local authorities and local institutions in the Philippines?

LENI – In the past, it has been a struggle. Normally, you wouldn’t get funding for artistic events or more creative projects like these. We usually find funding like this thanks to donors abroad, but most recently because of the human rights situation and the whole context in the Philippines where everyone is trying to reach out to the general public to make things more understandable and relatable. There's a lot of misinformation and fake news going on – more institutions have been looking at artists and creative groups like ours, to help bridge that gap. Compared to past years, there's more support in terms of that, but then another challenge is that the civics spaces we're in are always challenged or corrected.

MANOJNA – It’s reassuring to know that artists and the creative community is being encouraged to engage more deeply with these issues of social justice. On the flip side, do you feel that the creative community is also becoming more vulnerable to harassment and threats and attacks?

Could you maybe speak to that a little bit especially in the context of the Philippines and the work that you're doing?

LENI – We have a member who was threatened and harassed legally, and detained for making a Facebook post criticizing the government in a very satirical manner on how they were handling the whole public health crisis. She said that her city was at the center of the pandemic universe and then she was detained and arrested in the middle of the night, because of her satirical post. It was a big case during the lockdown last year, when she was very much in the middle of the whole politics of the local government of her city. She was awarded by an international group, for a freedom of expression award, right after she was arrested. She's a known filmmaker and lives in our city.

ANDREI – These are grassroots people, but artist celebrities have been under attack as well. There are several celebrities here in the Philippines, very popular people who have expressed their dissent and some opinions on how the country has been handling the pandemic, and then they were criticized and scrutinized by the government. No one is safe from the attacks both physically and in terms of wellbeing.

LENI – The film community is really vocal here in the Philippines, and even before the pandemic, have been active in resistance to human rights violations.

Two years ago, the military in the Philippines red-tagged or accused filmmakers and some schools of recruiting communists through the film screenings that we have been doing. And we at DAKILA have been very active in schools showing films, complemented with forums on human rights issues. The film community banded together and made a statement against all the threats of the military and red-tagging they’ve been making against the filmmakers and film screenings and the schools that have been doing the film screenings. That's how bad it is, and it's linked to this fictional plan. The military said that there is this plan to overthrow the government, and that the screenings were being used to recruit activists or communists to help this coup attempt.

ANDREI – It’s quite absurd. But this is how this all relates to artists and groups like DAKILA because if you're branded as a proponent of insurgency and that affects the way you get funded, it affects your organizing work and nobody wants to be connected with you.

LENI – And people are getting scared. We used to partner with a lot of schools, but because of this military, press statements and targeting filmmakers organizing screenings, schools are afraid to even show these films.

MANOJNA – It’s incredibly depressing to actually see this trend and this idea that there's so much anxiety now around artists and artistic freedom. I think it's a huge source of of growing anxiety especially amongst those of us who engage deeply with creative mediums as forms of advocacy

If you're not directly censoring, by removing support, would you say that this is a way to curb artistic freedom or freedom of speech and expression?

ANDREI – It is, actually. When you say shrinking civic spaces, we’re not just talking about the physical spaces where people can protest with their artworks, but also the non-physical spaces of networking and alliances that are being cut off from you when oppressive entities start attacking you. If you take a step back and look at the kinds of attacks on artistic freedom, it’s very big and wide and takes on different forms.

“When you say shrinking civic spaces, we’re not just talking about the physical spaces where people can protest with their artworks, but also the non-physical spaces of networking and alliances that are being cut off from you when oppressive entities start attacking you.”

MANOJNA – I am very curious to know more about DAKILA’s work in digital activism and the work that needs to be done with respect to digital harassment and risks that cultural rights defenders are facing in the digital space – is that something that the two of you could speak to?

ANDREI – Leni can go into the details of this, but I would like to share the general concept of digital activism. So when we say digital activism, it's not just an alternative to the physical activism or on-ground real life activism that we do. It’s treating that as a blended space where all your work and learnings exist in both on-ground realm and digital realm as well. When we talk about campaigning, we’re also talking about digital campaigns working hand in hand with the ground work that we do, as well as digital security. We need to empower the activist-artist with security both on ground and in digital spaces. When we say digital activism in DAKILA, it’s a very holistic view of art activism work related to human rights across the digital landscape and the physical landscape.

LENI– When human rights organizations talk about digital activism, it tends to focus on digital security only, but we’ve been advocating that digital activism shouldn’t be defense only, in terms of your fear protection. We should be proactive in really organizing an army of human rights advocates online. Here in the Philippines, the phenomenon of trolls really contributes to the silencing of people or civil societies from speaking up and expressing their opinions and views. As civil society organizations, we should be also actively challenging this kind of behaviour and culture online. So what we teach in digital activism is that we should also be actively organizing human rights activism online to counter misinformation, and to educate what human rights is even in digital spaces. It’s very important to not be silenced online, and to organize our own advocates in the digital space so we can challenge these troll armies that are paid to demonize and silence us.

ANDREI – You empower the artists more, and to mitigate the risk when you allow them to move in different spaces as well, so that’s one of the points of the digital activism programs in DAKILA – to mitigate the risks by allowing them to practice their work in spaces that are less hazardous to their life, livelihood and lifestyle.

LENI – That’s also the framework of how we do our narrative change approach. We have explored three approaches to really challenge our current situation. With authoritarianism going on, we are using creative resistance. Part of resisting creatively is not just about being resonant with our creative messages in terms of your advocacies. Creativity should be a form of your protection, because when you present your resistance more creatively, it becomes like a Trojan horse.

“Creativity should be a form of your protection, because when you present your resistance more creatively, it becomes like a Trojan horse.”

MANOJNA – Would this extend to situations where when you say creatively resisting, it’s literally being creative in the ways you communicate creativity and dissent -- so almost subverting, but still in a way that isn’t very direct or in your face?

LENI – To last in the struggle in the Philippines, you have to be really creative. For instance, the lessons that we learned during martial law in the Philippines, we had artists who tried to put their works of resistance in mainstream publications so that you can get the subliminal message of it. They would still be able to protect themselves and their jobs in a mainstream publication, newspaper, or lifestyle magazine, but are able to really put out their message in a creative way.

MANOJNA – To me this embodies the way forward, and is almost a moment of hope which, of course, we all need. Because things seem rather dreary. But would you say overall, that artistic freedom is at a tipping point in Asia? It’s a big question, but how do you feel about it?

LENI – Definitely. There’s a global solidarity movement because of what happened to our colleagues at the Freedom Film Festival in Malaysia, where Anna Hor, the festival director and animator, has been questioned by the police because of the short film that they made and published. And this is just one of the things that has been happening across Asia. One of our colleagues in the Human Rights Festival network was arrested during the military takeover in Myanmar. Artists are actually easier targets because their creative works are out there.

MANOJNA – What would you say is the kind of support that the international community and other civil society organizations can offer organizations engaged in work that DAKILA is engaged in or to artists who are very proactively putting themselves in situations of risk? What can we ask the international community to help us with now?

ANDREI – It’s hard because in our region, the ASEAN region, there’s so much diversity, both politically and culturally, which also serves as an opportunity for more solidarity work, international work or work for democratic movements. I can’t exactly pinpoint those, but at the end of the day, support the livelihood of artists and cultural workers – that’s one way of ensuring that the work they do continues, and to provide a space of protection and security for them by adopting them as cultural workers into the fold of some bigger organisations, that can provide some security to these people. And to continue to work with them to create lasting cultural changes because they are the main force in bringing about change culturally.

LENI – What the creative sector needs right now is protection of their rights. They need to have a network of like-minded individuals, such as artists like themselves who have spaces for conversations, to share their own insights, tips, and guidelines to better protect themselves. Last year we started a series of digital security trainings, especially in the social media influencer community of the Twitter, Facebook and Instagram world. How can they better protect themselves and protect their digital selves? I think it’s really eye-opening for these artists, because they’re rarely conscious of these things, but they did appreciate how digital security can really affect their lives, especially in the context of really high risk situations, like being tagged as opposition or an activist in the context of human rights in the Philippines.

Second, there are more ways now where artists can actually collaborate with each other, seeing as how they’re all mostly online now and there’s restrictions on how we can connect together, explore how collaborations can help each other, both for the country specific work that we do and then how this can contribute to more democratic spaces and alleviate the human rights situation in the region.

MANOJNA – I think everything that you shared right now is a starting point for so many other organizations and stakeholders. I would really like to thank the both of you for taking time out and sharing space with us, answering all these questions and helping us gain a better insight into the kind of work that you’re doing and what’s happening in the Philippines. Thank you so much for your time.

ANDREI & LENI – Thank you so much too!

MANOJNA – On behalf of everyone in the creative community, we’re so happy to know that a space like DAKILA exists. To many of us, DAKILA is less of an organization and more of a symbol of collective action. So I think it’s incredibly motivating and inspiring to hear about the kind of work that you’re doing and we stand in solidarity with everything that you’re doing. Thank you so much.

LENI – Manu, I think it’s important to note that as artists and creatives we really make it a point not to forget to have fun in the things that we do.

ANDREI – What’s the point of revolution if we cannot dance?

To learn more about DAKILA and stay engaged with their activism, check out their website and follow them on social media: