Artist Profile

Badiucao

China

Status: In Exile

UPDATE: In February 2022, Badiucao's Beijing 2022 Olympic posters were at the center of a censorship scandal at The George Washington University. Members of the student body protested the display of Badiucao's works around campus. The posters criticized the Chinese government's surveillance policies, lack of transparency surrounding the COVID-19 pandemic, persecution of Tibetans, genocide against the Uyghur population, and dismantling of Hong Kong's democracy. GWU President Mark Wrighton, replying to initial student outcry, stated he was "personally offended" by the images and immediately acquiesced to demands for their removal, without any consideration of freedom of expression. Badiucao, along with other GWU students and members of the public, condemned President Wrighton's decision as censorship. President Wrighton later apologized in a statement to the GWU community, noting that he made a mistake and that he recognized the arts as a "valued way to communicate on important societal issues." This incident marks just one of numerous successful and attempted efforts to censor Badiucao's work within the past year.

UPDATE: On September 17, 2020, Budiucao was named a recipient of the 2020 Václav Havel International Prize for Creative Dissent.

Chinese dissident artist Badiucao can trace his political awakening back to a single work of activism: a VHS tape, dissected and spliced by local activists to include graphic footage of the 1989 Tiananmen Massacre. Badiucao was in university at the time, where he and some friends had rented a rom-com on VHS. Information about the Tiananmen Massacre is heavily censored in China, and Badiucao was shocked by the footage. He recalls thinking, “If I can’t see the truth about the country, how can I have hope for the country?”

One form of truth, at least—the truth about artists under China’s authoritarian rule—could be found within Badiucao’s own family. Badiucao is the latest in a long line of persecuted artists: his grandfather and great uncle, both filmmakers, were killed during Mao Zedong’s persecution of intellectuals. Mao’s Cultural Revolution brought about a new, harsher era of repression in the long, complex history of Chinese censorship, particularly in regard to artists and intellectuals. Under Mao, art that was not explicitly propagandistic was banned, and many artists—like Badiucao’s family members—were killed for their “bourgeois,” Western influences. This legacy of government censorship can be seen today in the ruling Communist Party’s attempts to curb Western influences in its insular art world and its swift crackdowns on artists thought to criticize the Chinese government.

The Party enforces this intolerance for dissidence through its strict control of the internet, rationalized through the concept of “cyber sovereignty.” In an age when internet exposure is a necessary building block in the careers of artists—and when social media platforms serve as outlets for artists and activists—artists living under censorship are left with limited choices, often having to “take one’s chances in speaking freely, self-censor, withdraw from the conversation, or leave the country.” If they do choose to take their chances, the consequences can be serious: prominent Chinese political artists like Ai Weiwei and Wu Yuren have been repeatedly arrested and harassed for their work and for their outspoken reformist views.

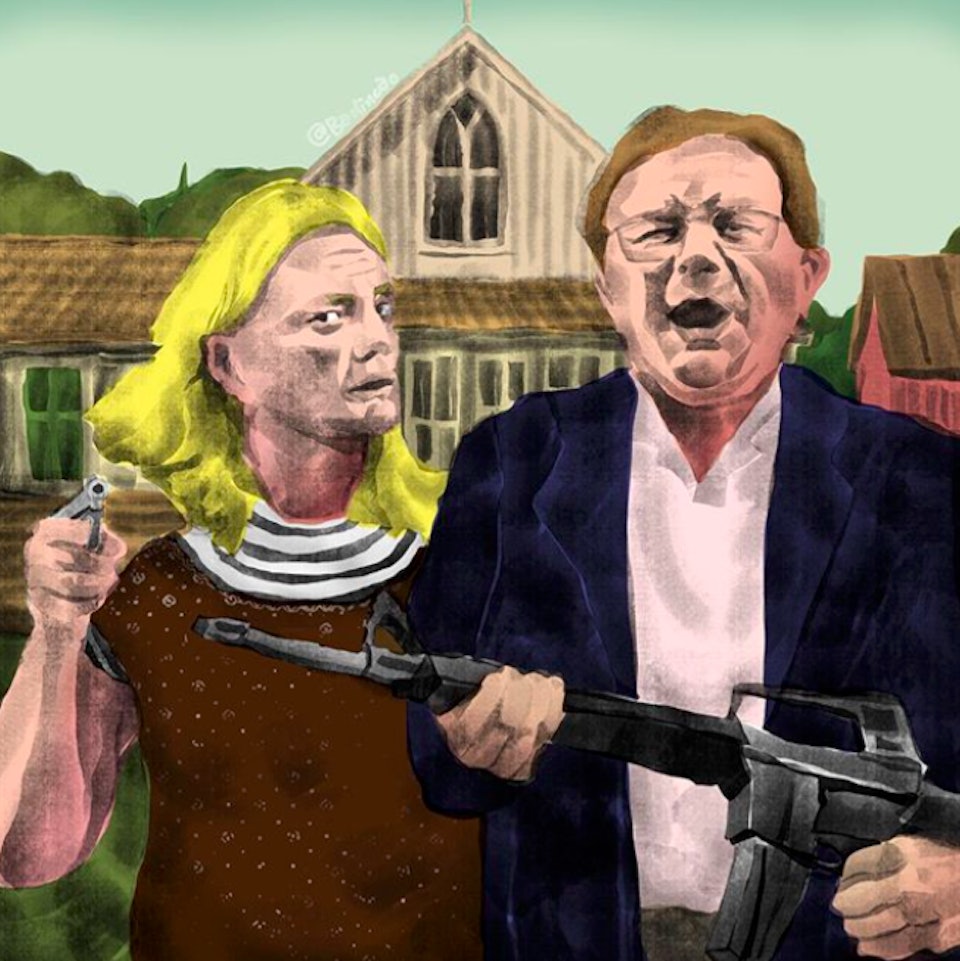

Despite this harrowing history, Badiucao felt compelled to start drawing satirical political cartoons after his exposure to the Tianenman footage. His early works established his vibrant and expressionistic trademark style, characterized by bold black lines and irreverent, graphic images. Chinese president Xi Jinping appears often, as do scores of Chinese dissidents and intellectuals. Badiucao’s drawings of Chinese officials like Xi Jinping are darkly comical, earnestly critiquing human rights abuses and censorship while maintaining a guise of slapstick mockery: a “Keep calm and fuck human rights” slogan with a Queen-Elizabeth-inspired portrait of Jinping comes to mind. By contrast, his portraits of activists, intellectuals, and dissidents feel meticulously affectionate. One particularly poignant example was a 2017 portrait of Liu Xiaobo, the late Chinese Nobel Peace Prize laureate and writer who was jailed by the Chinese government for his political activism, embracing his wife, Liu Xia.

This dichotomy of satirization and commemoration remains a constant theme throughout Badiucao’s work. His cartoons are often weaponized as funny, sharply angry commentary against Party leaders, but can just as easily serve as thoughtful, warm memorials to Chinese agitators and thinkers. Interestingly, Badiucao’s drawing style itself seems to shift as he roams between these modes of depiction. His satirical drawings of politicians rely on emotive, dynamic black lines and intense colors, while his portraits of dissidents are carefully crosshatched, rendered with delicate, realistic lines and softer coloring.

Badiucao chafes at the label “cartoonist” as opposed to “artist,” saying, “I feel the art world does not embrace political art properly. The world sees me as a political cartoonist, but [for me] political cartoon[ing] is simply the most efficient way to spread my art.” Even if he started as a cartoon artist, Badiucao’s output has expanded in recent years to include public installation art. Much of his recent work, especially pieces created in connection with human rights campaigns or protests, encourages opinionated participation from his viewers. During the Hong Kong anti-government protests, Badiucao provided a print-able template for a “Lennon Wall,” a participatory public work of government critique.

Badiucao created his art under a pseudonym for years out of fear for his family’s safety in China, even after he moved to Australia in 2009. On the thirtieth anniversary of the Tiananmen Square massacre, Badiucao was forced to unmask himself. A new documentary about his art, called “China’s Artful Dissident,” had just come out, and he was preparing for a show in China honoring the late Chinese political prisoner Liu Xiaobo. It quickly became clear that Chinese authorities did, in fact, know his identity, especially once his family in China was detained by the police. Badiucao called off the show and revealed his identity from Australia.

“Artwork is purely non-violent,” Badiucao has said. “It’s just a message. Any rational government should not be afraid of it.” Of course, the Chinese government is afraid of the power of dissident artists like Badiucao. He has had to cut all ties with his family in China for their safety and was forced to pull out of another group show about the Hong Kong protests in Australia after a curator became fearful of Chinese backlash. And yet, he has vowed to keep creating, to continue fighting for freedom and human rights in China with the only weapons he wields: his pen and his creative voice.

By Annie Kiyonaga, July 2020. Annie is a recent graduate from University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, where she studied art history and literature. She currently lives in New York, where she’s working for an education non-profit.