Artist Profile

Ai Weiwei

China

Status: Under surveillance, In exile

Ai Weiwei is a child of dissidence. Born into a family of activists, Ai Weiwei spent his youth first in a labour camp in Beidahuang, Heilongjiang, then in exile in Shihezi, Xinjiang. It’s no surprise that his work is so deeply political and critical of the Chinese state. Whether he is covering the floor of the Tate Modern in the United Kingdom with 150 tons of porcelain sunflower seeds or photographing himself flipping-off Mao’s mural on the walls of the Forbidden City, Ai’s work has drawn intense criticism from China’s communist party.

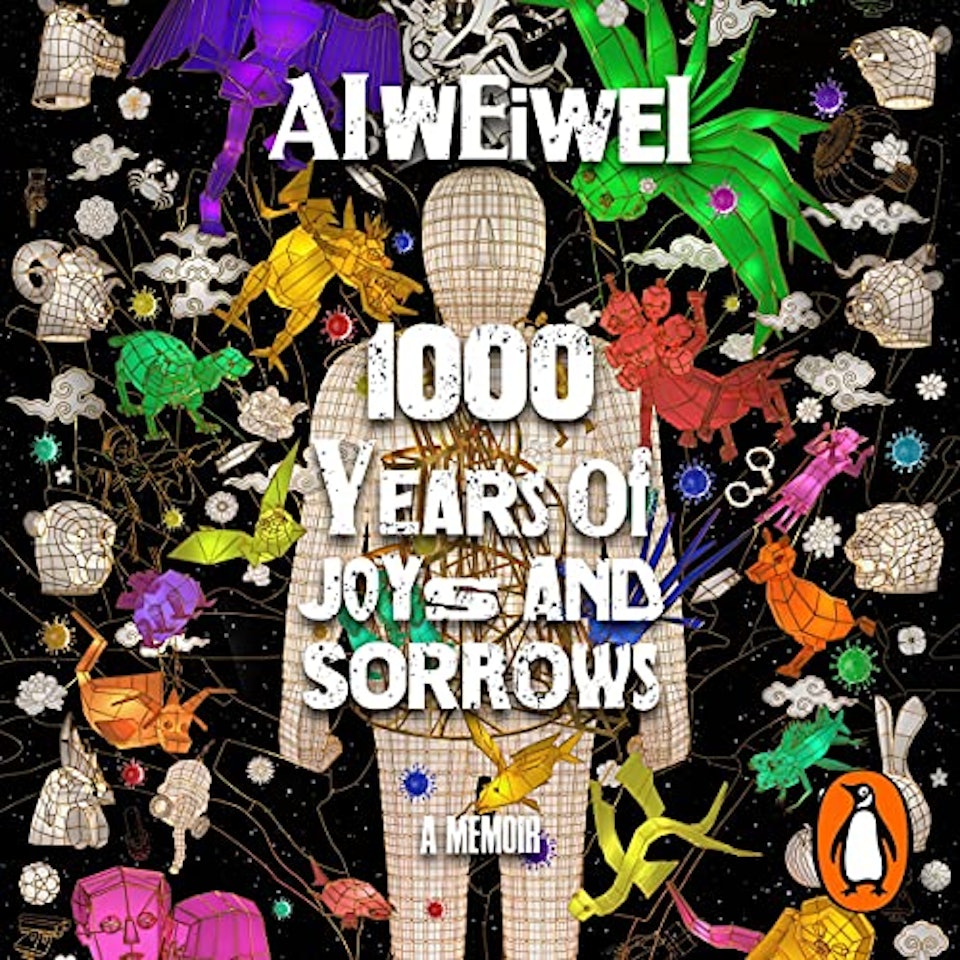

Ai has earned international acclaim for his art and activism, becoming one of the most recognizable artists in the world. In his highly-anticipated memoir, 1000 Years of Joys and Sorrows: A Memoir, released on November 2nd, Ai tells the story of the last century in Chinese history by chronicling his own extraordinary life as well as the legacy of his father.

Through his creative work, Ai is known for calling attention to government corruption and providing chilling commentary on pressing social and political issues. Following the devastating 2008 Sichuan earthquake, which cost the lives of 69,000 people, Ai launched a “citizens investigation” with writer Tan Zuoren. The two believed corrupt government officials were cutting corners by constructing structurally unsound buildings known as “tofu-dreg” projects in reference to the crumbly, brittle pieces left over after making tofu. When an earthquake hit Sichuan, one of these buildings, a schoolhouse, collapsed in a tragedy that cost the lives of over 5,000 students. Haunted by the images of the scattered backpacks and school supplies left in the wake of the disaster and few remnants of their lives left after the disaster, and disgusted by the Chinese state’s all too familiar response of censorship to the tragedy, Ai refused to let the voices of victims' loved ones go unheard. Ai used 9,000 blue, red, yellow, and green backpacks to cover the facade of the Haus der Kunst art museum in Munich, Germany in commemoration of the victims of the quake in 2009.

After the tragedy, Chinese social media rapidly became a hub of investigation for the public seeking transparency and accountability for the victims. A citizen investigation team, born out of Ai’s call to action, became instrumental in gathering information on the lost children. As the truth was laid bare, public outcry intensified. The informal investigation continued for nearly a year, until the Chinese authorities eventually shut the blog down after repeated attempts to detain members of the team, destroy materials, and prevent further dissemination of information.

Before dedicating his blog to investigating the earthquake, Ai used his online platform to voice sharp criticisms of the state. The blog’s shut down in 2009 was a pivotal moment in Ai’s fight against censorship. Turning to Twitter and other platforms, he embarked on a new and dangerous path as he continued to pursue the truth in the face of state power.

In 2010, Tan Zuoren, Ai’s partner in investigating the tofu-dreg projects was arrested and put on trial on charges of “subverting state power.” Ai Weiwei attempted to testify at his friend’s trial, but was beaten fiercely by state officials. After complaints of head pain, it was discovered that Ai had a cerebral hemorrhage. The trauma of the assault was so severe that Ai would have to undergo emergency brain surgery for wounds that would take years to heal.

Ai’s interactions with the state would only continue to escalate over the years and in 2010, after hearing his newly built studio in Shanghai would be demolished by the local government, Ai planned to throw a party on the site in protest. State police then put him under house arrest to prevent the event. Needless to say, the party was held despite his absence, but the studio was demolished the following year.

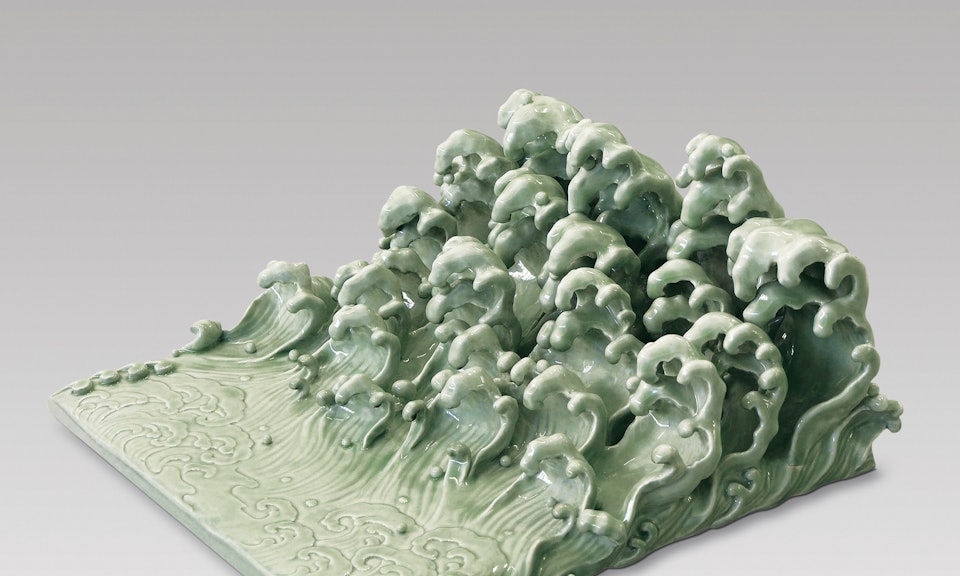

Ai’s pursuit of the truth has assumed the form of documentaries, visual art installations, social media campaigns, performance art, and other mediums. Across these art forms, Ai’s ability to visualize and portray the tension between the past and the present remains his most powerful commentary. For Ai, this tension often manifests in physical objects as he manipulates historical objects or raw materials in sometimes shocking ways. Ai’s destruction of a Han Dynasty Urn in 1995 is one of his most well-known pieces. For the piece, he uses historical objects to comment on his “reverence for the past and the irrepressible drive towards the future,” while invoking complex socio-political commentary on the Chinese state. Although many were outraged by this work, calling it an act of desecration, Ai defended his piece by referring to the state-sanctioned destruction of antiquities during China’s Cultural Revolution (1966–76) to pave the way to the creation of a new future.

Ai’s first brush with the Chinese state dates back to his early years. His parents, poet Ai Qing and writer Gao Ying, were no strangers to political persecution. During the Anti-Rightist Movement, his father was accused of “rightism,” and the family was exiled for twenty years in the province of Xinjiang. In the foreword of his novel Yours Truly, Ai recounts his family’s forced displacement, his father’s imprisonment, and the suffocating isolation he and his family endured. After years of being subjugated to the harshest of conditions in the remote province, Ai and his family returned to Beijing in 1976 shortly after Mao Zedong’s death.

In 1989, Chinese civil society was forever altered when students gathered in Beijing's Tiananmen Square on June 4, calling for greater democracy, freedom of the press, and freedom of speech. As crowds of almost a million thronged the square troops armed with assault rifles fired at the demonstrators killing hundreds and injuring thousands more. News of the Tiananmen Square Massacre sent shockwaves through the world and fear of further violent military action smothered almost all civil disobedience. Artists, creatives, and other revolutionaries were, however, undeterred, going underground and forming a movement. This community of dissidents became a home for Ai Weiwei upon his return to China from the United States in 1993, where he studied for two years with a handful of other Chinese students.

Since the tragedy at Tiananmen Square, Ai has produced numerous works criticizing the Chinese authoritarian state and has solidified his position as one of the most influential and controversial figures in China. Looking at some of his most well-known pieces including Study of Perspectiven, Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn, Sunflower Seeds, and, of course, Remembering, Ai’s commitment to social justice is clear. The underlying theme of a need for transparency also emanates from each of his pieces and underlines Ai’s belief that “if a nation cannot face its past, it has no future.”

Despite his international acclaim, Ai remains a target of the Chinese Commuist Party’s harassment. While traveling to Hong Kong in 2011, Ai was detained by Chinese authorities at the Beijing airport on unfounded accusations of tax evasion. Labeled as a “deviant” and a “plagiarist” by Chinese state media, Ai’s arrest sent a message to the international community: nobody is “untouchable or off limits'' to the Chinese authoritarian regime, no matter how well-known. For nearly three months, individuals, organizations and governments around the world protested the unlawful detainment. He was eventually released on bail after a period of 81 days, during which time he endured what his sister described as psychological torture. Under constant surveillance in a continually lit cell, two guards stood close to Ai at all times, watching him even as he slept. Still, even after his release, Ai was not permitted to leave his home in Beijing for another year, and his passport was only returned four years later.

In 2014, Ai created an exhibition based on his reflections on incarceration, entitled @Large: Ai Weiwei on Alcatraz. In addition to filling the notorious California prison’s halls with brightly colored dragons and other traditional Chinese imagery, the artists encouraged individuals to send “postcards to prisoners of conscience around the world [...] to let them know they [were] not forgotten.”

Today, Ai Weiwei remains exiled in Europe with his son and partner. His work continues to be widely exhibited across the world with “Trace,” an assemblage of eighty-three portraits made entirely of thousands of LEGO® bricks, most recently on view at the The Skirball Cultural Center in New York City.

By Ben Ballard and Tenzin Tsephell Choegyal.